Financial markets are a numbers fest – market indices, option prices, hedging strategies, futures markets. More and more, mathematicians are employed to help navigate a safe path through the complexity. They are the quants, or quantitative analysts.

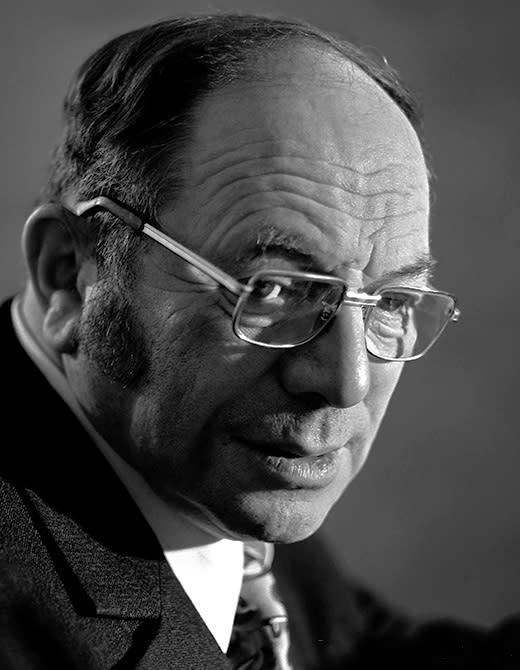

“A quant is like an engineer in the financial industry,” explains Monash University mathematics Professor Gregoire Loeper, a former quant. Between 2006 and 2015, he worked for the French investment bank BNP Paribas.

“A quant uses mathematics, mathematical modelling, computer sciences, and applies that to the financial markets,” he says. “So most of your job is to build risk management tools, methodologies and software that are used by investment banks to manage their market risk, their financial risk.”

The reputation of quants took a hit during the global financial crisis when they were blamed for triggering the meltdown by devising exotic financial products that traders didn’t understand.

Professor Loeper says this is unfair. He says the GFC was a “credit crisis”, caused by conflicted ratings agencies, a failure of lending policies and poor moral leadership. The quants and their models became “collateral damage”.

“If you don’t understand what you’re selling, you don’t sell it, you know? I’m still having these conversations, even today. Even with mathematicians. They say, financial mathematics, 'This is evil'. But mathematics is just a tool" – it’s wrong to blame a tool for what greed can do.

“If you don’t understand what you’re selling, you don’t sell it, you know? ... Mathematics is just a tool – it’s wrong to blame a tool for what greed can do."

Dr Loeper joined Monash in 2015 when the University was establishing its Master of Financial Mathematics, where mathematicians are trained to become quants.

He’s returned to mathematical research, particularly his specialty area of optimal transport, the subject of his PhD, which he uses to devise optimal hedging strategies.

“It’s a field of research that goes back to a very old problem from a French mathematician, Gaspard Monge. He was a civil engineer, and he was thinking about how to transport a pile of dirt to a collection of holes that he wanted to fill. How do you do that in a cost-optimal way?”

Monge devised a partial solution to the problem he had set.

In the 1950s, a Russian mathematician and economist, Leonid Kantorovich, returned to Monge’s problem and formulated a method called linear programming, initially as a means of optimising production in the Soviet plywood industry. In 1975, Kantorovich’s contribution to the optimal transport question earned him the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Since then, more applications have been found for optimal transport and linear programming. They’ve been used to model atmospheric flows and to reconstruct how matter was distributed in the universe after the Big Bang. In 2010 and 2018, respectively, the Fields Medal prize in mathematics – the equivalent of the Nobel – was awarded to Cedric Villani and Alessio Figalli, two renowned specialists of optimal transport.

Professor Loeper is now working on how optimal transport theory and linear programming can be used “as a way to build a risk management strategy”. It’s a relatively new field of inquiry, and he believes it has a potentially bright future, particularly in banking, where regulators are demanding that banks take ever-greater precautions to protect their assets.

In 2017, the Centre for Quantitative Finance and Investment Strategies was established at Monash in partnership with Professor Loeper’s former employer, BNP Paribas. While other banking groups have formed partnerships with universities, he says the Monash centre is “relatively unique” because “BNP also gives us access to their data infrastructure – that is very valuable”.

With the help of ClimateWorks Australia, the centre is now assessing how well-prepared the companies in the ASX 300 are for the challenges of climate change.

“The question is, how do you use all this intelligence that we have about climate change, about decarbonisation, about the economic scenarios that are considered if the world is going towards a carbon-free economy?” Professor Loeper asks.

“What are the implications of that in terms of the reallocation of capital? If people want either to hedge – to cover the risk of economic transition and climate change – or support companies that are doing the right thing to fight climate change, how do you do this when bringing a financial product in which they can invest?”

“If we bring the science that shows that carrying in your portfolio companies that are going to be negatively affected by the transition is going to affect your performance or your risk in the future, then you can make the bridge between the incentive to invest in sustainable companies and the need to manage financial risk.”

The question is a pressing one. Since the GFC, banks and other financial institutions are required to report on how exposed they are to risk – credit risk, operational risk, market risk – and that now includes climate risk.

Professor Loeper says the tools for assessing climate risk haven’t yet been established, and he’s hoping that the Monash partnership with ClimateWorks and BNP, and the French environmental, social and governance group Vigeo Eiris, will eventually be a step in the right direction. (A three-year research partnership with the School of Mathematics and Vigeo Eiris was signed in October 2018.)

Researchers are now in the process of devising a score for each of the top 300 Australian companies. “And that score is trying to predict whether that company will thrive or struggle … whether they are prepared, whether they’re doing the right thing,” Professor Loeper says. “Are they transforming their activity in the right way so that they will benefit, or will they be hurt by the changes?

“I was recently at a Responsible Investment Association in Australia meeting,” he says. “On the one hand it seems like a very good intention, only to invest in sustainable companies, etc. On the other hand, when you are a super fund or a pension fund, you have a target of financial returns that you have to meet, and these two things look somehow incompatible.

“If we bring the science that shows that carrying in your portfolio companies that are going to be negatively affected by the transition is going to affect your performance or your risk in the future, then you can make the bridge between the incentive to invest in sustainable companies and the need to manage financial risk.”

While some politicians are still denying the science of climate change, markets can no longer afford to do so. “We don’t have a choice; we have to do something, we have to do the best we can do.”

In the absence of political leadership, financial institutions and the quants who support them are assessing how to navigate the financial challenges ahead.