For 150 years Melburnians dreamed of a square, a great ceremonial space where people could relax, celebrate, protest or simply enjoy the company of their fellow citizens.

They had a word for their dream – a civic square. The word “civic” means “of the city” or “belonging to the citizens”. What they wanted was not a market, a park, an arena or a mall – Melbourne had plenty of those – but a grand piazza where people met and celebrated their identity as citizens. It would be Melbourne’s agora or forum, a place for conversation, relaxation and celebration rather than commerce.

In 2000, after decades of imagining, planning, debating and lobbying, the dream came true. Fed Square, as we now fondly call it, is not a traditional public square in the European manner, but an ingenious mix of piazza and winter garden in a quirkily post-modern idiom. People love it. Fed Square is a small miracle, a new public asset won against the tidal advance of privatisation.

The proposal to locate an Apple store, of jarringly unsympathetic design, in a prominent place on the square is a surprising and dispiriting surrender to the spirit of compromise that dogged the best efforts of Melburnians for more than a century to give their city an inspiring civic space. It dishonours their legacy. It breaches the public trust expressed in Federation Square’s own charter.

The proposed store turns the square, or at least a section of it, into a shopping precinct. It may be a first perilous step down the slippery slope towards full commercialisation.

A backward step for Melbourne

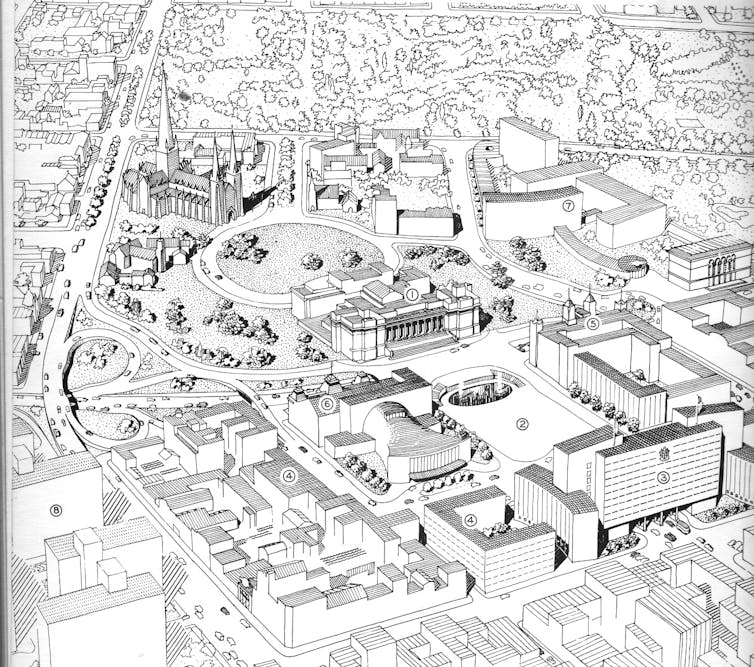

Founded by land speculators, Melbourne had always been a commercial city, a place where pragmatism often trumped idealism. Robert Hoddle, the government surveyor sent down from Sydney to draw up Melbourne’s first town plan in the late 1830s, briefly glimpsed the possibility of a town square near the site of the present-day State Library, but the idea was soon lost in the stampede of speculation.

A few enlightened souls yearned for a city built on more idealistic lines. Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe created the precious belt of parkland that enabled Melbourne to call itself a “Garden City”. Judge Redmond Barry, who championed other public institutions such as the university and public library, may have been the anonymous author of an 1850 pamphlet sketching a vision of what Melbourne “ought to be”.

“Melbourne boasts no large central square,” he lamented. The best site, between Collins, Swanston and Elizabeth Streets, opposite the Town Hall, was already in private ownership and buying it back would cost “a rather alarming sum”. But for “an object of such paramount and permanent importance”, he argued, “the money would be well spent”.

With the coming of the goldrush, the cost of reclaiming a site soared beyond reach. The dream returned only in the 1920s when city councillors debated a scheme to create a square on the site of the eastern market in Bourke Street. In 1929 a Metropolitan Planning Commission recommended “a spacious city square” next to a new City Hall at the top of Bourke Street opposite Parliament House. Such a complex “dedicated to the city’s ceremonies, art and administrative activities” would enhance “community pride”.

Artists and writers, influenced by European experience, also called for a square as an antidote to Melbourne’s notorious puritanism. In 1935, the artist Norman Lindsay declared:

Public squares, with their surrounding cafés and orchestras, the pleasures of the promenade free to the poorest, refreshment cheap and good at any hour – when these are denied there is little for people to do but make a dash for the pub, frequent the cinema or go back to their hutches like good little rabbits.

A new postwar mood of civic idealism reignited interest in a civic square. Plans for squares at the top of Bourke Street, in Swanston Street and over the Flinders Street railway yards were unveiled, energetically debated – and shelved. Journalist Keith Dunstan, a fond but sceptical observer of the Melbourne scene, mocked “Melbourne’s square dance”.

Commerce delivered failure

By the 1960s, as shoppers migrated to suburban malls, retailers joined the cause. They argued that a city square would enliven the city centre and keep the threat of a “doughnut city” – a dead centre surrounded by lively suburbs – at bay.

The idea that the square might pay for itself through the “external” benefits to city traders introduced a new set of expectations into the public debate. People began to speak of a “city square” rather than a “civic square”. The idea of a square that would pay for itself was appealing to civic leaders and city businessmen alike.

When Melbourne at last got a kind of square in the early 1980s it was in the bastardised form of a “civic” space that doubled as the forecourt of an international hotel. The council bought a narrow strip of land along Swanston Street between St Paul’s Cathedral and the Town Hall, and split it in half, selling one portion to the hotel and retaining the other as an ineptly named “square”. It was neither fish nor fowl and it never really worked. It was crippled by compromise.

The people who designed and managed Federation Square seemed to have heeded the lessons of that failure. The space is as generous and inspiring as the old square was cramped and miserable. At the time I took a keen interest in the arrangements to ensure public access by community groups and political protesters. They appear to have been administered in an impressively generous non-partisan way.

From the beginning there was an expectation that, along with public bodies like the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) and SBS that would occupy the main spaces, provision would be made for restaurants, pubs and other commercial activities that complemented its civic character. But the square’s Civic and Cultural Charter was carefully written to ensure civic values would predominate.

When I read it, I was reassured by the repeated use of words like “public”, “civic” and “meeting place”. I took comfort from the requirement that any commercial activity would have to link to the purposes of its main (cultural) users and be subordinate to the “civic and cultural” character of the square as a whole.

Would we demand Trafalgar Square turn a profit?

The proposal for an Apple store appears to be inspired, in part, by the expectation that Federation Square should pay for itself, and that since it is running a deficit, it must find a lucrative new tenant. Fifty years ago Melbourne’s city fathers (as they all were then) believed a square would pay for itself through the benefits it brought to the city as a whole.

That argument is still advanced, but selectively, to justify government financial support of the Grand Prix and the Australian Open, which run for a weekend and a fortnight respectively. Federation Square runs 365 days a year and draws locals and visitors from much wider constituencies than motor racing and tennis enthusiasts. The external benefits it brings to the city are literally immeasurable.

It would not occur to the average Briton to ask whether Trafalgar Square is paying for itself, much less to install an Apple store beside Nelson’s Column. Isn’t it time we grew up and recognised that not everything that is important to our collective life has a price? That commercial values do not trump civic ideals?

By signing over part of a sacred civic space to a multinational company we may undermine the very ideals for which it was created. Opinions of the proposed architecture of the Apple store may well differ. But the most important issues posed by the proposal are not architectural, or economic.

Federation Square is already an important part of Melbourne’s history, not just as a monument to the centenary of the nation, or for the symbols of civic and national identity it incorporates, but as the legacy of a long tradition. Going back to the ancient Greeks, and reinforced by generations of Melburnians who fought for a square, it’s a tradition that puts civic values and virtues, our responsibility to our fellow citizens, at the heart of our collective life.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. Graeme Davison does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.