Australia's climate future, as outlined in Australia’s National Climate Risk Assessment report, is one of more extremes – more intense tropical cyclones, severe and more frequent heatwaves and flooding, and hotter, drier conditions that elevate fire risks.

This means that in climate change scenarios, energy and building efficiency will be even more essential for providing access to cool spaces and reliable power through weather-related extremes and disruptions.

However, new research released today shows that not everyone has equal access to this lifeline.

SFL: Understanding everyday energy use

As part of the Scenarios for Future Living (SFL) project, a RACE (Reliable Affordable Clean Energy) for 2030 Cooperative Research Centre project that aims to anticipate future household needs in Australia’s energy transition, we surveyed more than 5000 households.

The nationally representative survey investigates how emerging social trends, changing lifestyles and evolving household routines are shaping the way Australians live with technology and the potential implications for future energy demand.

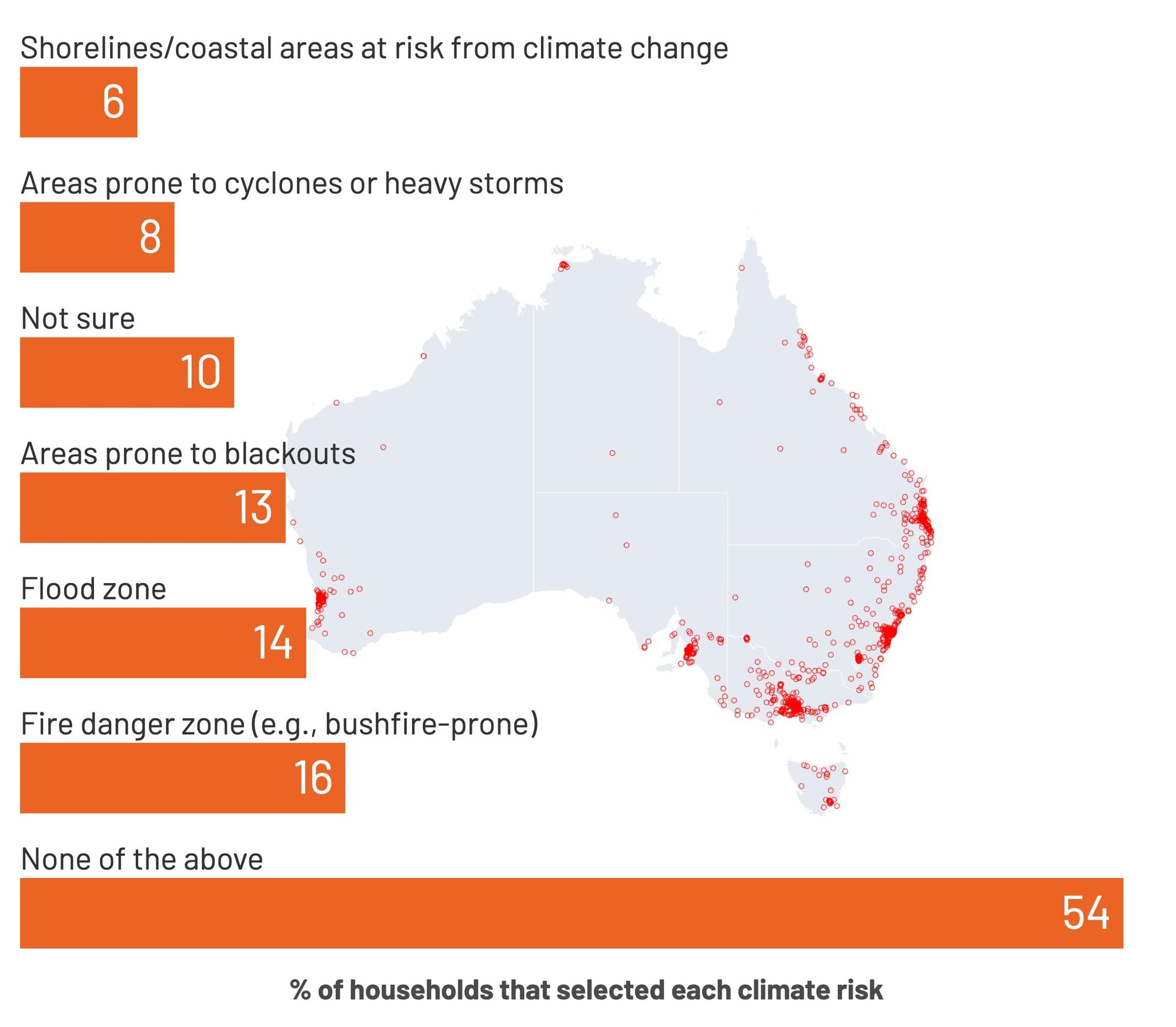

We found that 36% of Australian households report living in an area where their home is vulnerable to at least one climate-related risk (that is, cyclones, fire danger zones, floods, coastal erosion, or blackouts).

These households also experience energy-related hardship at nearly double the rate of those not reporting climate risk.

As climate change intensifies, energy hardship will compound the impacts associated with living in climate-risk areas, while extreme weather events, technology disparities and rising energy costs will increase the breadth of affected communities.

Treating energy equity and climate adaptation separately risks deepening issues associated with a lack of access to adequate, affordable and reliable energy, leaving behind the most vulnerable households.

Weak points in household resilience

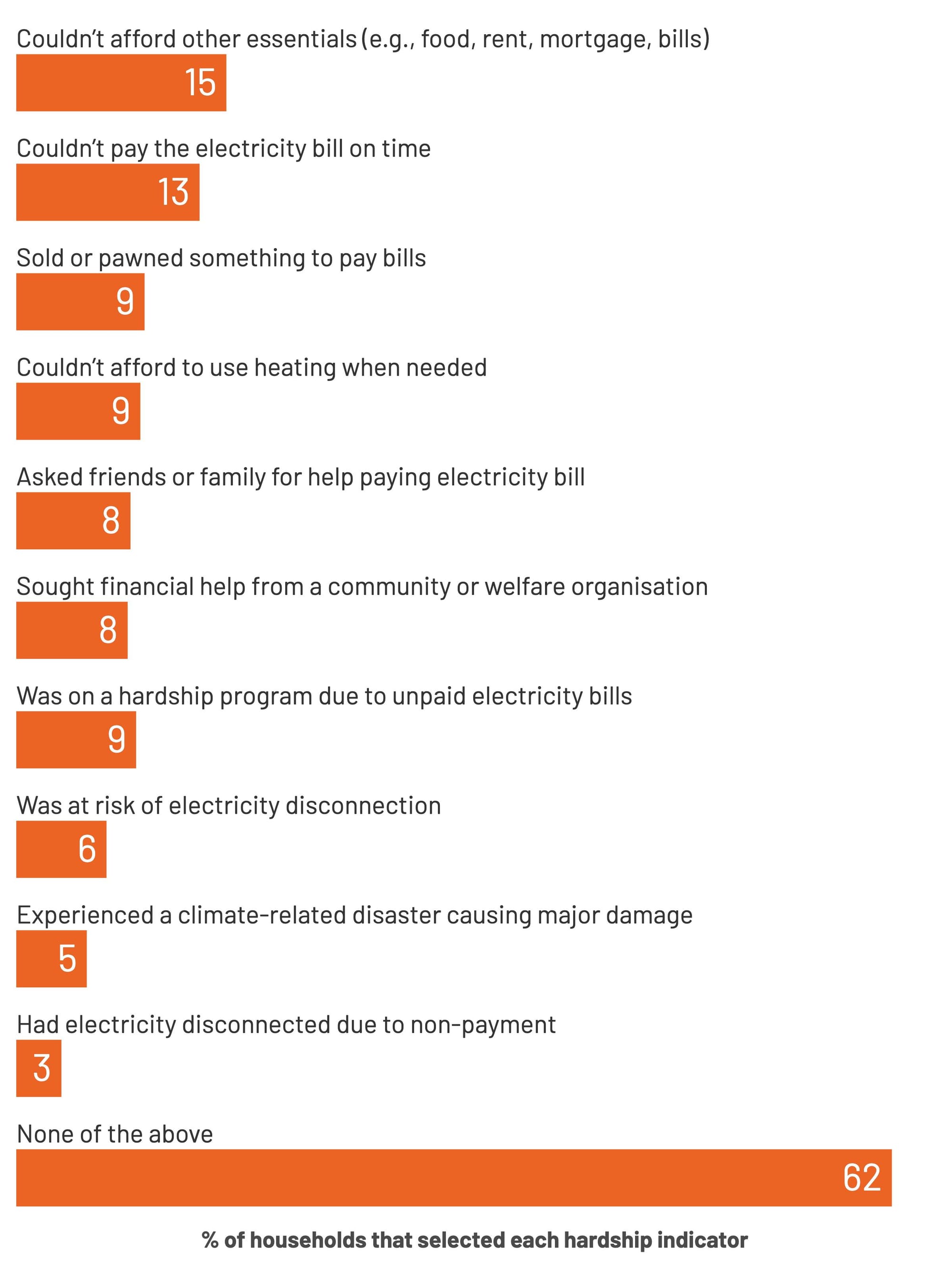

More than one in three households (38%) reported experiencing at least one form of energy-related hardship in the past year.

Some couldn’t pay electricity bills on time (13%). Others couldn’t afford to heat their homes (9%) or had to sacrifice essentials such as food or housing (15%) to meet energy costs. Many sought help from family or community organisations (8%) or entered hardship programs (9%).

Lower-income households and younger age-groups were more likely to report experiencing hardship.

Renters reported higher levels of energy-related hardship (50%) than households with a mortgage (34%). Even middle-income mortgage-holders weren’t immune, as rising housing and energy costs intersected.

For instance, at lower incomes, renters dominated hardship, reflecting well-known vulnerabilities regarding affordability, insecure housing and limited ability to make energy efficiency improvements. At middle to higher incomes, however, hardship wasn’t confined to renters.

This points to how energy stress can be linked to broader mortgage or housing cost stress, affecting middle-income households just as much as low-income renters.

Cool spaces may become harder to access

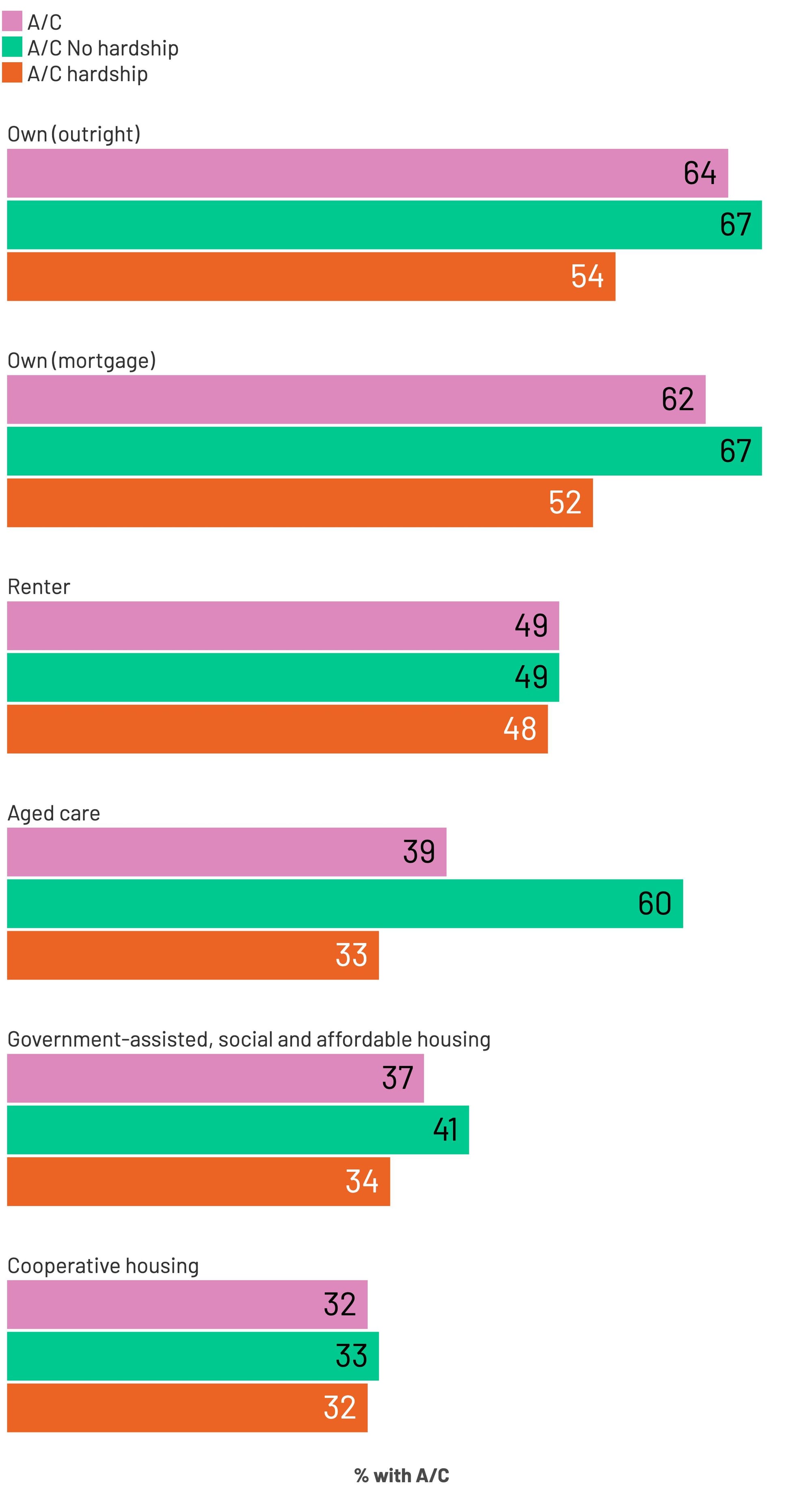

Nearly half of Australian households (44%) reported having no air-conditioning. Ownership rates diverged sharply across groups – only 49% of renters and 37% of social housing residents had AC, compared with 64% of homeowners.

Households already experiencing hardship or climate risk were less likely to have cooling and therefore more exposed to heat-related health risks.

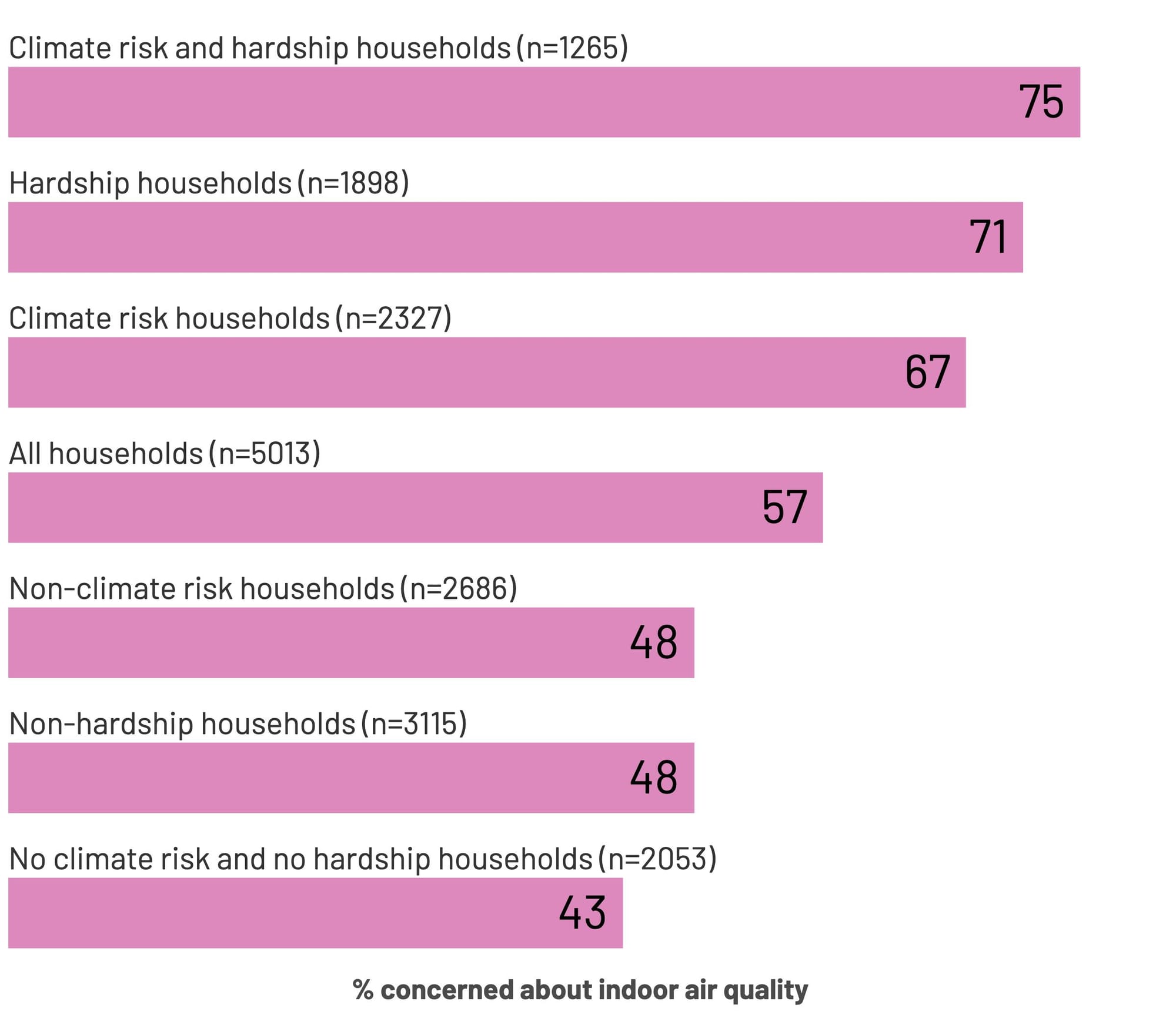

Indoor air quality also emerged as a significant concern.

While 57% of households worried about the air inside their homes, that number rose to 71% among those in hardship and 75% among those facing both hardship and climate risk.

These households cited worries about smoke, mould and dampness, issues likely to worsen with climate change.

In short, the households with the greatest health and wellbeing risks are the least likely to have the technologies or resources to have access to healthy air at home.

Building resilience through equity

Policies that promote electrification, renewable energy and demand flexibility must also ensure that every household can participate safely and affordably.

Structural barriers such as tenure insecurity, limited retrofit authority and income constraints restrict access to solutions such as insulation, double-glazing or efficient cooling.

Without intervention, access to healthy, safe and comfortable air will increasingly become a marker of inequality under changing climate conditions.

Read more: How energy-efficient homes can make us healthier and safer

Published in a series of reports, the findings from our survey provide policymakers, regulators and industry with new evidence to anticipate future energy challenges and design fairer, more resilient systems.

In a changing climate, the right to breathe clean air and to stay cool in dangerous heat shouldn’t depend on what you earn or where you live.

Resilience needs to come from communities and systems that keep everyone safe and cool, not just from those who can afford or have access to technological solutions.

The authors of this article acknowledge the broader Scenarios for Future Living research team. SFL is a project funded by the RACE for 2030 CRC in collaboration with industry partners Ausgrid, Citipower/Powercor/United Energy, Red Energy, NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, VIC Department of Energy, Environment, and Climate Action, and research partners Monash University, University of New South Wales, University of Technology Sydney, and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

We extend our gratitude to all of the research participants who have taken part in the SFL project.