The world economic crisis triggered by COVID-19 gives Australia a historic opportunity to debunk and dispel the Productivity Commission’s orthodoxies on economic globalisation.

For the past 40 years, the Australian economy has been globalised according to received neoliberal wisdom based on:

- Growth – that is, reducing production and labour costs to chase higher rates of capital investment and profit.

- Competition – that is, removing trade barriers to open our markets to low-margin imports and high-margin exports.

- Deregulation – letting multinational instruments and special interests dictate our industrial policy with little government planning in the way.

Fast-forward to 2020, and the coronavirus pandemic black swan event is forcing the coalition government to reverse decades of bipartisan support to the invisible hand of globalisation that has tightly gripped legacy Australian manufacturing and its good-quality jobs.

In the very first days of pandemic-related havoc, I explained the worst-case scenario for Australia’s economic system. Sadly, my negative outlook appears closer to becoming reality than initially expected. In short, I argued that the disruption to global supply chains caused by the spread of COVID-19 is poised to severely hurt Australia’s workers and small-medium enterprises in three successive stages, centred on:

- increased supply price

- reduced value of money

- income deflation.

Essentially, the latest economic developments are confirming my initial point that the emerging crisis of globalisation is fast moving from the periphery to core areas of the world economy. This is poised to make the next generation of Australians the first in our country’s history to be significantly poorer than their parents and grandparents.

Courtesy of COVID-19, we can toss in the bin most of the established literature on macroeconomic policy surrounding global value chains.

At any rate, once the health emergency is under control, we should expect polarising policy debates on how to salvage Australia’s economy and avoid generational impoverishment. As always, ruthless politics will decide winners and losers, or simply who is going to pay for whose rescue.

Judging from early signs, we can already identify one emerging narrative cutting across the fading right-left political cleavage: the V-shaped recovery.

This discourse faithfully relies on the International Monetary Fund’s projections that Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP) will shrink by 6.8 per cent this year, but will almost symmetrically rebound by 6.1 per cent next year.

The subtext of the V-shaped recovery is that by the next federal vote in 2022, with the hopeful help of the coronavirus vaccine, Australia can snap back to where and what it was at the end of 2019. We would still end up with a significant public debt, but the story goes that it won’t be so painful to repay thanks to historically low interest rates, which the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) says it will keep this low for quite a while longer.

The unfettered globalisation days we knew up to very recently are all but gone.

And … we lived happily forever in the globalised economy as if COVID-19 never happened? Not quite so for all those, including myself, who take the IMF and RBA’s projections for what they are – mere estimates based on economic and geopolitical assumptions that are being overridden by the pandemic black swan.

Indeed, courtesy of COVID-19, we can toss in the bin most of the established literature on macroeconomic policy surrounding global value chains.

Strengthening local economies

I've asked independent economist and former Monash Business School academic Dr David Treisman, of CF Gauss & Associates, to validate my argument.

Dr Treisman pored over relevant literature to find empirical tools that still hold up for assessing the quandaries facing the Australian economy in this changed world – that is, if you accept that the world will not snap back into perfect shape post-pandemic.

The most solid and still valid argument we could find is based on a recent article by a Bank of Canada staff member, Yukio Imura, who reassessed trade barriers with global value chains.

Imura's paper is rather convoluted, but his message is that any of the three trade restrictions contemplated under analysis has adverse implications for macroeconomic performance. However, he finds that, on a firm level, the same trade restrictions have a positive effect for multinational companies (MNC) based in the country applying the trade restrictions.

Essentially, this confirms the counterintuitive notion that breaking the chains of unfettered globalisation strengthens local economies, even if the global sum of profits/growth retreats. In other words, targeted protections redistribute the benefits of international trade more fairly between the global core and the domestic peripheral economies.

Read more: Exposing the faultlines of unfettered globalisation

Would this hold true in Australia’s post-pandemic road to recovery? To this avail, Dr Treisman extended Imura's findings into a simulation in the Australian context.

Imura considered the following three trade restrictions and real examples occurred in the heat of an economic crisis, and targeted specific economic behavioural outcomes:

- Tariffs on final-good imports, affecting mainly the purchasing choice of households in the policy-imposing country (for example, in 2009, Russia increased import tariffs on used foreign cars and trucks).

- Tariffs on intermediate-input imports, directly affecting the cost of production for producers in the policy-imposing country (for example, the recent imposition of import tariffs on aluminium and steel by the US administration).

- Barriers to accessing foreign markets, affecting international trade mainly through the extensive margin of exports, limiting the presence of foreign exporters in the destination economy (for example, in 2009, Argentina introduced non-automatic licensing requirements on its imports of auto parts, textiles, TVs, toys, shoes, and leather goods).

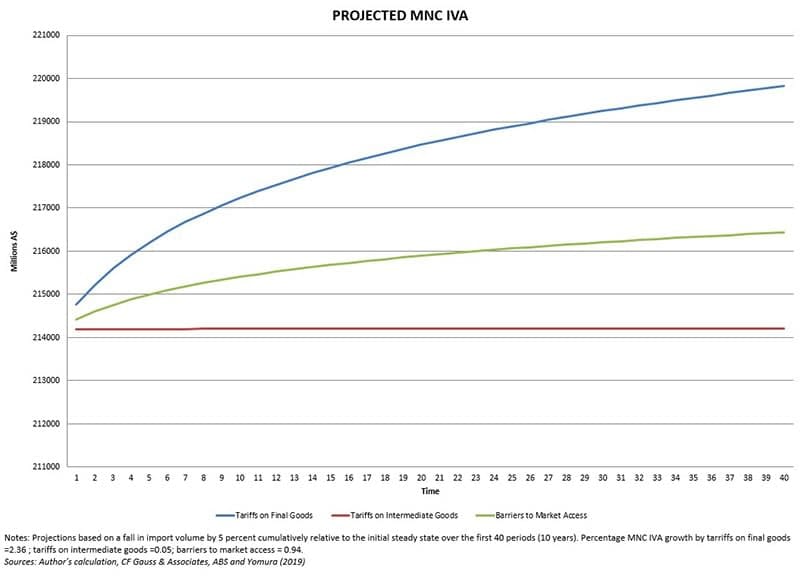

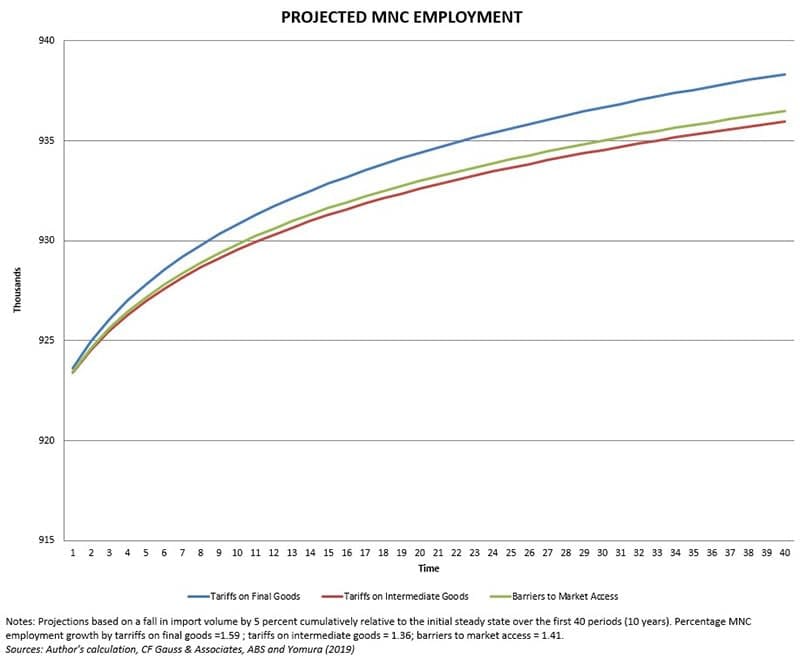

As Dr Treisman’s charts below show, employment and production output (industry value add – IVA) are the two areas that multinational corporations (MNC) gain most from the country imposing the trade restrictions.

The charts above and below paint the picture for Australia’s post-pandemic economy, following Imura's parameter of a fall in import volume by 5 per cent cumulatively, relative to the initial steady state over the first 40 periods (10 years).

Indeed, the figures show that targeted trade restrictions in Australia would trigger increases of production on final goods between 0.05 and 2.34 per cent, as well as employment increases between 1.36 and 1.59 per cent.

Considering that by most recent ABS figures, MNCs in Australia support more than one million jobs and contribute about $220 billion – about a fifth – of national production, the lesson is clear: At this critical stage, carefully targeted deglobalisation would significantly boost Australia’s industries and jobs in key sectors of the economy, particularly manufacturing, mining and wholesale trade.

In conclusion, this is the time for bold and unorthodox measures, and not for wishful thinking of V-shaped recovery. The unfettered globalisation days we knew up to very recently are all but gone.

Of course, targeted deglobalisation alone is not sufficient to shield Australians from generational impoverishment. A more planned and cooperative industrial policy is also needed to benefit the real interest of Australian workers and producers ahead of abstract figures of global growth.

By way of example and suggestion, it's crucial that the Australian economic sectors listed above join forces with public bodies to develop innovative industrial processes.

This is proven to work best within regional clusters of integrated networks of infrastructure, such as the Monash precinct, which brings together in Victoria world-leading researchers and multinational industry partners, contributing A$9.4 billion to the Victorian economy each year, supporting more than 14,000 businesses and supports more than 95,000 people.