The emergence of new RNA virus variants isn’t unusual, and coronaviruses are no different. With increased virus replication, we give the virus a higher chance for mutations to occur, hence the new variants.

A majority of these new mutations are innocuous. However, some of them may evolve to become more infectious, or evade human antibody responses, a phenomenon called “convergent evolution”, observed in many past pandemics.

We’ve witnessed SARS-CoV-2 (the causative virus for COVID-19 disease) mutating rapidly and acquiring a constellation of mutations. The Alpha variant, for instance, is 50% more transmissible than the original Wuhan strain.

Now, following the Beta and Gamma variants, we have the Delta variant, which shows 60% more transmissibility than the Alpha variant. The Delta variant is primarily responsible for the “second wave” in 98 countries.

Delta Plus, Lambda, and the third COVID wave

Now, the “third wave” is expected to emerge from the Delta Plus variant (B.1.617.2.1/AY.1) that has appeared across 12 countries, including India, UK, Poland, Switzerland, Portugal, Russia, Japan, Nepal, China, Canada, Turkey, and the US.

The Delta Plus variant is resistant to antibody cocktails (artificially produced monoclonal antibodies), binds more tightly to the ACE2 receptor, thereby increasing transmissibility, exhibits resistance to COVID-19 drugs, and evades the immune response elicited by vaccinated individuals.

The mutation (K417N) acquired by the Delta Plus variant is not something new. It was also present in the Beta variant.

The Lambda variant (C.37 or B 1.1.1) was detected as early as December 2020 in Lima, Peru. This variant has been reported in 90% of all cases in that country. Currently, more than 29 countries have detected this variant.

It’s noteworthy how this variant, although detected early, showed slow rates of infection initially, but has now become the predominant variant in Peru, clearly showing its edge in transmissibility and infection over other variants.

It’s interesting to note that this variant has seven single-point mutations and one deletion mutation (few amino acids missing from the protein sequence), all in the spike protein. The spike protein is the surface protein on this virus, and is very antigenic, meaning that it’s the primary target for immune recognition by our system.

The sequence that’s deleted in this Lambda variant corresponds to the region of the spike protein responsible for this immune recognition by our system.

Hence, the Lambda variant with its new deletion may make it more capable of immune escape in vaccinated individuals. Also, two (L452Q and L452R) of the seven-point mutations in the spike protein of the Lambda variant may result in increased antibody escape, thus rendering antibody cocktails ineffective.

All these factors directly contribute to increased infectivity by the Lambda variant, and a drop in the overall efficacy of the current vaccines.

Therefore, the emergence of new variants is a natural phenomenon, and the presence of Delta, Delta Plus and Lambda variants in Malaysia will not, and should not be surprising. The new variants don’t have to be transported from another country by a carrier or infected person. It emerges from the extensive cycles of replication within the infected cohort.

Lambda coronavirus variant - CSIRO: The Lambda variant has an eclectic set of mutations, many of which appear to be immune evasions — that is, allowing the virus to evade a person’s immune response. https://t.co/FTL1bXmxfJ— @tetralympus (@dragonsaerie) 15 July, 2021

The state of play in Malaysia

Looking at the current numbers in Malaysia, it’s clear the virus is actively proliferating and infecting and defeating all our predictions on levelling the curve following our severe lockdown measures.

These new variants may very well be in our Malaysian population, and due to their increased transmissibility, they might be spreading quickly within our communities undetected – thereby driving our case numbers up.

We must understand that the detection of new variants is directly related to sequence-based surveillance, laboratory studies, and epidemiological investigations.

At the start of the lockdowns, we detected more than 6000 daily cases, with the number of positive cases directly proportional to testing.

In contrast, the detection of variants is directly proportional to the sequencing of infected samples. Looking at the steady increase in infected cases despite the lockdowns, it seems clear that the infection dynamics of the virus have changed, and its transmission and infectivity have improved. These are signature traits of the new variants described above.

Whole sequence-based surveillance of viruses and detecting point mutations require the expertise of personnel and infrastructure that many developing countries lack. This delays the early detection of new variants, resulting in them going undetected until they overtake their predecessors due to their efficient transmission rates.

Once they become the predominant strain, they become easier to detect. So, given our rate of detection of mutations following virus sequencing, it may take a while before we actually run into detecting the Delta Plus or Lambda variant.

The virus has immersed itself well in the human population, hence making it impossible to eradicate.

The World Health Organisation is correct in stating that “it will never go away”. This said, we have to devise ways to coexist with this new infectious agent, just like we coexist with many other known infectious agents.

By far, polio is the only virus that has been “almost” eradicated by humans, and this has been eased by the fact that this virus doesn’t mutate as frequently.

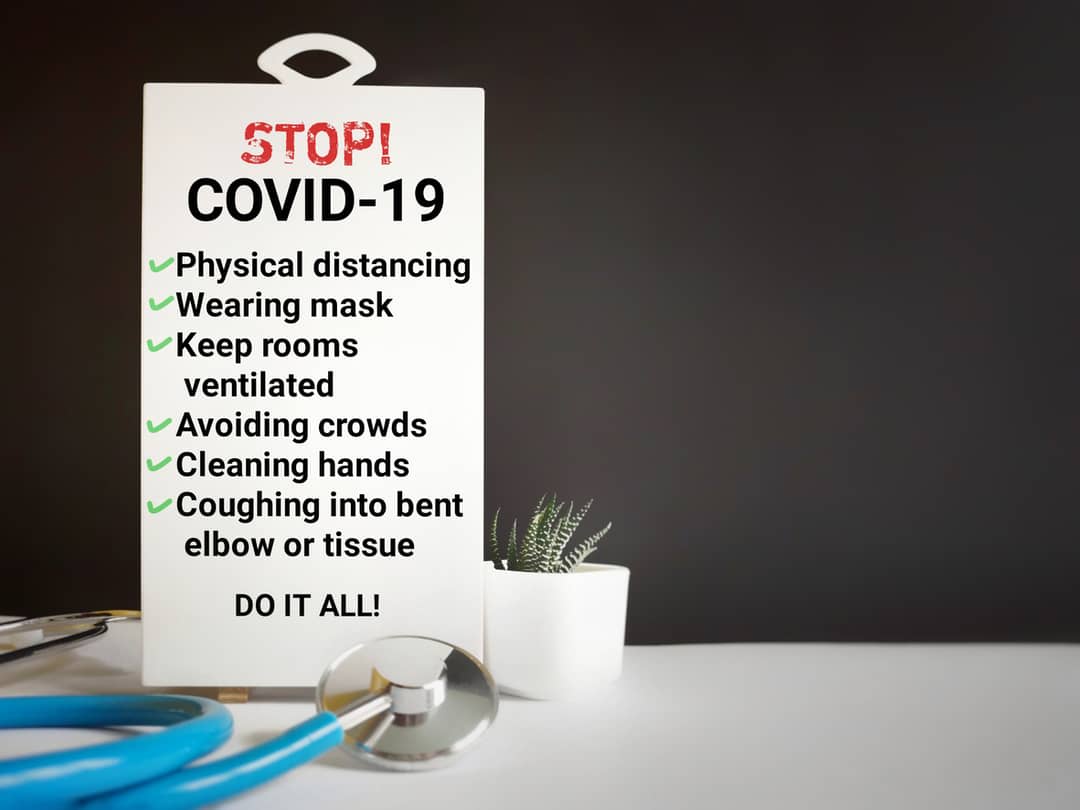

In principle, lockdowns are effective at stopping the indiscriminate spread of the virus, but experience has also shown us that this time should be used by the healthcare institutions to primarily focus on capacity-building and medical supply chains.

Once the lockdowns are relaxed, there are bound to upsurges in cases that will have to be handled efficiently.

Undoubtedly, face masks and social distancing help curb the spread of aerosol, and must be implemented in crowded places, metro trains, public places, grocery stores, and indoor gatherings.

Recently, research from the Francis Crick Institute has categorically underscored the need for a second jab of the same vaccine due to the increasing number of emerging variants.

This study, published in The Lancet, has emphasised the need for newer jabs directed against the new and predominant variants.

All these actions will still let new variants emerge, but the new waves will be less lethal than the past if we learn from each wave and incorporate newly-acquired information.

If we can’t defeat the enemy, let's learn to live with it.