The recent energy crisis – fuelled by Russia’s war on Ukraine – has highlighted the interdependence and fragility of the world’s energy system, and the importance of trading energy between regions of the world.

As the world decarbonises, the dynamics of energy trading will change dramatically.

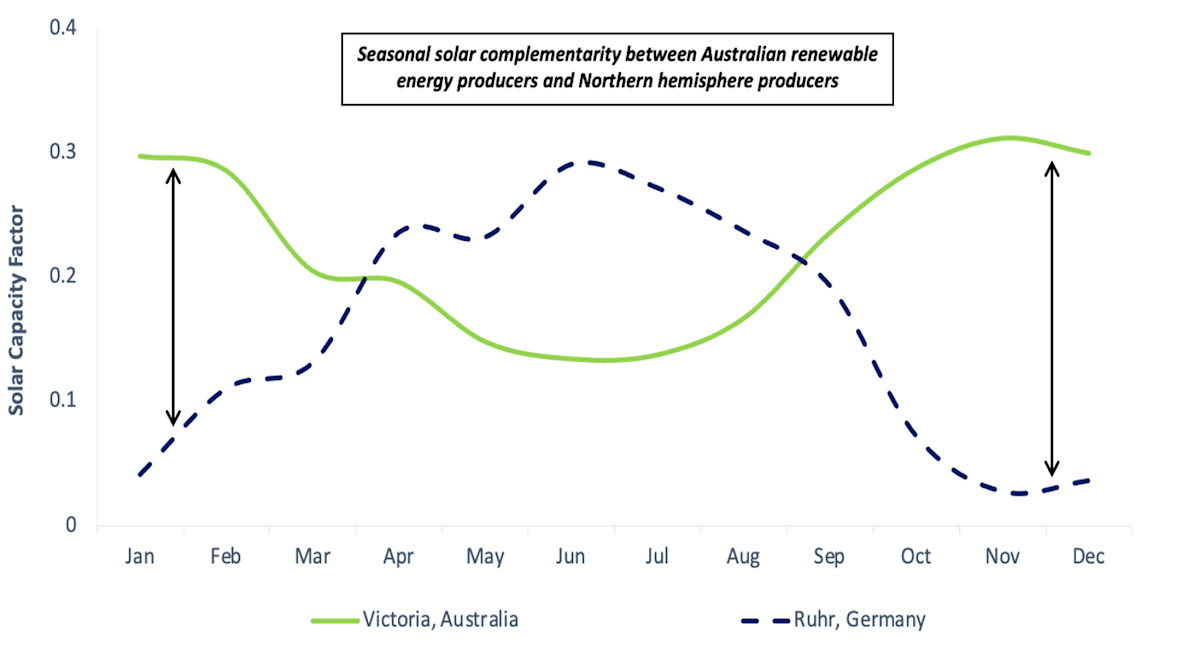

One part of the problem is the seasonality of energy demand and the potential for generating power in different parts of the world. For example, the northern hemisphere experiences an increased demand for energy in winter (December-February), which is the same time solar energy production in the southern hemisphere is at its maximum – our summer.

A few years ago, the idea of running an HVDC cable from Darwin to Singapore to supply renewable electricity was deemed “insane” but made sense by Sun Cable chairman Mike Cannon-Brookes.

Likewise, the idea of shipping renewable ammonia from the Pilbara to Germany to meet its energy needs was considered something for the distant future.

And yet now some of the biggest companies in the world are racing to invest in large multi-gigawatt-scale renewable energy and renewable hydrogen projects in Australia, and are actively exploring the potential for international trade in hydrogen, green fuels, and ammonia.

Why the rush?

The world needs to at least halve its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to keep global warming as close as possible to the Paris target of a 1.5°C increase.

Although many scientists say that this is impossible to achieve given the carbon lock-in so far, it gives us an idea of the scope of the transformation that must be undertaken urgently.

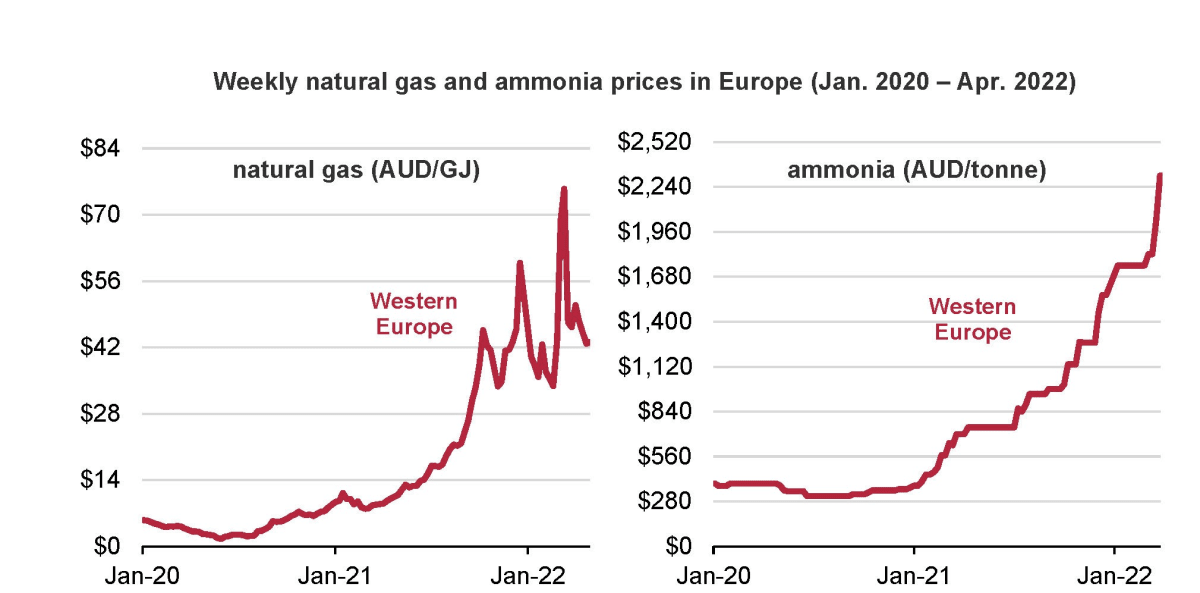

At the same time, the IEA notes that power prices in many European markets in the first half of 2022 reached three to four times as high as they were in the first half of 2016 to 2022.

The cost of fossil gas and coal prices have skyrocketed around the world, including in Australia. These rising fossil fuel costs are flowing onto major commodities, including ammonia.

Ammonia, a vital commodity for the world’s supply of fertiliser, topped US$1600 a tonne (about A$2240 a tonne, an all-time high) in May 2022. This follows an 80% surge the previous year, making ammonia made from renewable energy increasingly competitive.

Our modelling shows a levelised cost of renewable ammonia of A$756/tonne and A$659/tonne in 2025 and 2030, respectively, at Australian hydrogen hubs.

Based on these results, by 2030 green ammonia made from renewables would be cost-competitive with fossil fuel-based ammonia when gas prices exceed A$14/GJ. (For comparison, the current east coast wholesale gas price in Australia varies between A$15–20/GJ).

These findings would be further improved at some locations when the seasonal demand patterns of trading partners in the northern hemisphere are taken into account.

What is the significance of seasonality?

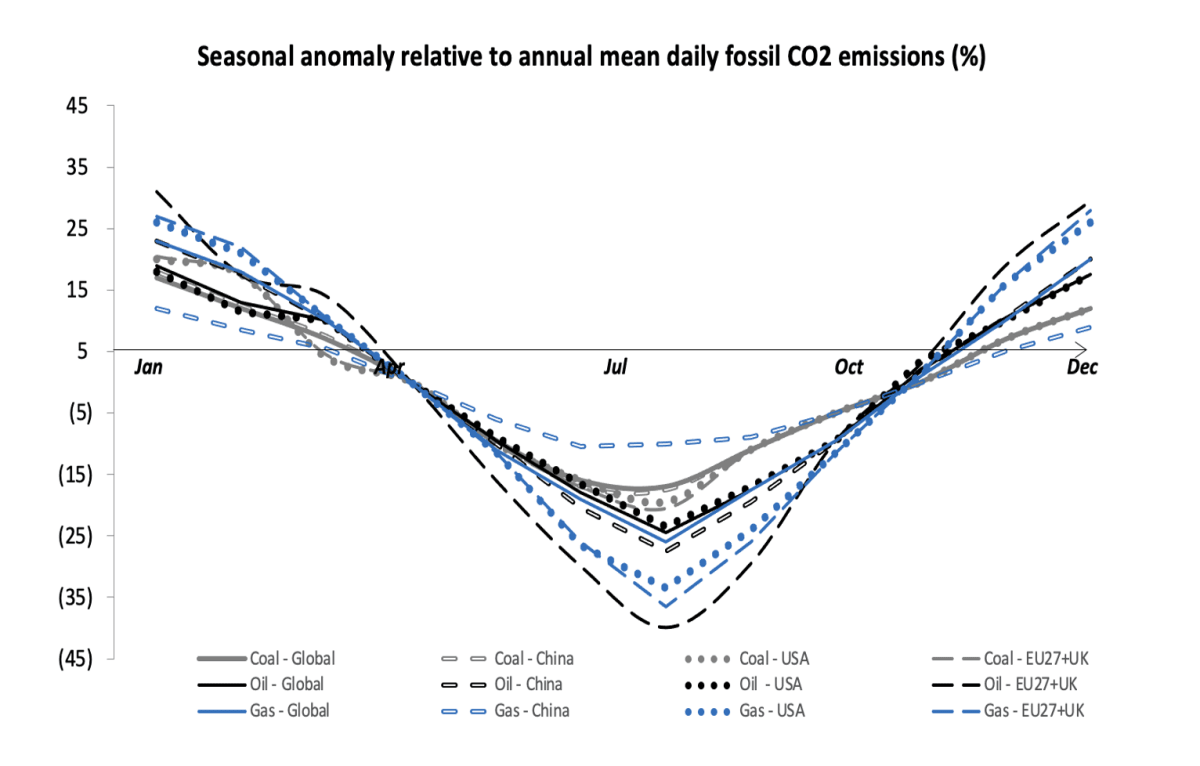

Global energy demands vary through the year, driven largely by the change in seasons in the northern hemisphere. This has profound implications for the production of green hydrogen and ammonia.

A critical aspect of meeting the world's energy needs in a decarbonised future is the end-use of renewable hydrogen and its temporal value, particularly for potential importers such as Germany.

The figure below shows the seasonal value to Germany of renewable ammonia produced in an area with comparable solar resources – Gippsland, Australia.

There’s a significant demand-supply mismatch in the northern hemisphere in winter, when local energy demand surges and renewable supply plunges. This large gap could be filled by Australian solar-powered ammonia, which peaks during that time.

We’ve compared the domestic use of coal and fossil gas reserves by a potential hydrogen importer along with their seasonal energy consumption patterns throughout the year.

The solar generation shortfall in winter implies a substantial hydrogen supply deficit using regional resources; however, this is when energy demand reaches its highest.

The demand side would need to compete for the limited resources in boreal winter, which would likely drive up energy commodity prices, including renewable hydrogen. Prioritising limited resources for social welfare will adversely affect the industrial sector.

To meet the enlarged demand-supply gap in winter, domestic producers in the northern hemisphere need to oversize their systems to produce additional hydrogen or ammonia in summer to be stored for winter use, which will significantly drive up overall production costs.

The temporal gap between domestic supply and consumption highlights the economic value of international imports at that time.

Australia’s seasonal advantage

Rather than investing in additional production capacity and storage, it could be more economical to seasonally boost Australia’s solar-made ammonia supply by directly shipping it to the trading partners while their demand peaks and local supply plummets in boreal winter.

In other words, Australia can take advantage of our seasonal competitiveness to export hydrogen to Europe when their demand is high and our generation capacity is also high. Seasonal complementarity will be mutually beneficial to energy and ammonia trading partners on opposite sides of the globe.

This article was co-authored with Scott Hamilton from the Smart Energy Council.