In 2019 and 2020, remarkable Indigenous archaeology took place in the east of Victoria, in a cave in the foothills of the Australian Alps. The Snowy River flows nearby. The area, at Cloggs Cave near Buchan, is GunaiKurnai Country.

The researchers – from the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation, representing traditional owners, and Monash University – found two sticks each protruding from its own tiny fireplace deeply buried in a section of the cave.

They are no ordinary installations, each having significant cultural value. The team’s new paper, in the scientific journal Nature Human Behaviour, explains profound insights into the rich heritage of local Indigenous peoples 11,000 to 12,000 years ago in this isolated pocket of Australia’s southeast.

The paper also highlights how earlier research – which reduced local cave use to group shelter and the consumption of food – missed key cultural dimensions of how and why some people used caves, such as Cloggs Cave.

The researchers say this kind of work was done differently then, without consultation or permission from local Aboriginal traditional owners.

Aboriginal families were assumed to have lived in the caves. But researchers say this was a product of “subsistence thinking” prevalent in Australian archaeology at the time.

Now, it’s known that culture is much richer, and combining local community knowledge and research priorities with the latest scientific methods in community-driven research has now shed new details of the deep connections that GunaiKurnai have with their ancestral caves.

The new research was requested and co-led by the GunaiKurnai, with the ethical protocols for the research written into a memorandum of understanding, checked for ethical compliance and signed in 2018.

GunaiKurnai Elder Uncle Russell Mullett said the important factor was to:

“... establish the relationship, the trust, and the ability to bring a lot of people in to help to reinterpret this cave, and the journey.”

He says the 1970s approach to research, and the report that resulted from it, contained “misinformation or misinterpretation” of the findings. “Some things might be right,” he says, “but a lot of it wasn’t”.

He says the new dig is “remarkable”, and was done in a partnership between the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation and transdisciplinary academic researchers coordinated through the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre.

It revealed “cultural knowledge passed down through 500 generations”.

“… for these artefacts to survive is just amazing,” he says. “They’re telling us a story. They’ve been waiting here all this time for us to learn from them. A reminder that we are a living culture still connected to our ancient past. It’s a unique opportunity to be able to read the memoirs of our ancestors, and share that with our community.”

The paper explains that in societies without writing, archaeological evidence for ethnographically-known rituals have only rarely been documented over more than a few hundred years.

Since early colonial times in the 1840s – covering the period of GunaiKurnai ethnographic writings – GunaiKurnai caves were not used as everyday living places, but as “secluded retreats for the performance of rituals by Aboriginal medicine men and women known as ‘mulla-mullung’.”

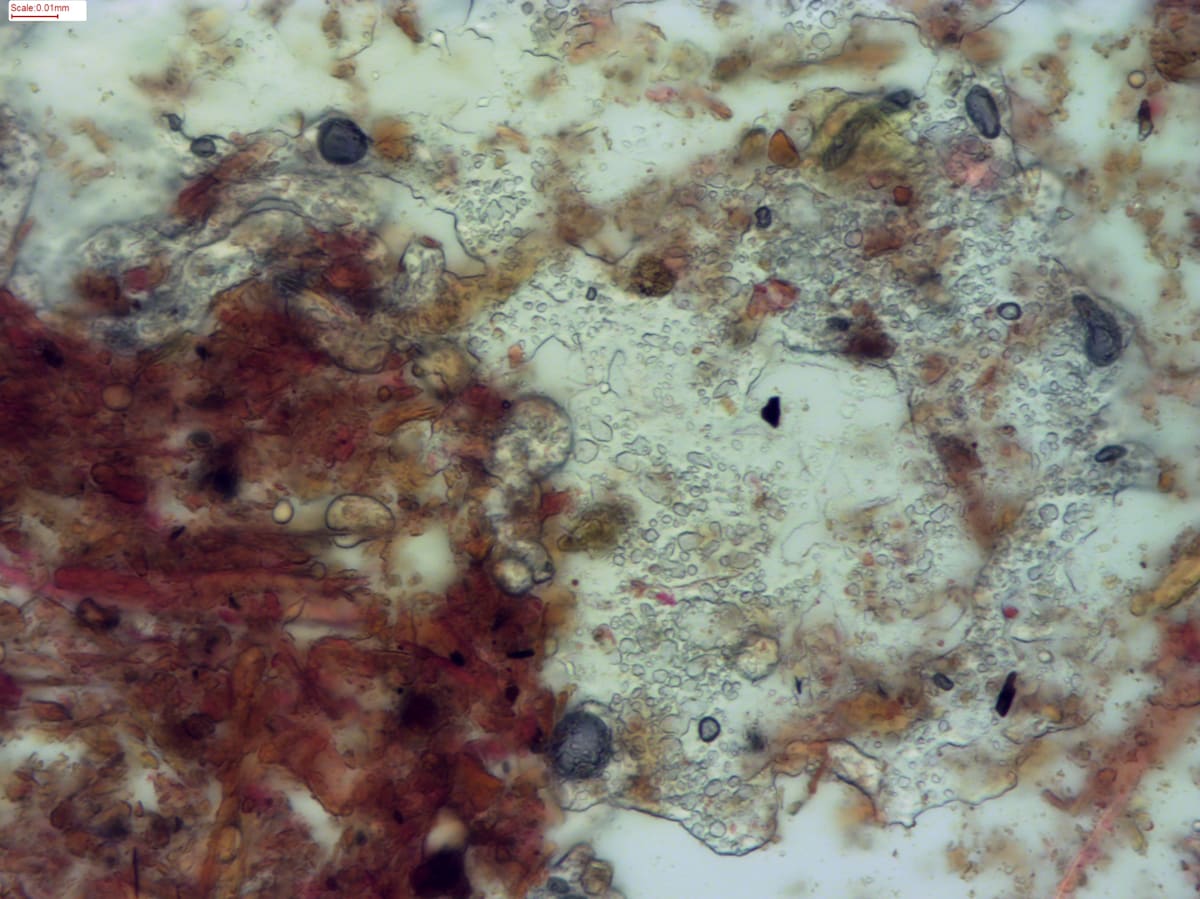

Researchers found buried 11,000 and 12,000-year-old miniature fireplaces with protruding trimmed wooden artefacts or sticks made of Casuarina wood, smeared with animal or human fat. They had been burned at very low temperatures, each for a short time. No food remains were associated with the fireplaces, “matching the configuration and contents of GunaiKurnai ritual installations described in 19th-century ethnography”.

Those wonderfully preserved buried miniature fireplaces with their prepared protruding sticks revealed by the archaeology date back to the end of the last Ice Age.

They are Australia’s oldest known wooden artefacts. They also signal some 500 generations of cultural transmission of a very particular ritual performance.

The researchers say no other ritual in the world has the tell-tale archaeological remains traceable so far back in time as these sticks.

The researchers write that the way the single sticks were prepared means the fireplaces were not for cooking or heating, and they cite 19th-century ethnography, in particular Alfred Howitt, an English geologist and pioneer ethnographer who migrated to Victoria in 1852.

He recorded vast amounts of information about GunaiKurnai culture from GunaiKurnai Elders and other community members through the latter half of the 19th century, including details of cave use and rituals.

Howitt described ritual fires and smearing fat or fluids on “magic” throwing sticks imbued with great spiritual power. These wooden implements were called “murrawan”, and their makers and users “bungil murrawun”.

Each of the GunaiKurnai clan groups had their own cave, and each cave had a “doctor, called a Mulla-mullung”, says Uncle Russell Mullett, who could cure but also summon harm, so they were both feared and sought-after.

“It's very, very exciting,” he says of the new findings. “Extraordinary. It’s a time capsule that’s preserved things so well. Everything that’s come out of the small excavations has produced information that’s opened the door to a broader understanding of the cultural use of the place.”

Professor Bruno David, an anthropological archaeologist from the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, says the project unearthed “astonishing” finds.

“You don't find these kinds of things in archaeology because the wood has normally disintegrated. Not only that, these are really special fireplaces.

“People did not use them to make heat or to cook things. We know that because of the scientific findings that were made during the excavations, together with the cultural knowledge that the Elders have and that Howitt wrote about from GunaiKurnai knowledge-keepers of the time.”

The sticks and fireplaces are “hidden stories” that remained buried under the soil for thousands of years – “that's culturally meaningful not just for science, but more importantly for the community.

“This kind of research, it’s cultural research, so it'’ got to be based on trust, on understanding, and respect and mutual learning as well,” Uncle Russell Mullett explains. “The 1970s excavations gave nothing back to the community, whereas now, 50-odd years later, there is a kind of redress.

“The cultural lens of it is the important part. Yes, we can talk about science and write science papers, but it’s the actual culture, what was happening here and what was going on, that’s the big story.”