Australia has edged up four places in the climate change performance index, released during COP27, from 59 to 55 out of 63 nations. On policy, it climbed from 59 to 39, largely due to climate change legislation passed in September that mandated a new 43% emissions reduction target by 2030.

A big part of getting to this target is a parallel aim of 82% of electricity generation from renewables by the end of the decade.

As Australia’s Minister for Industry, Energy and Emissions Reduction, Chris Bowen, said in his COP statement in week two:

“The Future of energy is renewable [and] Australia wants to be a real energy superpower.”

The emissions target at least sets a new baseline for Australia’s responsibilities, which need to aim for more than 60% below 2005 levels if we’re to do our part in avoiding 1.5°C.

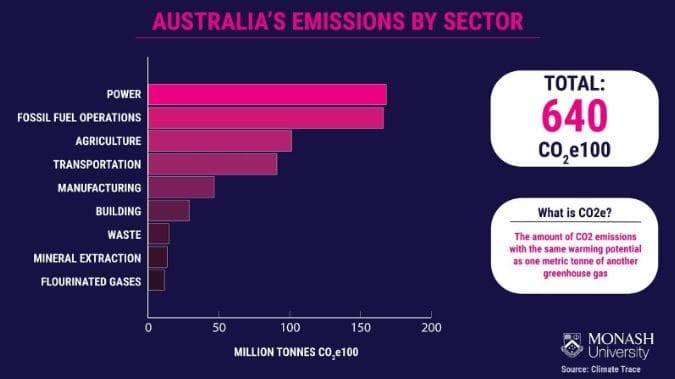

It’s worth noting that, according to the 2022 Global Carbon Budget report, Australia’s emissions have actually been in decline since 2005. However, this decline has overwhelmingly been achieved by reforms in land use and a dramatic injection of renewables into the energy sector, which has primarily been achieved by state government programs.

Most other sectors, such as transport, industry and agriculture, have continued to rise, and in fact, without the drawing down of emissions tied to land use, net emissions have been increasing overall.

At COP27, Australia added its support to a range of emissions reduction initiatives, including:

In the second week of COP27, Australia announced it had also joined the Global Offshore Wind Alliance (GOWA). Organised by the International Renewable Energy Agency, the GOWA aims to see 380 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind infrastructure built around the world by 2030.

In an interview with the Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub MCCCRH), Minister Bowen, on the penultimate day of COP27, said Australia was seriously lagging behind in offshore wind:

“Australia should be a leader, should be the leader in offshore wind. We're the world's largest island. We've got thousands of kilometres of coastline – we've got much more advantage of offshore wind than some of the countries that actually have done it. We have done no offshore wind in Australia – not one wind turbine offshore operates in Australia. This is craziness.”

But he said the new Labor government was “absolutely committed” to developing a strong offshore wind industry.

“It'll deliver a big part of Australia's renewable energy ... one offshore wind farm under development in Victoria will provide 20% of Victoria's energy needs. That's one wind farm. That's just the beginning, that's just the tip of the iceberg. I've joined the Global Offshore Wind Alliance because we need to learn from other countries who are so far ahead of us in what we've done. A lot of catching up to do – the alliance will help us do that."

There was also the announcement in week one that Australia was bidding to co-host COP31 in 2026 with the Pacific Island nations.

This latter initiative is an attempt to appease the Pacific, which has been frustrated and angry at Australia for being a laggard on climate for more than a decade.

In the first week of COP27, several Pacific leaders spoke at the Australia Pavilion:

- John M. Silk – The Marshall Islands’ former foreign affairs minister spoke of the prospect of losing the Marshall Islands in 25 years to sea-level rise.

- Umi Sengebau – The Palau Minister of the Environment: “Today we are being colonised by the impacts of climate change. The big polluters are the new colonisers. They need to step up and change their ways to ensure the more vulnerable nations have a chance.”

- Henry Puna – The Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum, and former Cook Islands prime minister, compared the vulnerability of the Pacific with Australian bushfires (Black Summer) and the ongoing flooding in NSW. “Climate change is not a Pacific challenge. It affects everyone now.”

Despite these voices being given the stage at the Australia Pavilion, Australia continues to join the US in deflecting calls to pay loss and damages to the least-developed nations, with the exception of the Pacific.

Earlier in the conference, Fiji’s Ambassador to the UN, Dr Satyendra Prasad, spoke at the Australian Pavilion, expressing that the Pacific was the only region to see a decrease in climate finance during the past decade.

Minister Bowen conveyed to the Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub that aid to the Pacific increased by $900 million in the budget, and that a new Pacific climate finance facility had been established, but that frameworks of loss and damage were still a “conversation” Australia was up for.

Nevertheless, a few days earlier, Bowen had taken to the stage to shift blame to the World Bank for not dealing with damage and loss at a global level.

Then there’s Australia’s sluggish approach to phasing out fossil fuels, in deference to big coal and gas, which a federal election hasn’t seemed to have influenced. Plans to rapidly transition to renewables haven’t been matched by decarbonisation of the resources sector.

It’s clear that the very idea of a “resources sector” needs to change if Australia is to wean itself off ancient fuels, which are permitted to pollute our atmosphere without the polluters paying a price.

On this point, Bowen emphasised the benefits of renewables in his interview with MCCCRH.

“Renewable energy is the cheapest form of energy – the sun doesn't send a bill, the wind doesn't send a bill, and we need more renewable energy in our system. We need 82% by 2030. That'll reduce power bills, because it's the cheapest form of energy. But also, we need to then move beyond that, because Australia can be the energy factory of Asia. We have more sunlight hitting our landmass than any other country in the world, we have above-average wind; we've got to harness that. We can export it, we can export it through cables – we're doing that. The Sun Cable project is a great project that’s made progress this week.”

According to Bowen, the Albanese government will be working hard on renewables.

Six months into office, it’s just getting started on safeguards policy, including ensuring Australia’s biggest emitters are reducing their emissions, developing a national electric vehicle strategy, and $20 billion to rewire Australia, which is needed to facilitate the energy transition.

How far these reforms will go in Australia meeting its international commitments is yet to be determined.

At current emissions levels, the world stands on the precipice of getting to 1.5°C in just under seven years. While Australia is keen to host COP31, in 2026 we’ll already be more than halfway towards a dangerous climate that cannot be reversed in an electoral cycle, or in any time scale that politicians care about.