On an international scale, COP27 is being described as a disappointment. Despite some wins in the “loss and damage” space, COP27 has failed to act on mitigation and emissions reductions.

Being a young person at COP27 is a bizarre experience. On the one hand I felt overwhelming gratitude – experiencing COP is a privilege, and is genuinely life-changing.

Yet on the other, I felt utter devastation. Spending each day walking between panel events made it clear that climate change is already destroying communities worldwide.

For me, this duality was most clear when having conversations with those whose voices are usually marginalised.

Hearing their stories was consistently anxiety-inducing. I want to highlight some of these marginalised voices so you, too, can learn what these communities face, and why inclusion of their voices matters.

Indigenous communities

We spoke to some indigenous leaders from Guyana who told us it took them six days to get to COP27. They told us they undertook this journey because their communities are suffering at the forefront of climate change.

This was a consistent theme throughout my time at COP27.

I spent a lot of time listening to indigenous leaders from the Pacific and the Torres Strait. Despite their homes being at risk of total devastation, they still show so much strength. Their willingness to retell their stories of trauma in an effort to get the world to act on climate change is nothing short of heroic.

Yet, their frustration is clear. These leaders have been at the forefront of the fight for climate action for decades. Their stories and their knowledge hold the solutions the world needs, yet their voices are almost always left on the margin.

Further, in many places, poverty is more common in indigenous communities compared to the rest of the population. This matters, because these big climate conferences can be expensive. It’s not just flights, accommodation and food –it’s one to two weeks spent away from work or education.

This is something that many people can’t afford. Hence, those on the margins are often unable to contribute to these summits.

The LGBTQIA+ community

This COP27 was a weird one for queer folks. From what I learnt, there’s usually quite a large, visible LGBT presence at COPs. But this year, the community was silenced.

This marginalisation, in combination with the silencing of LGBT people at this year’s FIFA World Cup, has made this community feel shunned.

This is important, as climate change often impacts queer people disproportionately.

I heard one panellist speak about LGBT experiences in developing nations. They described that some trans people feel safer to risk their lives during natural disasters, and stay in their homes rather than go to the disaster shelters.

This community is fighting for a better future for all, yet its members were made to hide themselves at COP27.

The disabled community

The disabled community experiences climate change intensely. Often, evacuation and rescue plans don’t consider disabilities, and so members of this community are left in danger.

Yet, I learnt that COP and other international processes are inaccessible to many in the community. Small things such as uneven surfaces at COP27 made me, an able-bodied person, trip over daily.

But this inconvenience for me is a danger for others, and makes participating at COP difficult.

Even in intersectional climate spaces, the disabled community is often minimally talked about. Protests are often seen as the pinnacle of climate activism, yet these spaces are also inaccessible.

But this community also wants people to not think of them as always vulnerable. They’re not passive victims; rather, they have no choice to be agents of change.

Women dominate, yet...

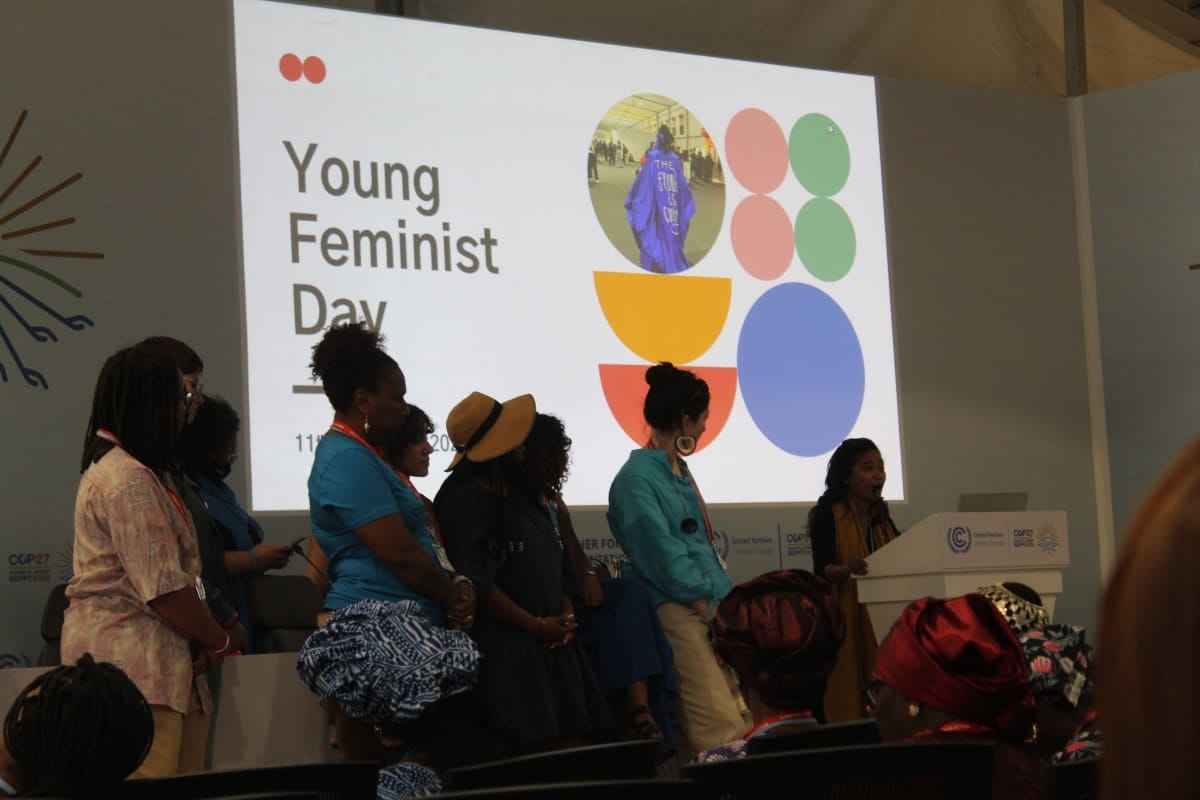

I spent almost all my time at COP within civil society spaces. These are dominated by women and feminine presenters. Hence, it was shocking to me to read that the party delegations at COP27 were 63% male to 37% female (with others not even being considered in the count).

Women and feminine people are at the forefront of this fight, because they’re at the forefront of climate change.

In most countries, gender norms put women in positions where they have to cook and clean. They look after their families, and so they’re acutely aware when there are food or water shortages.

Domestic violence against women and girls is increasing as a direct result of climate change as famine and disease cause tensions internationally.

But with a majority of party delegates being “male”, it’s clear who’s still calling the shots. Hence, there’s still an ugly, patriarchal disconnect between those making the rules and those who have to experience the consequences of them.

The youth factor

I attended a panel discussion where my friend (a youth climate activist) was publicly talked down to by a government official from their own country.

While many countries claim to listen to youth, in reality, many still see us as children. Organisations and countries will “youthwash”, and pretend they’re acting on climate change to genuinely protect future generations, but in reality, their authenticity only goes so far.

And “youthwashing” isn’t a fickle issue. Youth today are the most educated and well-connected generation to have existed. We’re also the generations that are going to still be alive when the climate crisis devastates our world.

No child should have to worry about their future. But this worry means young people have no choice but to be radical and creative.

We have the solutions – we’re not naive. If leaders listen to us, we’d be able to progress to a world where the future is no longer in jeopardy.

The ways we differ are small, yet are treated as if they’re big. These communities are made of people who are suffering the consequences of climate change now. They hold the solutions the world needs, but the systems we have are marginalising them.

If you’re an ally of any of these communities, your role needs to be actively working against these systems to ensure their voices are centralised.

If we want to keep 1.5°C alive, this is no longer a time where we can rely on individual action. Now is the time to speak out and be an ally for them.