New collaborative work at an Aboriginal cave in eastern Victoria, recently published, shows the stark difference between contemporary archaeological research and that conducted in the 1970s.

In 1971, Cloggs Cave was rediscovered near the town of Buchan in East Gippsland, Victoria. By the end of 1972, archaeological excavations had been completed in the cave and adjacent rock shelter. The findings – extinct giant kangaroo remains (megafauna), Aboriginal stone tools dating back to the last Ice Age, and buried fireplaces – made national news at the time.

Cloggs Cave belongs to the Krauatungalung clan of the GunaiKurnai nation. However, in the 1970s, neither state and federal agencies, nor most of Australian society, acknowledged traditional owners’ rights to authorise and oversee research into their cultural places.

Of habitats and diets

Five decades ago, archaeological research and radiocarbon dating were in their infancy. Researchers were racing to find the oldest Aboriginal sites across Australia. Non-Indigenous archaeologists determined what research questions to ask, and controlled how the research was conducted and interpreted. Findings often focused on how Aboriginal people had responded to their environments, and what they ate.

The first stories written about Cloggs Cave in the mid-1970s described it as an Ice Age refuge from which local plant and animal resources were exploited.

According to these early interpretations, people had left the cave to inhabit the rock shelter outside as the climate warmed, around 10,000 years ago.

GunaiKurnai-led research, 50 years later

The GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation revisited Cloggs Cave in the years leading up to 2019. It found sediments were eroding from the walls of the largest 1970s excavation pit. Although the pit had been shored up, the extra support was removed in the 1990s.

GunaiKurnai cultural heritage workers sought to use new technologies to revisit the original findings. Importantly, this research would now include GunaiKurnai cultural knowledge passed down from generation to generation.

Researchers from Monash University, the Université Savoie Mont Blanc (France) and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage were invited to be project partners.

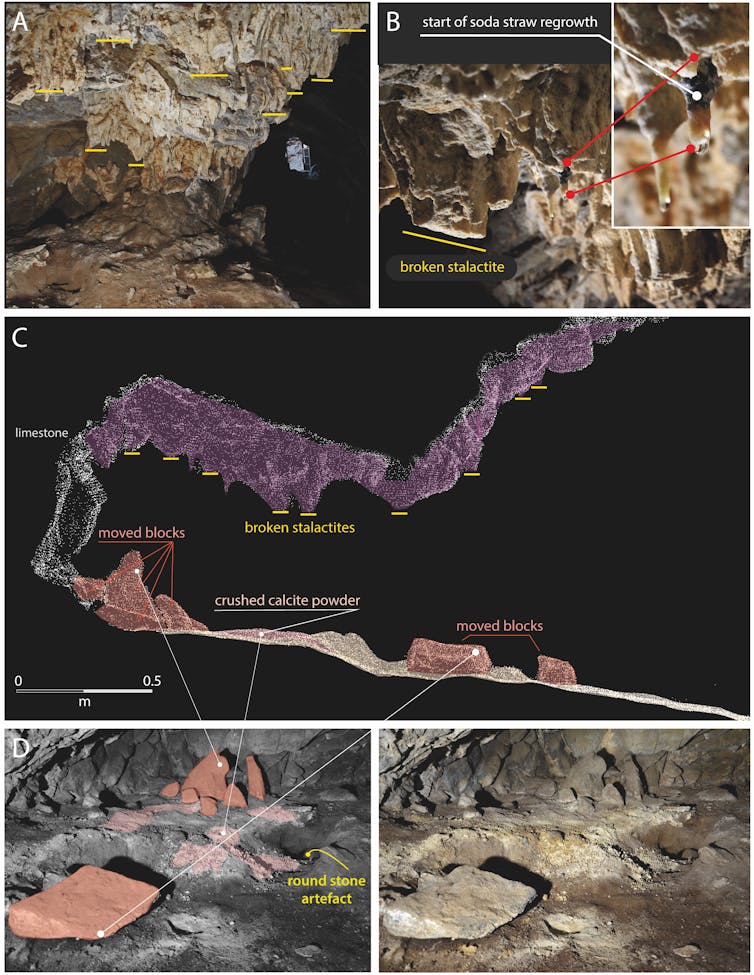

In 2019, the cave was mapped in detail using a 3D light detection and ranging scanner, and a drone. New excavations of sections of the floor were conducted, and the chronology of people and megafauna in the cave was investigated using radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence dating techniques.

The investigations yielded fascinating insights about how the people inhabited the cave thousands of years ago. In a small alcove at the back lay a stone arrangement, including a layer of crushed minerals. Most of the stalactites on the ceiling had been intentionally broken. Uranium-series dating of parts of the regrown stalactites revealed these mineral deposits were first broken by Aboriginal people more than 23,000 years ago.

Towards the cave’s entrance, the new excavations uncovered a buried standing stone surrounded by fires lit 2000 to 1600 years ago, and hundreds of thousands of animal bones. The animals’ deaths were natural – so Aboriginal people had not come to the cave to eat or cook food.

GunaiKurnai worldviews

Since the 1970s, Australian society has changed, with an increased recognition of Aboriginal cultures, knowledges, and land rights. It's now possible for the traditional owners to finally have a say in the story of Cloggs Cave, and in GunaiKurnai history.

The contrast in the stories from the two archaeological projects, 50 years apart, could not be starker.

According to GunaiKurnai traditional owners – and Aboriginal perspectives recorded in the mid-19th century – caves are spiritually important. In 1875, Aboriginal men Turnmile and Bunjil Bottle showed Alfred W. Howitt the “Den of Nargun” in Gippsland. Howitt wrote that this rock shelter was home to “a mysterious creature which they believe haunts these mountains where they were living in caves and holes”.

Read more: Recovered Aboriginal songs offer clues to 19th-century mystery of the shipwrecked 'white woman'

Stories told early last century by residents at Lake Tyers Mission (now known as the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Trust) described fearful beings called nargun, who lived in caves.

Caves were also frequented by magical practitioners called mulla-mullung. They trained and practised their magic, using crystals and other stones, and ground powders such as ash.

This information was not considered by archaeologists in the 1970s, as it didn't fit their (mainly secular) interpretations in terms of habitat and diet. What was missing was a deep understanding that the rich social, cultural, and ritual lives of Aboriginal people could fundamentally shape the archaeological record. They did not simply respond to their environments.

A new picture of Cloggs Cave now emerges. The cave wasn't just a refuge from a cold environment, but a theatre of culturally rich, social and magical activities dating back millenia. It was avoided by people for day-to-day living, and probably used by GunaiKurnai mulla-mullung.

What was located during the 2019 research had been there all along, but wasn't noticed by previous researchers.

This is partly because new techniques give us a better window into the past activities of Aboriginal people at the cave. These new ways of seeing are matched with new ways of listening and researching – transforming how we tell archaeological histories.

Read more: Connection to Country: Teaching science from an Indigenous perspective

The authors of this article, who also include Jean-Jacques Delannoy and Russell Mullett, are just five of the 19 authors of the journal article. We thank the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation, Joanna Fresløv, Martin and Vicky Hanman of Buchan, and the nine Australian and international universities who collaborated on this project.

Bruno David receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Chris Urwin receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Jean-Jacques Delannoy receives funding from the Centre National Recherche Scientifique (France) – Ministère de la Culture (France)

Lynette Russell receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Russell Mullett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.