Using data from 2016 to 2019, a Monash University research team has developed what they now know to be the world’s first index of environmental health risks, mapping Australian geographical locations against local environmental risks and associated causes of death.

The study, by the University’s Climate, Air Quality Research Unit (CARE) at the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, is now complete, and the numbers are in.

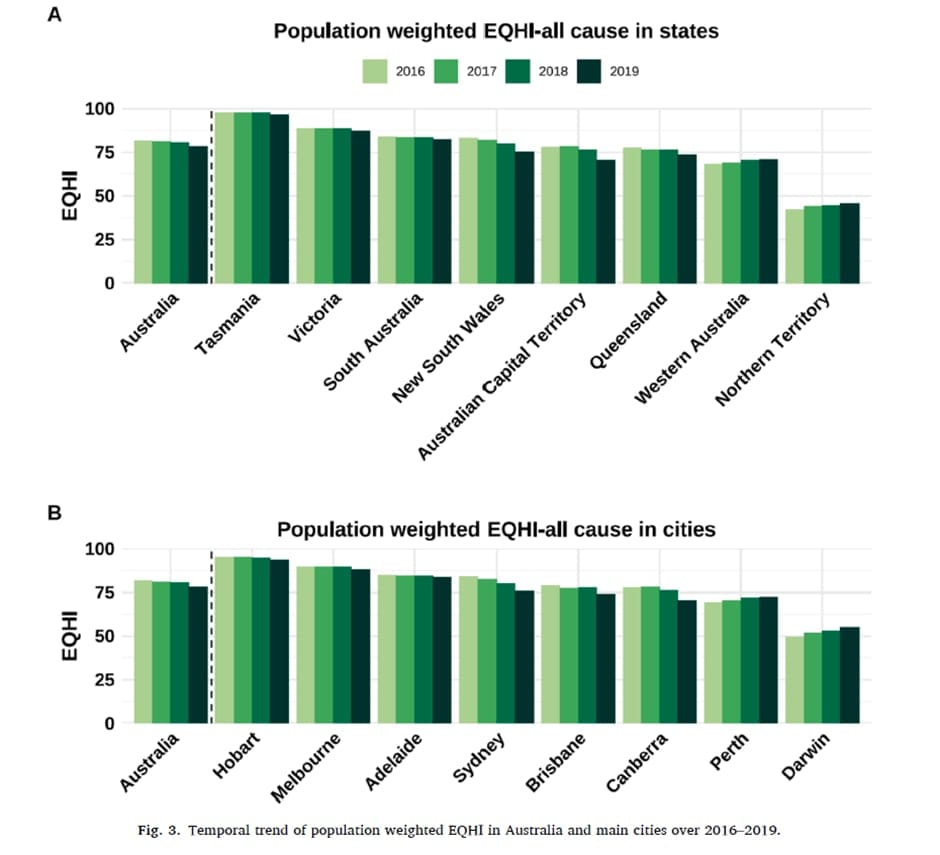

Tasmania came in as the healthiest state to live in, with Hobart the number-one capital city. The Northern Territory and Darwin were rated the unhealthiest.

Australia’s south, east and southwest coastal regions generally scored higher than inland and northwest regions on a scale of zero to 100, with higher numbers indicating better environmental and health conditions.

But the real and sustained interest here is not necessarily where – at a particular time – it may be better to live, but the thorough model the research team built to find answers.

The team’s paper is now published in Environment International.

“We established, to our knowledge, the first tool to quantify and communicate environmental health risks using three types of mortality data and 12 environmental factors,” it reads.

“This … provides a robust framework to assess environmental health risks and guide targeted interventions. Our methodology can be adapted globally to standardise risk evaluation.”

The 12 environmental and socio-economic factors are:

- Fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

- Ozone (O3)

- Green space: Normalised Difference Vegetation Index

- Night time light

- Mean temperature in summer

- Mean temperature in winter

- Temperature variability in summer

- Temperature variability in winter

- Relative humidity

- Building density

- Road density

- Socio-economic status: The Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage

Targeted efforts needed

Senior author and Monash University Distinguished Professor of Global Environmental Health and Biostatistics in the SPHPM, Yuming Guo, says the study is a tool to measure the environmental conditions, and highlights the need for targeted efforts to improve environmental conditions in regions with lower scores, to reduce health risks, and promote wellbeing.

These “scores” – formulated by the team – are called the Environmental Quality Health Index (EQHI).

The researchers analysed 2180 areas classified by the Australian Bureau of Statistics as Statistical Areas Level 2 with an average population of 10,000 people, including suburbs, towns and cities.

The 12 environmental factors are then run through data regarding cause of death and other mortality data, which is how Hobart and Tasmania came out on top, because it had lower environmental risks and better conditions that reduced death risk.

Professor Guo says from 2016 to 2019, the proportion of areas with the highest EQHIs went down by 6%, but more than 70% of Australians still lived in high-scoring areas.

“When accounting for population distribution, this study found that scores improved in Perth and Darwin, decreased in Sydney, Canberra and Brisbane, and remained stable in Melbourne and Adelaide,” he says.

Read more: The invisible killer lurking in our cities’ air

The difference between Hobart and Darwin was “significant,” he adds. Hobart showed “exceptionally good results” (highest scores), while Darwin had the lowest scores, reflecting poorer environmental and socio-economic conditions.

He says Melbourne’s higher score than Sydney “reflects a combination of better air quality, favourable climate and other environmental conditions, and higher socio-economic advantages, which are linked to lower health risks.”

Air pollution, climate change factors

The paper states that 24% of global deaths are related to environmental risk factors such as air pollution and climate change.

The paper says research into this – such as on air quality, road density, night light, green spaces and socio-economics – has so far been “narrowly defined, limiting the ability to capture the cumulative and multidimensional impacts of diverse environmental factors”.

It points to gaps where different exposures to different risks are not integrated together.

“These gaps highlight the need for a comprehensive approach that evaluates the combined health effects of multiple, distinct environmental exposures,” it reads.

The researchers believe existing environmental quality indices often failed to account for the varying health impacts of different exposures, and excluded socio-economic status indicators.

Professor Guo says the EQHI could be integrated into government policy and public health by “disseminating the results to policymakers to inform environmental improvement and health interventions [through] educating the public and stakeholders on how to interpret and use the EQHI, and collaborating with local governments and local organisations to implement targeted measures in low-scoring areas”.