The race to net zero is accelerating. Recently, US President Joe Biden and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese unveiled a climate pact to boost cooperation. The move signifies Australia is becoming a global leader in the renewable energy rollout and critical mineral supply.

Australia’s rich iron ore deposits and cheap solar offer yet another way we can lead. If we locate green hydrogen plants near green steel facilities, we can shift the highly polluting steel industry away from fossil fuels.

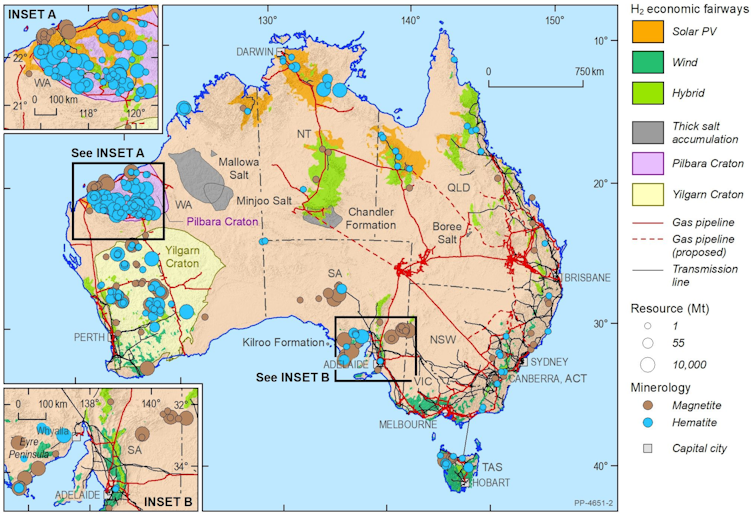

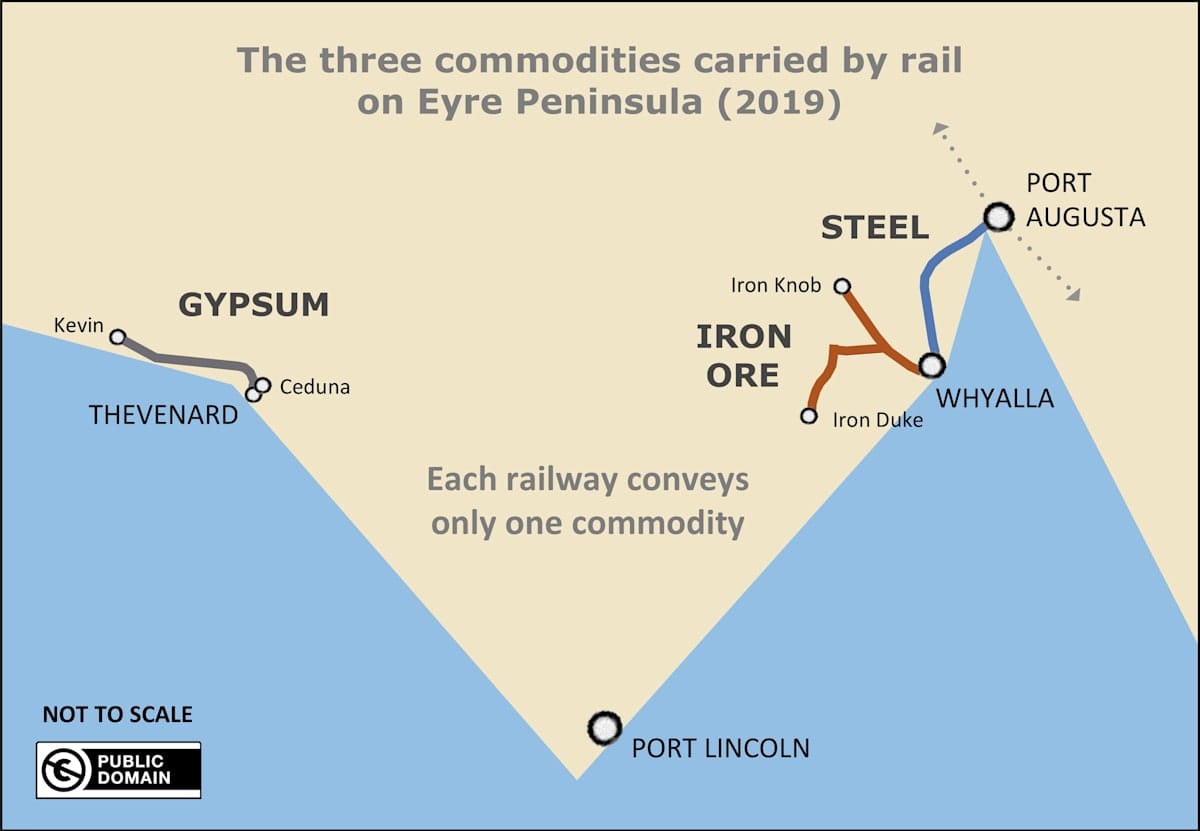

Our new research shows co-locating plants in sun-rich, iron-rich places such as Western Australia’s Pilbara and South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula can help overcome the “first mover problem” for green hydrogen – you can’t have a hydrogen industry without buyers for it, and you can’t have buyers without hydrogen.

How it would work

Cheap solar power would be used to crack water into hydrogen and oxygen. This green hydrogen would be piped a short distance to a green steel plant, which uses hydrogen and electricity to produce iron from the ore, and then an electric arc furnace to smelt steel.

As we grapple with ways to decarbonise the steel sector, which uses 8% of the world’s energy and produces 7% of all energy-related carbon emissions, we should urgently look for opportunities like this. As a bonus, cheap power from solar and wind could make Australian-made iron and steel more competitive globally.

Why is Australia so well-placed?

We’re the world’s largest iron ore exporter. Under our red dirt lies an estimated 56 billion tonnes of iron ore, as of 2021. Export earnings reached A$133 billion in 2021-22. We also profit from the current emissions-heavy way of making steel, by exporting $72 billion worth of metallurgical coal.

Australia’s potential as a green hydrogen provider is often promoted. This year’s federal budget allocated $2 billion to help make it a reality. But our distance from the rest of the world makes pipelines prohibitively expensive, and shipping hydrogen is difficult.

Read more: Cooperation with the US could drive Australia’s clean energy shift – but we must act fast

One solution is to use it here. Green hydrogen could make it possible to onshore more iron and steel production.

Clean steelmaking will bring major change to our iron ore exports if other countries take it up. Traditionally, 96% of our exports are the most common type of ore, hematite. But this is currently not suited to green steelmaking.

By contrast, magnetite ore only accounts for 4% of exports, but can be used in hydrogen-based green steelmaking.

Australia has vast reserves of magnetite ore, which previously hasn’t been in as much demand. But these ore bodies will become valuable under the right economic conditions.

And while we can solve steel’s carbon problem with much better recycling of this valuable material, we’ll still need new steel equivalent to about 50% of the current rate of production in 2050, due to issues with converting scrap to reusable steel and removing contaminants.

Where should we co-locate these plants?

Major iron ore centres in the Pilbara and Eyre Peninsula already have ports, a workforce and other infrastructure. That makes them the logical first choice to co-locate solar, wind and hydrogen with iron and steelmaking.

We modelled what would happen if these sites expanded wind and solar power to make hydrogen, and found the cost of green steel could drop substantially to about $900 per tonne by 2030, and $750 per tonne by 2050.

By exporting green iron and steel, Australia could boost trade value, reduce global greenhouse emissions, and link our exports with global decarbonisation efforts. Steel will become even more important given it’s so vital to manufacturing solar and wind.

Our recent modelling has found key benefits in linking hydrogen hubs and future iron ore operations.

First, it avoids the problem of transporting hydrogen, which, especially in liquid form, can be expensive and energy-intensive to move.

And second, co-locating green hydrogen gives an immediate boost to the industry. At present, green hydrogen is at the early stage before increased scale and knowledge drives costs down.

To compete with coking coal, green hydrogen must get cheaper. Part of this will come from falling renewable energy prices, better electrolysers to make hydrogen, and carbon pricing. But part of it will be locating hydrogen production where it can be used.

Choosing a site is the most important consideration. While access to infrastructure and cheap ore are important, the cost of green steel largely depends on low-cost hydrogen and cheap renewables.

Australia’s state and federal governments are backing hydrogen as an industry of the future. To go from paper to reality will require policy incentives, low-interest loans, research and development funding, and investment in infrastructure.

Policies to boost renewable energy and develop the hydrogen economy will create a more conducive environment for green steel production.

If we combine our wealth of solar, hydrogen, and iron ore, we can help make global steel production green, and also create the conditions for a green hydrogen export industry.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation, and was co-authored with Andrew Feitz, Marcus Haynes and Zhehan Weng, from Geosciences Australia.