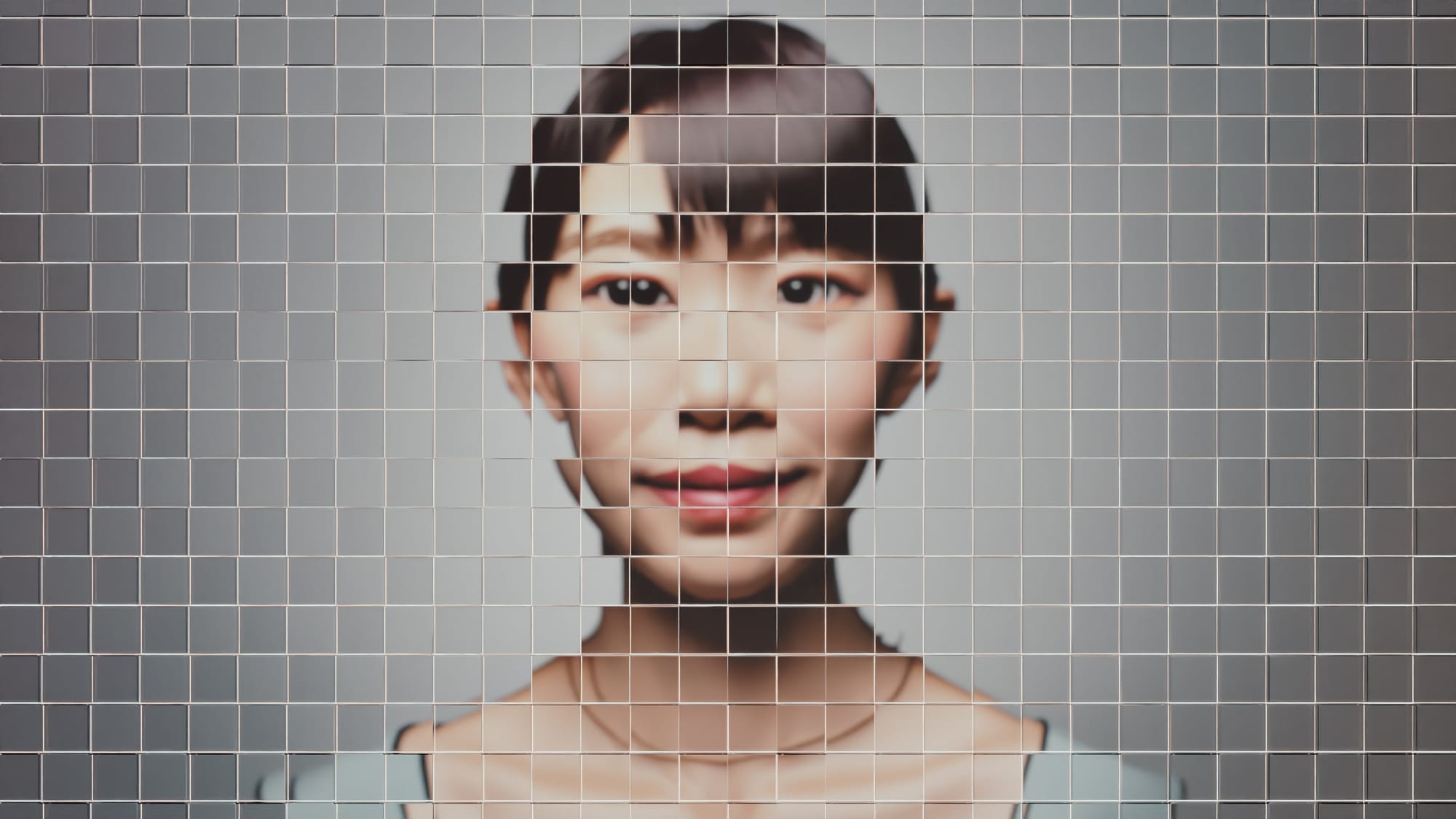

Deepfake technology is reshaping the boundaries of consent, privacy and safety. In September 2025, the Federal Court ordered a man to pay a A$343,500 penalty plus costs for posting deepfake images of several high-profile Australian women – the first major case under Australia’s Online Safety Act.

It was a landmark moment for AI-facilitated image-based abuse enforcement. But in South Korea, the scale of the crisis is far greater.

A global analysis by US cybersecurity firm Security Hero found that more than half of all deepfake pornographic videos online feature South Korean women, from pop idols and actors to students and minors.

In South Korea, the numbers tell a disturbing story. Data from the Women’s Human Rights Institute of Korea shows that 8983 people sought help for digital sexual violence in 2023 – a 12.6% increase from the previous year. Nearly three-quarters were women under 30, and reports involving deepfake images more than doubled over the past year.

The centre handled about 250,000 requests for assistance, most of them pleas for image deletion, revealing not only the scale of abuse but also the growing urgency of digital safety.

Vulnerable digitised society

These numbers reveal a paradox. South Korea leads the world in fighting digital sexual violence, yet its highly digitalised society remains uniquely vulnerable to new forms of abuse such as deepfakes.

South Korea is often recognised as a leading adopter of digital innovation. In one of the world’s most wired societies, the same technology that connects people also creates new risks, making women especially vulnerable to digital control and exploitation.

The 2019 “Nth Room” case, an encrypted chat network that orchestrated large-scale sexual extortion of minors, exposed how encrypted and anonymous digital infrastructures can both enable and conceal gendered violence, allowing coordinated abuse to thrive within the architecture of everyday technology.

The temporary shutdown of the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC) in mid-2024 exposed the cost of this institutional gap. For several months, more than 12,000 illegal sexual images, including deepfakes, awaited removal amid political gridlock.

Parliamentary data shows that the KCSC reviewed more than 15,800 deepfake images between January and July 2024, as cases surged from just 1900 in 2021 to more than 23,000 in 2024.

After this breakdown, Seoul City launched an AI-based system to detect and remove illegal sexual images around the clock.

The surveillance-protection balance

Yet as these digital safety measures expand, they also reveal a persistent tension between surveillance and protection, showing how Korea’s high-tech governance still struggles to ensure consistent and effective protection for those affected.

Yet deepfakes are not only used by strangers. Increasingly, they’re being weaponised within intimate and peer relationships, used for blackmail, control and coercion after breakups or conflicts.

Research on technology-facilitated abuse shows image-based abuse is often part of broader patterns of domestic and sexual coercion. Victim-survivors describe the constant fear of exposure – the threat that an ex-partner could recreate or circulate sexualised images at any moment – blurring the boundaries between digital and physical safety.

Earlier analyses have noted that without ethical and gender-aware governance, artificial intelligence risks amplifying inequality. A year later, the technology, and its misuse, have both grown more sophisticated, leaving open the question: Can progress and protection truly coexist?

This reform was built on an earlier legislative milestone – South Korea’s 2024 law criminalising not only the creation and distribution, but also the possession and viewing of deepfake pornography, with offenders facing up to three years in prison.

Read more: Digital child abuse: Deepfakes and the rising danger of AI-generated exploitation

In April 2025, the government launched the National Centre for Digital Sexual Crime Response, a 24/7 hub designed to coordinate reporting, counselling and deletion support across all 17 provinces. The centre integrates AI-based systems for the automatic removal of deepfake and illegally filmed content and expands undercover investigations into closed platforms such as Telegram.

The initiative forms part of Korea’s second Basic Plan for the Prevention of Violence Against Women (2025-2029), signalling a shift towards a more unified and proactive national response to digital sexual violence.

These reforms came alongside Korea’s new AI Basic Act, which aims to promote safe innovation. But critics say the law overlooks gendered harms such as deepfake abuse, showing why AI governance must protect those most at risk.

Limited international collaboration

Despite this progress, international collaboration on AI-related gender-based violence remains limited. Deepfake abuse manifests differently across countries, from intimate-partner coercion and blackmail to large-scale exploitation of women’s images.

Yet most responses remain siloed, shaped by national legal frameworks and cultural attitudes towards privacy, sexuality and consent.

Our Monash Australia-Korea collaboration project, Responding to Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence: AI and Digital Safety, examines how artificial intelligence intersects with gender-based violence across three dimensions: AI as a tool for detection and monitoring, a governance object shaped by regulatory efforts including the AI Basic Act and platform governance frameworks, and a source of new forms of harm, particularly AI-generated image-based abuse that enables coercive control, collective sexual harassment, and technologically-amplified social punishment.

Together, these perspectives explore how AI can both protect and endanger, and what ethical and policy responses are needed to ensure it serves those most at risk.

Digital safety, gender equality inseparable

South Korea’s recent reforms mark a turning point in the global conversation on AI and gender-based violence. While no system is flawless, the country’s dual response, combining advanced technology with stronger victim-survivors protections, reflects a growing recognition that digital safety is inseparable from gender equality.

As governments worldwide rush to embrace AI innovation, South Korea’s experience offers an important reminder – progress must be measured not only by speed or efficiency, but by whose safety it safeguards.

The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence initiative (25 November to 10 December) is a timely reminder that technology can both empower and endanger. Deepfake abuse reveals how power and inequality are being reprogrammed through new digital tools, and why accountability must be built into every layer of innovation.

Real safety in the age of AI will require more than laws and algorithms – it demands an ethical commitment to design technology, not harm.