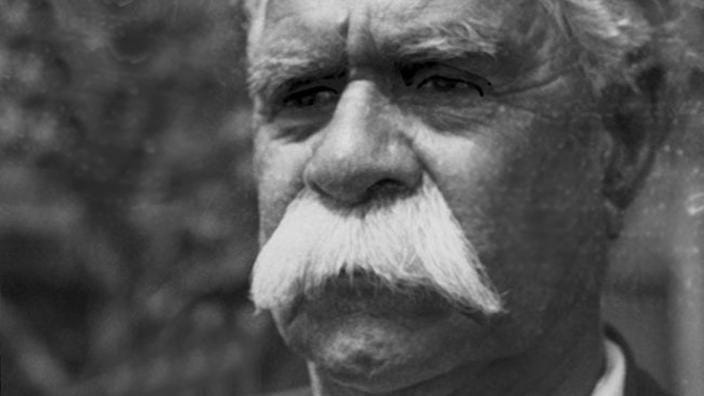

William Cooper was a Yorta Yorta man, born in 1861 in his own country, where the Murray and the Goulburn rivers meet. He lived between the worlds. His grandparents remembered the days before the white man came, and as a child Cooper witnessed a meeting of hundreds of Yorta Yorta men on their own lands.

Today, Cooper is best known as a visionary campaigner for his own people – for their equality under the law, and to be recognised as the land’s original custodians. In 1933, when he was 72, he founded the Australian Aborigines’ League. Four years later he sent a petition to King George VI arguing for an Aboriginal representative in the federal parliament, to be chosen by Aboriginal people.

“The league was one of the first organisations that was founded in order to fight for rights for Aborigines,” says Monash historian Professor Bain Attwood, “and in my view it is the most important.

“It had the greatest longevity, and also the greatest reach. Cooper was not only speaking for his own particular people, but trying to speak for Aboriginal people generally in Australia.”

Read more: What does it mean to be Australian?

The league was established in Melbourne after Cooper and his wife Sarah Nelson left Cumeroogunga Station on the Murray. Cooper applied for the old-age pension, and the couple settled in Melbourne’s inner west. They rented workers’ cottages without heating or electricity, and Cooper sometimes walked from Footscray to the city to save his train fare. But his modest independent income gave Cooper one great advantage – it allowed him to escape the oppressive authority of the government Board for the Protection of Aborigines.

“Under the protection legislation, you couldn't determine your own residence, who you married, the custody of your children, your labour arrangements,” Professor Attwood explains. By freeing himself of these restraints, Cooper was able to spend his last seven years as a champion for Aboriginal rights.

An Aboriginal representative was needed in the parliament, Cooper believed, because white lawmakers had shown themselves unable to understand the Aboriginal perspective' they could not “think black”.

Professor Attwood says Cooper’s petition “has a particular resonance now, as the reasons that he was seeking this are so similar” to the case for constitutional recognition and an Aboriginal voice in Parliament made in the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart.

In petitioning for an Aboriginal representative in the federal parliament, Cooper was also aware that the Maori had secured four seats in the New Zealand parliament, and that their sovereign rights had been recognised in a treaty.

In August 1937, Cooper’s petition was sent to the governor-general for despatch to the King via prime minister Joseph Lyons. The petition asked the King “to prevent the extinction of the Aboriginal race and better conditions for all and grant us the power to propose a member of parliament in the person of our own Blood …”.

More than 1800 Aborigines from every Australian state and territory signed the petition, despite government obstruction and fear of punishment. The document said the King had not only a moral duty but a “strict injunction issued to the commission to those who came to people Australia that the original occupants and we their heirs should be adequately cared for”. Instead, their land had been appropriated and their legal status denied.

Read more: Monash University’s Jacinta Elston: William Cooper an inspiration

Lyons’ secretary, rather than the prime minister himself, acknowledged its receipt more than a month after it was sent. The Commonwealth’s jurisdiction over Aboriginal affairs was limited, the letter said, but it was working with the states to do all it could.

Cooper was furious. In December 1937, he wrote a letter to Sir John Harris, the secretary of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society, which was also sent to The Times in London. The letter read, in part: “Our friends among the white Australians and our own educated Aborigines all agree that the prevalent attitude among those who at all take an interest in us is that the blackfellow is a ‘low, almost subhuman creature and the sooner he dies out the better’.”

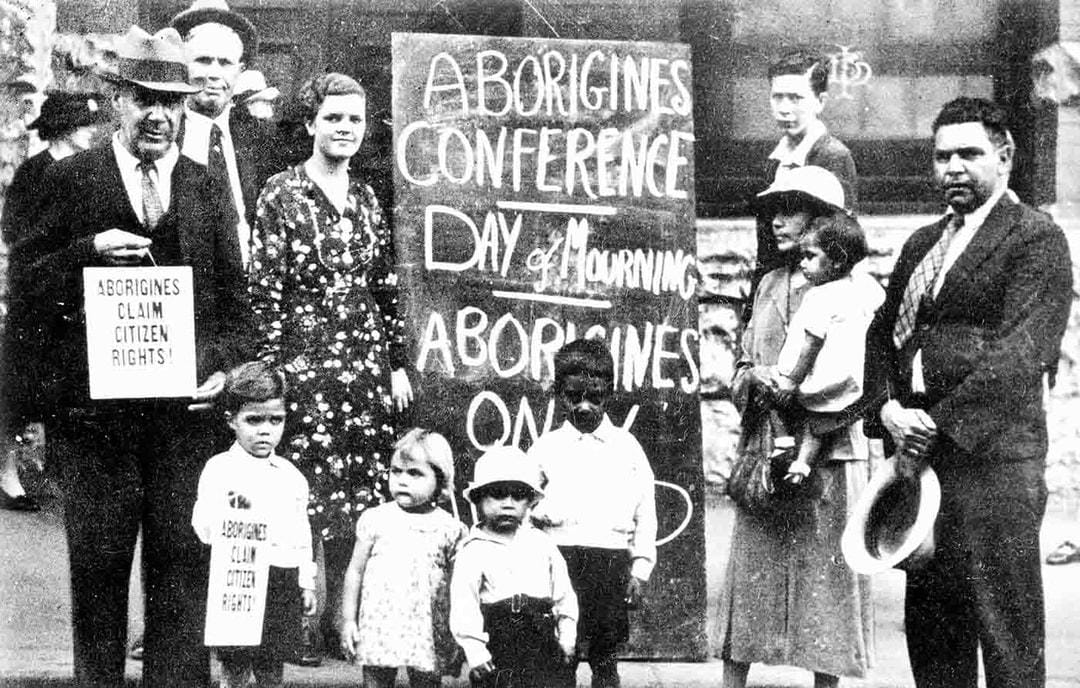

The league also generated headlines when it called for a National Day of Mourning to be held on 26 January, 1938, to coincide with the 150th anniversary celebrations marking the landing of the First Fleet.

The protesters asked for full citizens’ rights, and better education and healthcare for Aboriginal people. In a report in The Argus, Doug Nicholls, the Fitzroy footballer and Cooper protege, explained that Aborigines wanted more than to merely subsist on weekly rations. “We do not want chicken food,” he said. “We are not chickens, we are eagles.”

Cooper’s advocacy was all the more remarkable because he was self-educated, with limited formal schooling. Yet he thought strategically and analytically about how the Aboriginal cause could be advanced.

“An Australian anthropologist, Jeremy Beckett, once pointed out that Indigenous people not only have to endure colonisation, they have to understand it,” Professor Attwood says. “They're true intellectuals. Cooper is very much one of those figures.”

Read more: The William Cooper Indigenous Scholarship

Cooper was literate, but his letter-writing skills improved when he received help from two friends – Shadrach James, a European-educated Tamil who married Cooper’s sister, Ada, and who became secretary of the league, and Arthur Burdeu, a trade unionist and railway official who joined forces with Cooper in 1936.

“Burdeu and Cooper formed a meeting of minds,” says Professor Attwood. “Burdeu, quite unusually for a white man at the time, was a good listener, and I think he does faithfully represent what Cooper wanted in the letters he wrote on behalf of the league.”

This year, a First People’s Assembly was elected in Victoria to negotiate a framework for an Indigenous treaty – the first of its kind in Australia. Cooper esteemed John Batman for a treaty he signed in 1835 with the Aborigines who lived on the Yarra because it recognised the Indigenous peoples as owners of the land. (Batman’s treaty was immediately repudiated by Australian and British authorities.)

Yet five years later, in 1840, “the Treaty of Waitangi was made by agents of the British Crown in New Zealand, at the direction of the British government”, Professor Attwood says.

Australia is the only Commonwealth country without a treaty with its Indigenous people. An important factor was that Australia began as a government-run penal settlement, whereas in New Zealand, independent settlers negotiated what in effect were private treaties for land with the Maori before a government was established there.

Australia’s lack of a treaty “influences Cooper and many Aboriginal people, because it means that colonisation occurred here without their consent”, Professor Attwood says.

“That story becomes very important, and not just to Aboriginal people. There’s a kind of illegitimacy to our presence here, which makes treaty-making vital, for everyone. For all of us.”

Monash University has launched the William Cooper Institute, a platform for Indigenous advocacy and change. It aims to deliver improved opportunities and outcomes for Indigenous people and communities.