We're entering our first pink-tinged recession.

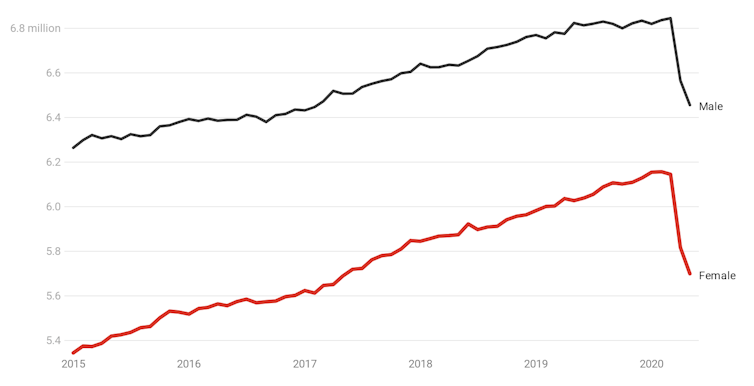

The official unemployment figures released last Thursday confirmed that female work has been more heavily impacted than male work.

Since February 457,517 women have lost their jobs, compared with 380,737 men.

The disparity is likely to be worse when JobKeeper ends. The jobs at risk are concentrated in female-dominated industries.

Employed Australians, total

This might be thought reason enough for the government to focus its recovery efforts on supporting female jobs rather than “shovel ready” male-dominated jobs such as those in the construction industry.

But there’s another reason.

Women report poorer mental health than men. When responding to Australia’s Household Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) survey, 20% of women report having diagnosed depression or anxiety, compared with 13% of men.

Young women suffer doubly

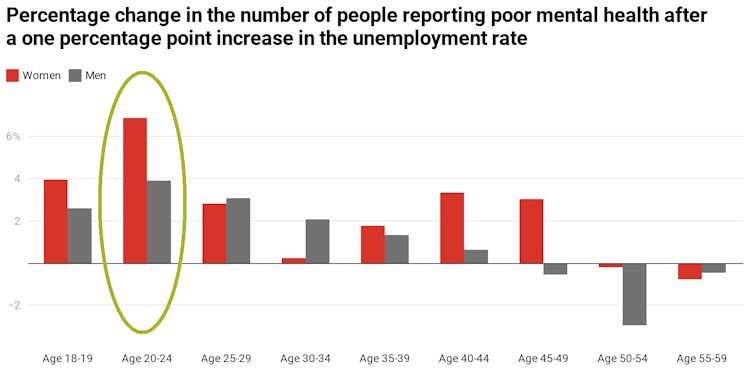

Using almost 20 years of HILDA data (2001-2018), we've compared changes in people’s mental health in locations that are experiencing increased unemployment with changes in other times and locations, controlling for other things that might affect mental health.

Women in their early 20s and mid-40s are more affected by local economic downturns than men.

These ages are the ones in which women’s involvement in the labour market is the highest – just before and after having children.

The graph below shows that for women in their early 20s, every one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate is estimated to increase the number of women with poor mental health by about 7%.

This suggests that an increase in the unemployment rate from about 5% in February to the peak of 10% forecast by the Reserve Bank could increase the number of young women with poor mental health by about 33%.

It would increase the number of young men with poor mental health by about 20%.

Searching for explanations

It might be that because women typically spend fewer active years in the labour market, the effect of unemployment in those years is more devastating.

A spell out of the workforce with children after a spell out of the workforce with unemployment means a woman who lost her job during a recession might never obtain the lifetime earnings she would have expected.

Further analysis of the HILDA data supports this contention. Among young women, the association between unemployment and poor mental health is much stronger for those that would like to have children.

Women in their mid-40s (who are often trying to re-enter the workforce after focusing on children) are also much more prone to poor mental health than men during downturns, perhaps because it’s their last chance to build lifetime earnings.

We need a two-pronged approach

Australia’s previous recession, in the early 1990s, hit the jobs of men much harder than those of women. This recession looks different. Women are being hurt more than men, and the effects on the mental health of women aged in their early 20s and early 40s will amplify the difference.

The right approach is to ensure recovery programs are directed towards industries that employ women, and to boost funding for mental healthcare, especially programs designed for women.

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System found it “failed to aid those who are most in need of high-quality treatment, care and support”.

It isn’t a good start.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.