For millions of refugees worldwide, education represents far more than the acquisition of knowledge. It’s a cornerstone of dignity, resilience, and empowerment that enables individuals to rebuild their lives and contribute meaningfully to society.

As of 2024, more than 120 million people have been forcibly displaced globally, with 31.6 million classified as refugees (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2024).

Among these refugees, approximately 14.8 million are of school age, yet nearly half are not enrolled in any form of education, a staggering figure that reflects a global failure to deliver on commitments outlined in the 1951 Refugee Convention and the Sustainable Development Goals.

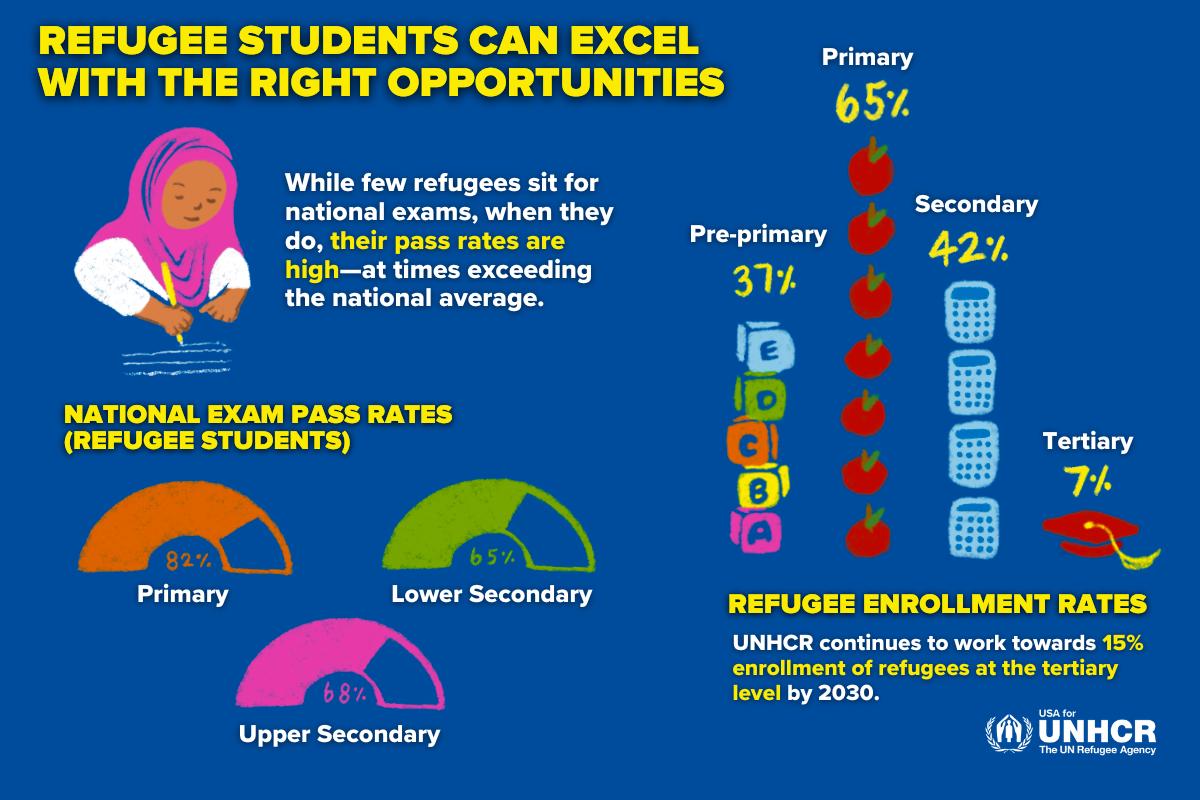

Among those who are enrolled, stark drop-offs occur at every educational level. Only 65% attend primary school, 42% make it to secondary education, and just 7% progress to tertiary education compared to a global average of more than 40%.

These numbers paint a sobering picture of missed opportunities and systemic barriers that continue to hinder the potential of displaced populations.

It also illustrates how much more work is needed to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, which is:

“... to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

The barriers refugees face in accessing education are varied and deeply structural. Many host countries lack inclusive policies that allow refugee children to enrol in public schools or take national exams.

Where legal access exists, financial constraints often present a major hurdle. Yet despite these daunting challenges, the evidence overwhelmingly shows that when given access to quality education, refugees thrive.

UNHCR reports that in countries where refugee students take national primary school exams, 82% pass, which is a rate comparable to, or better than, that of local students.

Education fosters not only academic achievement, but also personal growth, psychological wellbeing, and a renewed sense of purpose. It helps young refugees regain a sense of normalcy, builds their confidence, and provides hope for the future.

Importantly, education benefits not just refugees, but their host communities and the global society at large.

Studies by the Brookings Institution and UNESCO highlight the role of education in promoting peace, reducing poverty, improving public health, and facilitating economic integration.

Educated refugees are more likely to contribute to their new communities, participate in civic life, and engage in productive employment. When supported, they become leaders, educators, entrepreneurs, and change-makers.

Recognising this, organisations and institutions across the world are developing new strategies to improve refugee education.

UNHCR and its partners are committed to achieving enrolment of 15% of young refugee women and men in higher education by the year 2030 – the 15by30 target.

Based on 2022 population data, achieving 15% enrolment in 2030 will mean that approximately 600,000 young refugee women and men will be participating in an enriching academic life.

In Malaysia, the CERTE (Connecting and Equipping Refugees to Tertiary Education) taskforce, led by Monash University Malaysia’s School of Business, is identifying and supporting refugees who demonstrate the motivation and academic potential to pursue higher education. This initiative is particularly vital in Southeast Asia, where legal and policy barriers often limit refugees’ access to formal schooling.

Despite promising developments, funding remains a critical bottleneck. Education receives less than 3% of total global humanitarian aid, most of which is directed toward emergency and primary education.

Secondary and tertiary education are critically underfunded, limiting opportunities for older youth and adults to advance their skills or pursue careers.

A long-term commitment from donors, governments, and the private sector is essential to fill these gaps.

Equally vital is systemic reform

Host countries must adopt inclusive policies that remove legal and administrative barriers to education for refugees.

Curriculum should be adapted to reflect students’ lived experiences and home languages.

Recognition of prior learning and flexible accreditation pathways are necessary to accommodate non-linear educational journeys.

Teacher training, trauma-informed pedagogy, and gender-responsive programming are key to ensuring classrooms are safe and welcoming for all.

Gender equity must be a priority

Refugee girls are half as likely as boys to enrol in secondary education. Risks such as early marriage, gender-based violence, and domestic responsibilities disproportionately affect girls’ ability to attend and complete school.

Targeted scholarships, female mentorship, and protective policies are needed to close this gap and unlock the full potential of half the refugee population.

To build sustainable, inclusive education systems, refugee voices must be central to program design and implementation.

Refugees are not passive recipients, but they are agents of change. Empowering them through education equips them not only to survive but to lead and innovate, contributing meaningfully to both their communities of origin and those that host them.