One of the most visually arresting aspects of COVID-19 lockdown was the empty streets as people sheltered in their homes, going out only when absolutely necessary.

Those days seem a distant memory as the economy reopens, and people flood back to schools, shops, restaurants, and offices.

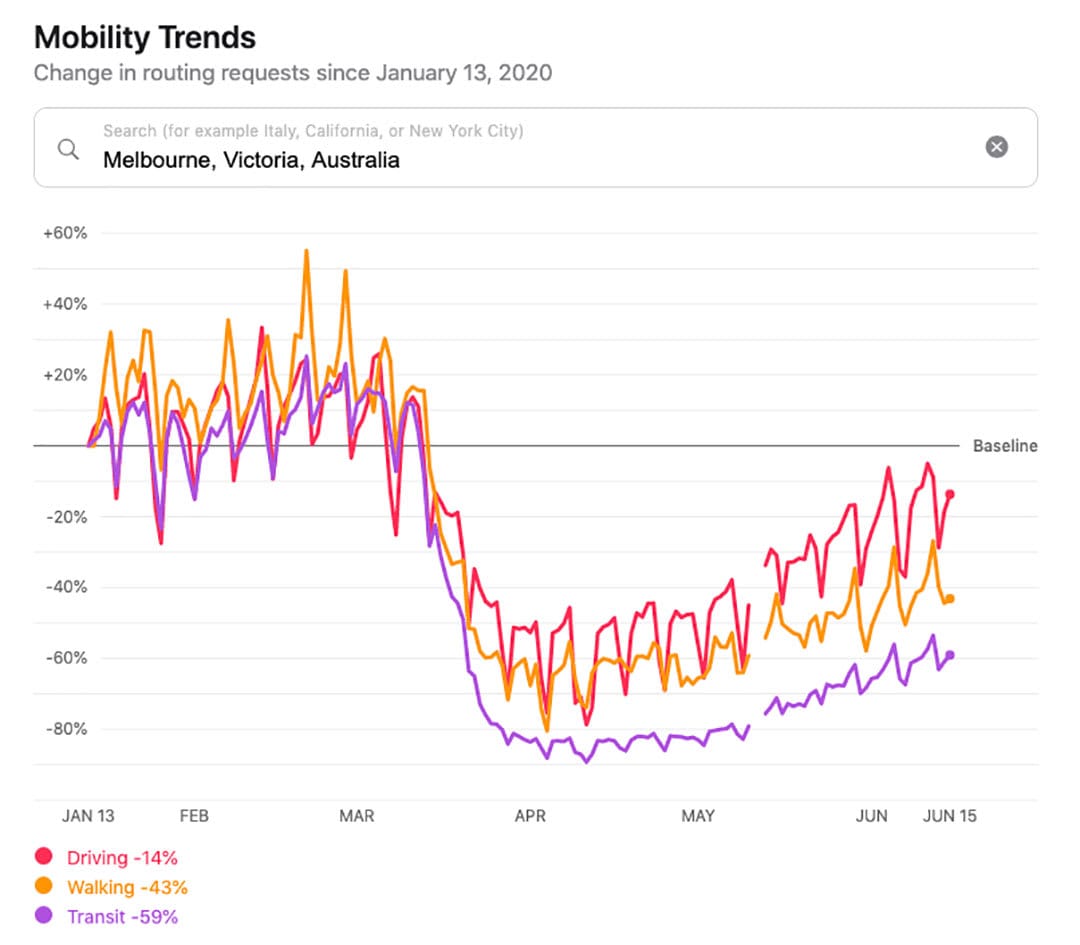

Apple Maps data (granted, an imperfect measure of traffic levels) shows that after a huge drop, driving levels are nearly back to where they were before COVID-19 restrictions – and this is at a time when employees are still required or urged to work from home if they can.

Meanwhile, public transport ridership still lags far behind driving as commuters fear being in close contact with others. A surge in driving and a drop in public transport usage points to one thing – we’re headed towards city-crippling carmageddon.

If people are unwilling to return to public transport, we simply can’t fit all the extra cars on the road.

Take Melbourne’s city centre as an example, where on a normal day 220,000 take public transport to work, compared with 117,000 in a car, and 37,000 who walk or cycle. If people practise complete social distancing, only 10 to 15 per cent of those 220,000 can fit on public transport, leaving 198,000 to find another way to work.

There’s no spare capacity on our roads, and nowhere to park those cars if they manage to fight their way through the gridlock. Staggered start times and teleworking can only do so much to reduce that demand.

A return to public transport must play a key role in the future of our cities. Japan and France saw no COVID-19 clusters on their transit networks, suggesting that public transport can be safe even during a pandemic.

But in the meantime, what else can we do to manage the massive surge in demand that’s about to hit our roads?

A price on supply and demand

One potential solution involves congestion charging – requiring people to pay more to use roads where the demand is highest.

It’s a common misconception that the average motorist is “already” paying for the roads at the petrol pump. Yet the current funding system sees less than half of the cost of our road covered by fuel excise, and that income is steadily decreasing as cars become more fuel-efficient.

Meanwhile, governments are investing billions in big-build road projects; the benefits go to the future users of that road, but the costs are paid for by all taxpayers whether you drive or not.

Read more: Returning confidence in public transport in a post-COVID-19 world

The benefits of congestion charging have been argued time and again by many. Infrastructure Australia, Infrastructure Victoria, the Grattan Institute, and even motoring clubs such as the RACV and RACQ all agree that the current system of funding roads should be replaced by a system where people who drive in the busiest locations and times should pay more than people who drive at times and places where the roads are not busy.

The average motorist dislikes the idea of congestion charging because it feels like paying extra for something they “already” pay for. Yet in cities that implement the charges, motorists quickly change their minds – when they see it in action, they realise how much easier it makes their own commute.

Congestion charging works. It works in London, Milan, Stockholm, and Singapore. It can work in Australia, too.

London.

There are many options in implementing congestion charging – distance-based charges, a cordon around the busiest part of a city, even tolls that vary depending on how busy the road is that day.

That doesn’t mean that any version of congestion charging will succeed; some attempts fail in practice because of a lack of understanding of the relationship between charges and their effect on traffic.

Recently, researchers have been exploring novel scientific tools to make this link, and demonstrating that city-wide congestion charging schemes can be effective and fair.

A recent study suggests that in the long term, people will return to public transport, just as they did after SARS and 9/11.

Being fair is a key concern with any change to road pricing. The impact on low-income drivers is often cited as a reason to hold off on congestion charging, but there are many options on the table to reduce those impacts. You can set lower charges for low-income groups. You can use congestion charges to replace vehicle registration fees (a flat tax, no matter how much or little you drive).

Low-income groups are actually far more likely to be taking public transport than driving; you can combine a congestion charge with improvements to public transport, making the transport system fairer and greener.

A recent study suggests that in the long term, people will return to public transport, just as they did after SARS and 9/11.

But when that happens, do we want to return to “business as usual” traffic congestion? Or would we rather see a fairer system where people who use the roads at their busiest pay more than people who use the roads less often?