When nine public housing towers in Flemington and North Melbourne were locked down to stop the spread of Coronavirus, Abby Wild worried about the 3000 people trapped inside. What did they understand about what was happening to them, and why?

Wild trained as a neuroscientist before undertaking a PhD in criminology, examining how to engage prison populations in rehabilitative programming. She also works as a researcher at BehaviourWorks Australia, a research enterprise that’s part of the Monash Sustainable Development Institute, which develops strategies for how to help bring about behavioural change as a way of tackling social, environmental and organisational problems.

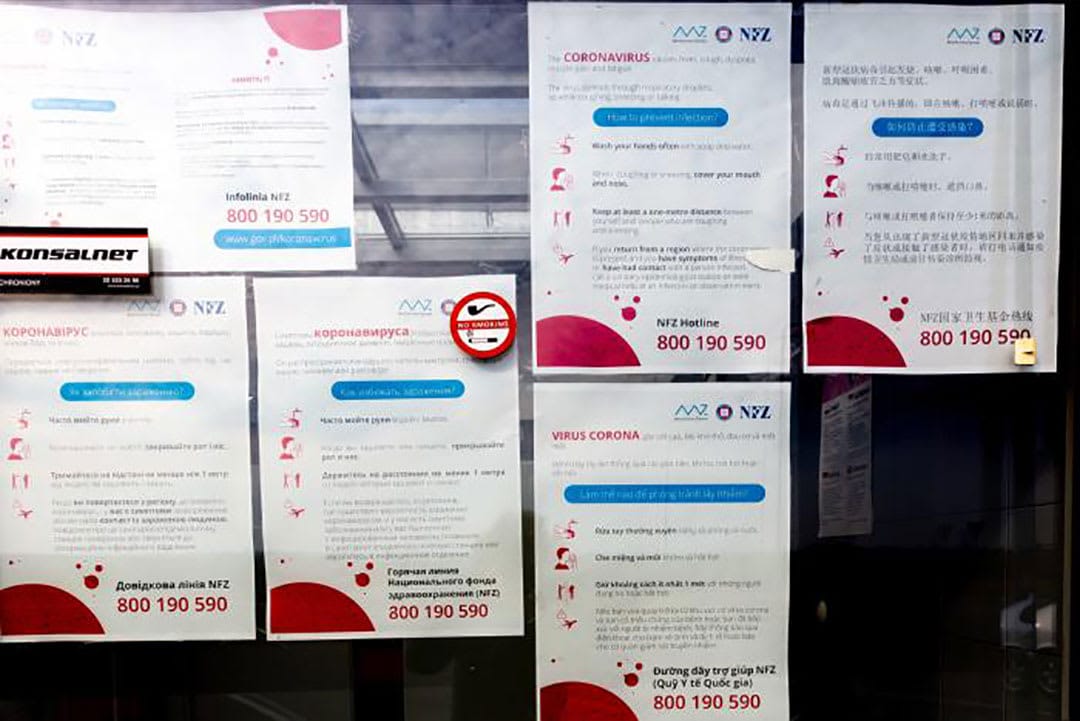

In Melbourne, the challenge of persuading residents to follow social distancing, mask-wearing and hand-washing protocols has been complicated by the city’s outstanding diversity. Melbourne is home to 260 language groups, many belonging to newly-arrived migrants. It’s Australia’s – and possibly the world’s – most multicultural place.

“The way that COVID has impacted multicultural communities is a sensitive topic,” Wild says. It’s so sensitive that some officials are reluctant to mention it at all, because of concerns that “it can lead to scapegoating or stigmatisation of certain groups”.

In NSW, for instance, the challenges of communicating COVID-related health advice to diverse ethnic and linguistic groups appears to be rarely mentioned by government officials. In Victoria, this has been discussed much more openly, says Wild.

Culturally and linguistically diverse communities are also vulnerable to misleading or dangerous rumours about the virus.

Wild was lead author in a study in which researchers from BehaviourWorks – including Dr Brea Kunstler and Dr Denise Goodwin, and Professor Helen Skouteris from the Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation – collaborated with 12 leaders from Victoria’s multicultural communities to examine how best to communicate COVID-related health information.

The study recommended establishing a national body to advise authorities on public health messaging in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities. Wild suggests that approaches to support effective communication with multicultural communities should be incorporated in government strategies from the beginning. The advice recognises that effective communication is more complicated than simply translating English messages into other languages.

Read more: Nine Melbourne tower blocks put into 'hard lockdown' – what does it mean, and will it work?

Some new arrivals, including refugees, may need information about how viruses are transmitted, for instance, because they may not have learned this at school. Some may be mistrustful of authorities, because they could not trust their government at home. Others might be in low-paid, insecure work, cannot work from home, and have more than one job, which makes them reluctant to be tested, or to take time off. Or they may live in crowded conditions, making social distancing difficult – something that simple education cannot overcome.

These “structural factors” contribute to the “disproportionate vulnerability of CALD communities in Melbourne,” Wild says.

Communicating information needs a comprehensive approach

Translating government information into all languages and dialects is complicated and requires a comprehensive approach.

“Groups told us that they were completely missed,” Wild says, “and it wasn't necessarily because the government didn't have that group on its radar. One of our co-authors is a South Sudanese community leader, and he mentioned that there were several South Sudanese languages spoken in the Melbourne community. But Arabic translations of government health information were disseminated to the South Sudanese community, even though few members of, at least his community, read and write Arabic. And even those who do were not necessarily familiar with the ‘high Arabic’ that was used in the government translation.”

When the pandemic began, the World Health Organisation warned about the “infodemic” of false information about COVID. CALD communities are also vulnerable to misleading or dangerous rumours about the virus, Wild says. The best antidote is the intervention of “trusted messengers” who provide reliable information to community members on the forums and platforms that they visit.

The identity of these messengers will vary in each community. For some it will be religious leaders, for others it might be bilingual nurses, doctors or teachers. Friends and family members could be the most trusted messengers of all, Ms Wild says, because they’re motivated by genuine concern, and can tackle an individual’s misconceptions without judgment – just as in many other communities.

Utilising different platforms to convey the message

The most effective channels to deliver COVID-specific information can vary from group to group, she says, and may also vary within the group depending on their age. Older people might listen to the radio; younger people might use social media platforms such as Facebook; mainland Chinese migrants like WeChat; and so on.

Research shows that trained interpreters in health settings are highly effective communicators, because they relay information accurately and establish rapport with patients – but Wild concedes that they’re not available in every language, and there are shortages even within settings such as hospitals.

Read more: Multicultural leaders explain how best to communicate COVID-19 advice to diverse communities

“One of our co-authors who works with the Islamic Council of Victoria mentioned how significant it was that Brett Sutton and members of his team have committed to hosting a series of interactive forums where people can ask questions back and forth to health authorities,” she says. The information itself is important, but so is the “messaging”, when an official figure makes a gesture of this kind.

“You can ask your specific question, and you feel the health authorities are really trying to protect your community. The expressive function of that is really important.”

The report also suggested that community leaders be deputised to help fashion communication strategies for their particular group, giving them authority and support to craft messages for their communities – which was more efficient than expecting the health department to have all the answers.

Dedication to communities stands out

Wild says an unexpected bonus of the research, for her, was meeting people with “extraordinary levels of dedication to their communities”.

“It felt very different to me than the media stories that were hand-wringing about the problem that these communities presented,” she says. “It felt like a lot of people were already coming up with lots of inventive ways to try and combat misinformation, reach people who hadn't heard things, call people every hour to see if they had more questions before they went in to get tested. Figuring out a way to amplify their efforts was a challenge worth trying to take on.”

Just as she was not the only researcher concerned about public housing residents when the project began, she was also not the only one affected by the resourcefulness and kindness that CALD community members displayed towards one another.

“Sometimes academic papers don’t capture the process very well, but that was one of the most satisfying parts for us,” she says.