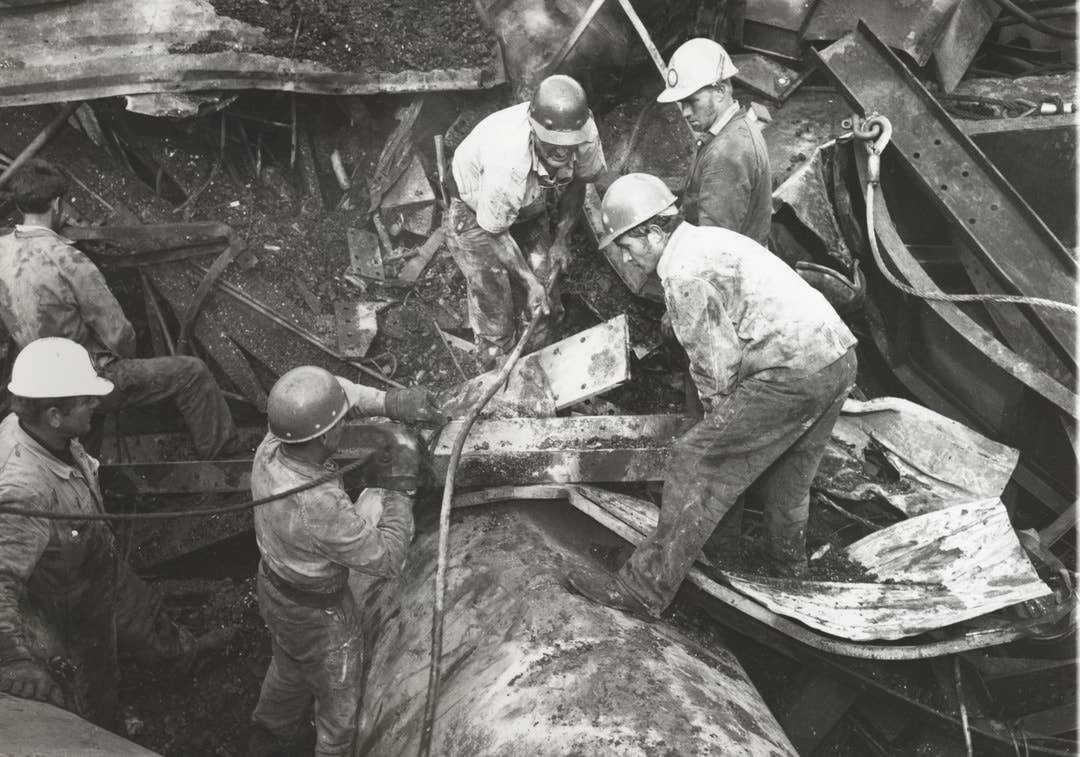

Fifty years ago, on 15 October, 1970, at 11.50am, 2000 tonnes of concrete and steel on the West Gate Bridge site buckled and crashed to the ground; 35 men died. It remains Australia’s worst construction disaster.

A visibly shaken Victorian premier, Henry Bolte, announced a royal commission. The investigation prompted worker safety reforms, and led to better ways of building steel box girder bridges.

But not all the lessons from the disaster have been learned, says structural engineer Associate Professor Colin Caprani of Monash University, who's also a director of the non-profit Confidential Reporting on Structural Safety Australasia (CROSS-AUS).

The West Gate was one of five steel box girder bridges that failed between 1969 and 1973. Three were being built in Germany, where engineers were replacing bridges destroyed in World War II. And one fell in Wales, when a 61-metre span over the River Cleddau collapsed on 2 June, 1970 – just four months before the West Gate – claiming the lives of four men.

Read more: Bridge maintenance is expensive, but delaying can be costlier

More more people died in Australia than elsewhere, and civil engineers from Monash University contributed to the royal commission’s technical understanding of what had gone wrong. The Monash team was led by Professor Noel Murray, the University’s founding head of the Department of Civil Engineering. Remnants from the collapse that were used in the research are on display in the University’s West Gate Garden.

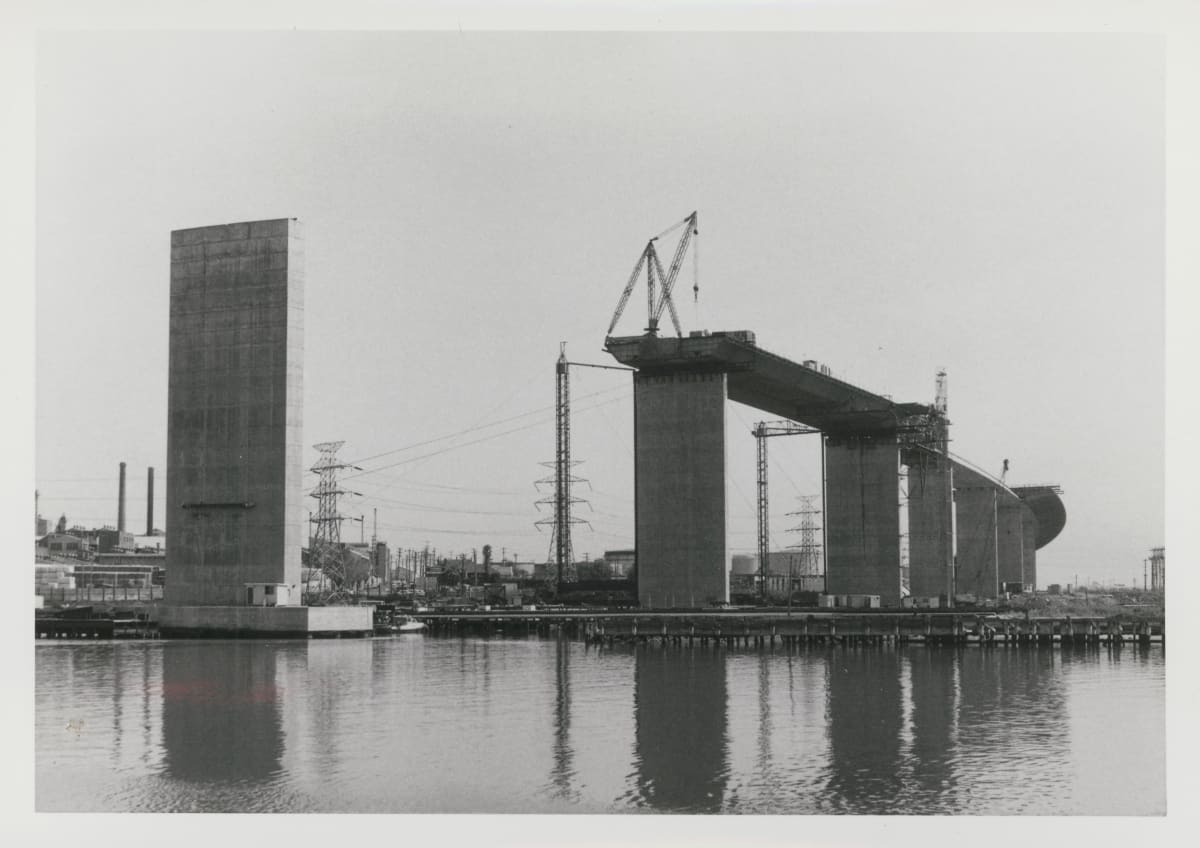

Chris Powell, who recently retired as the resources manager in the Department of Civil Engineering, was involved in Monash’s research after the collapse. Box girder bridges involve fitting together pre-fabricated segments. Some were floated on barges, then lifted in place by cranes. In 1970, the two sides of the bridge met in the middle – but one side was 11 centimetres higher than the other.

One attempt to correct the misalignment involved placing 10, eight-tonne concrete blocks on the higher side to push it lower. This caused the segment to buckle, which engineers tried to correct by removing bolts.

“Warning bells should have been rung,” Powell says. “They saw signs of this coming on.” Survivors said they felt movement on the bridge in the days before the span fell. “They went too far; they had committed themselves,” says Mr Powell.

He recalls the incident as “surreal, a moment when immense energy was released, followed by devastation, death and dying”.

“The people that survived have been traumatised for their whole life,” he says.

Part of Professor Murray’s investigations involved simulating the challenging conditions experienced in the bridge’s construction, with the help of the structural laboratory’s strong floor (now known as the Noel Murray strong floor). The floor is 1.5 metres thick and is the largest strong floor in Australia. It's used to test very high loading conditions, fatigue, impact and other stresses.

Lessons learnt, and not

Associate Professor Caprani says technical lessons from the West Gate Bridge collapse have led to the development of superior steel box girders – they're now used to construct some of the longest bridges in the world.

Worker safety has also improved enormously. In 1970, riggers on the bridge wore no harnesses, and welders protected themselves with shields made from asbestos. Victoria’s occupational health and safety legislation was introduced in 1985 – it included measures that were adopted when rebuilding began on the bridge. In the years after the catastrophe, construction unions campaigned for safer conditions.

But Associate Professor Caprani is concerned that after 50 years, other important lessons from the disaster are not being implemented.

“What happened around the collapse was a sequence of miscommunications or bad inspections and bad reporting between the different parties that were involved in the construction and the design and the inspection of the bridge,” he says. These “systemic issues” are resurfacing on modern construction projects, he says.

“There were workers underneath the bridge at the time that something strange was happening up on top, because there wasn’t good communication,” he says. “That hasn’t improved significantly. If we look at things like the Opal Tower in Sydney, the construction industry still has a way to go in learning the lessons of the West Gate Bridge collapse.”

Post-Grenfell report foresaw problems

In February 2018, the Building Confidence report into compliance and enforcement systems in the Australian construction industry was published. It was commissioned by Australia’s Building Ministers' Forum after London’s Grenfell tower fire tragedy in June 2017, in which 72 people died.

The Australian report, by Professor Peter Shergold and lawyer Bronwyn Weir, foresaw that problems were likely in this country, too. Ten months after Building Confidence was published, cracks in the Opal Tower led to 3000 residents being evacuated.

“What happened around the collapse was a sequence of miscommunications or bad inspections and bad reporting between the different parties that were involved in the construction and the design and the inspection of the bridge.”

The Building Confidence executive summary says “on occasion, builders improvise, making decisions on matters which affect safety without independent oversight”.

Associate Professor Caprani points out that the royal commission into the West Gate Bridge collapse found the tragedy was “closely related to the failure to make adequate inspections”.

“Are we doing adequate inspections today on large structures?” he asks. “Clearly, we’re not. The royal commission also mentions ‘failure to insist upon proper detailed periodical reports from the joint consultants’. Are we doing that properly today? Again, the evidence suggests we’re not.”

How worried should we be?

Since Building Confidence was published, “you have seen legislation for the registration of engineers in Victoria go through, and draft legislation for the registration of engineers in NSW as well”, he says. “So, things are beginning to happen. But when you ask, ‘Have we learnt the lessons from the West Gate Bridge collapse?’, I would have to say, in total, no.”

Large public infrastructure projects are subject “to much better third-party reviews” than private developments, Associate Professor Caprani acknowledges. According to his rough calculations, “the chance of being killed in a bridge collapse is far less than being struck by lightning”. But he draws a distinction between new bridges and older structures.

“The funding that’s going to the maintenance of all of our existing bridges is dwindling, just as those bridges are at the end of their design lives.”

He's concerned that the possibility of danger is downplayed.

“The attitude is, ‘Oh, these things have been fine for the last 50 years, they’ll be fine for another 50’.

“But you've got to say, ‘Super, we got 50 years out of them. That means that we really have to do something now.'

“We have to be vigilant. It’s becoming an increasing issue for countries that built everything 50 or 60 or 70 years ago, and haven’t been keeping on top of the maintenance since then.”