A random remark to a group of school mums eventually led to Elaine Miller donning a vulva suit in the Scottish parliament.

Miller told the politicians she knew how to “make their willies stronger for longer”. More of that later.

Her journey to the vulva suit began several years before while chatting with the school mums about turning 40. The conversation turned to their “bucket list”. One wanted a divorce, another intended to run a marathon, a third said she would finish her degree.

Miller said she would perform a stand-up routine. “It was all I could come up with,” she recalls.

She followed through. An Edinburgh resident, she took part in the annual Edinburgh Festival Fringe, telling a true story about a disastrous family picnic.

The audience roared. “I really, really enjoyed it,” she recalls. “And I noticed on stage that as long as you can make it funny, you can get away with any social taboo; it doesn’t matter how dire.”

A specialist in pelvic floor issues

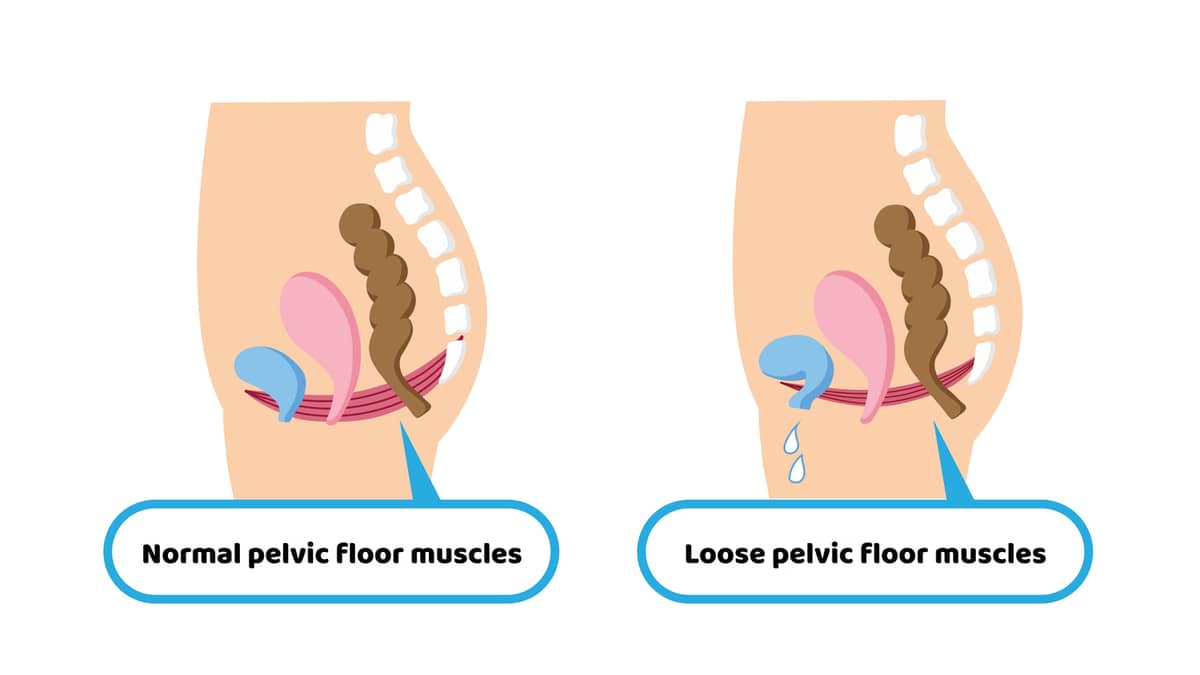

For her day job, Miller is a physiotherapist specialising in the pelvic floor. It’s little-known that many distressing and common health issues – incontinence and failure to orgasm in women; premature ejaculation and erectile dysfunction in men – can be reversed by simple pelvic floor exercises.

“So I had yet another woman come in, in tears, with a condition that was entirely preventable and definitely manageable, that she’d put up with for 20 years,” Miller recalls.

“She told me a very funny story about her wetting herself on the doorstep in front of her neighbour. Which is a traumatic thing to happen, but she was from Glasgow, and Glaswegian people just are funny.”

Miller asked if she could use the material in her stand-up act – she turned it into a five-minute skit, and didn’t mention that she was a physiotherapist. After the gig, four women approached her in the basement bar and said, “Me too”.

“So there was this little clique of us discussing pissing ourselves, and none of them had seen the GP,” Miller says. “But they would come and speak to a stranger in a pub. So I wrote a Fringe show about it to see if you could use humour to address the taboo, and make it funny, and evangelise that you don’t need to put up with it.”

A fun fact from her 2014 show – incontinence affects one third of women between 35 and 55. But five sessions with a physiotherapist, and 16 weeks of pelvic floor exercises can turn the tide.

In 2010, the Australian government estimated that the problem cost the national economy $40 billion a year. The figure takes into account the economic opportunities lost to women who limit their activities because they fear exposure.

“It’s quite hard to make this subject funny,” Miller admits. “There’s a lot of humour in it, but the audience is really vulnerable. So the way that humour works is that you make people feel uncomfortable with what you’re saying, and then you make them laugh, and they relax. And that’s all it is – a curve of anxiety, and then, ‘Oh, it’s alright, ha, ha, ha’.

“People who have incontinence, they live with anxiety – that’s really well-researched and understood,” she says. “The prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders among that population is enormous. Because if you’re not confident that you can get home on the bus without disgracing yourself socially, you tend not to go out very much.

“It impacts on everything that they want to do. It’s terrible for these folks.”

When public health specialist Helen Skouteris saw Miller’s routine, she realised two things – that she needed to do her pelvic floor exercises, and that she wanted to work with Miller.

“I killed myself laughing, and then I thought, ‘OK, this is a really important health issue for women’. And I didn’t know Elaine when I went to her show. She helped convince me in a safe way.

“Because you have to be motivated yourself to then say, ‘I can live in a better way. I can do something about this.’”

“I want to get a big fibreglass vulva to stick on the top of the bus, with pubes streaming in the wind.”

Professor Skouteris is Director of the Centre of Research Excellence in Health in Preconception and Pregnancy (CRE HiPP), and head of Monash University’s Health and Social Care Unit within the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine.

She’s also the Monash Warwick Alliance Professor in Health and Social Care Improvement and Implementation Science – a role that allows her to work with health professionals based in Britain, such as Miller.

The two of them have now collaborated on a paper, “A systematic review of humour-based strategies for addressing public health priorities”, which has been published online in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health.

The review analysed 13 studies over the past 10 years that used humour to communicate serious health messages related to mental health, breast and testicular cancer self-examination, safe sex, skin cancer, and binge drinking.

It found humour was an effective way of influencing behaviour – an unsurprising finding, perhaps, for advertisers working on public health campaigns. Take, for example, this Singapore government ad urging people to get their COVID-19 vaccinations:

It also found that humour is delicate – audiences can stop listening if they feel offended.

“From a practical application point of view, I know that this stuff works,” Miller says. “I know that using humour can get people to seek help, because I’ve got anecdotal evidence of it. But that’s not enough to be able to get funding out of politicians. You need to have solid, proper evidence.”

In 2019, Miller received a fellowship from Scotland’s Chartered Society of Physiotherapy to continue her campaigning. The Scottish MPs were also persuaded by Miller in her vulva suit.

“I wanted them to see that we have the answer to all of these leaky women; we’ve known the answer for 40 years,” she says. “All I need is a bit of money, and I can save you billions of pounds.”

And men can benefit, too. “If there’s no diabetes, coronary heart disease, side-effects from medication or stress, then pelvic floor exercises are more effective than Viagra,” she says.

Read more: Vaginismus: The common condition leading to painful sex

Professor Skouteris is enthusiastic about the potential of using humour in other settings, where it can defuse feelings of shame and blame that stop women from seeking help.

She has a particular interest in how best to educate women on the dangers of excessive weight gain during pregnancy – a focus of her health in preconception and pregnancy research. “It’s really easy to gain too much weight through pregnancy, it’s really difficult to lose that weight postpartum – I’ve experienced that first-hand” she says.

Miller wears the vulva suit to teach women about their anatomy – 50% of British women can’t tell the difference between their vulva and their vagina, she says.

“And that bothers me,” she says, “because all of these problems that surround women and their bodies boil down to ignorance.

“Until we have as much vandalism in school toilets showing vulvas scribbled on doors as we have willies, then we don’t have equality. We need to have equal vandalism, which means young people understanding about what their genitals are.”

Taking the message to women

During this year’s Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Miller is hoping to conduct a walking tour of the medieval city, pointing out the various spots that remind her of vulvas (“I have a strange brain – I see them everywhere”), while also offering a history of Scottish medicine and the misogyny that’s been part of the profession since it began, and continues to contribute to women’s ignorance of their own bodies.

She’s also working on a panto show called Leaking Beauty, to reach women who wouldn’t attend a comedy gig, but would go to a pantomime.

“If I can catch women’s attention in communities that are geographically remote, economically deprived, or culturally diverse, then I can survey them and find out prevalence of prolapse, and incontinence, and all of these problems that they won’t come to the clinic about,” she says.

“I want to get a big fibreglass vulva to stick on the top of the bus, with pubes streaming in the wind.”