Today, 8 June, is World Oceans Day. Why is that important?

Because “Earth” is a misnomer – we’re actually a water planet. More than 70% of it is covered in ocean. The ocean brought our original life about four billion years ago, which is incredible in itself, as we may be the only life in our 400-billion-star galaxy.

And the oceans continue to support virtually all life on the planet even today. The health and structure of the oceans plays a direct and indirect influence on all of our lives.

As climate scientists, we might quibble a little with the World Oceans Day’s slogan of “One ocean, one climate, one future – together”, as we actually have multiple plausible oceans, climates and futures. All depend on how much carbon dioxide we choose to emit in the future, and we’re in this together.

Also, you might think if you live in the interior, away from the coast, such as in Coober Pedy, Alice Springs, Mildura or Mount Dandenong, then surely the ocean has no effect on your life? In fact, the oceans affect us all, directly and indirectly, through multiple facets of our lives, and often without us even realising it.

Of course, if you live on the coast it can be obvious even on a daily basis. If you’re a surfer, like we both are, it’s in everything from the temperature of the water dictating your choice of wetsuit, to the size, direction and the period of time between the waves you surf, to the shifting sandbars that dictate the best spot to surf.

It may not be as obvious that the ocean (or rather, the difference in ocean temperature and land temperature) is also causing the sea breeze that ends your session, but it does.

If you’re living 1000 kilometres inland, the impact on your life may be hard to see, but it’s definitely there. The climate you experience every day is, in Australia, largely driven by the oceans that surround us. That means even in the back of Bourke, your weather is generally a product of the oceans.

For instance, while plenty of people know of El Niño as the thing that brings drought, and conversely La Niña bringing wet/flood, the El Niño and La Niña weather patterns are driven by changes in tropical Pacific Ocean temperatures.

During El Niño, the ocean is warmer than usual near South America, so that's where the air tends to rise and clouds and rain form. But you don’t get something for nothing, so the air that goes up then goes down again over on our side of the Pacific, giving us in Australia big, clear rainless high-pressure systems and drought. The reverse happens with La Niñas and floods.

Warm oceans nearer to Australia also have a double-whammy effect by helping warm the air and raising the humidity. Hence, when you have storms and weather systems that cause rain, both near the coast and inland, they pick up more moisture over a warm ocean than a colder one on the pathway to your location.

This is where climate change comes in. Our oceans will increasingly play a far more noticeable role in our lives. And the first half of 2025 clearly demonstrated that, with natural disasters costing Australia $2.2 billion, according to Treasury.

The global ocean actually absorbs about 90% of the excess heat produced as a result of increasing greenhouse gases. And how much heat is that? About five to six Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs of energy being stored in the sea every second of every day of every year.

This also means that the ocean will ultimately transfer the heat we generate now to the generations of the future.

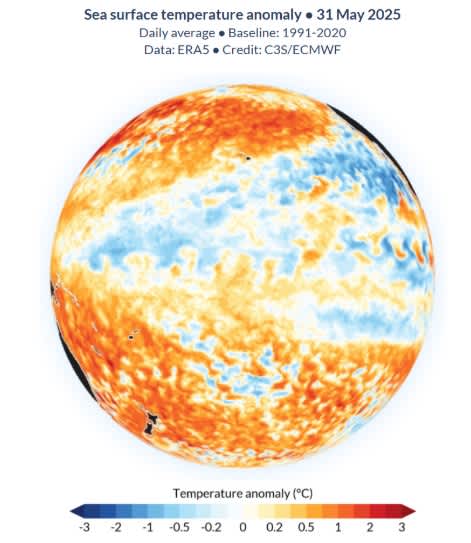

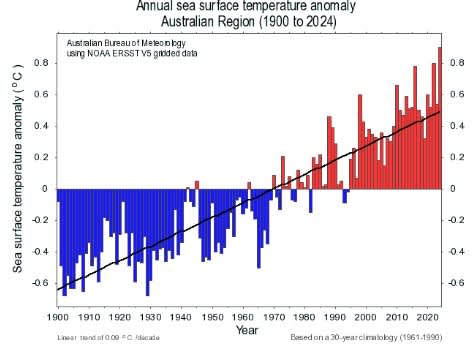

While 2025 has seen neither El Niño nor La Niña, January and February recorded the hottest sea surface temperatures on record around Australia, while every month since has ranked as the second warmest. Those records go back to 1900 – 126 years.

Globally, 2024 was the hottest year on record for the world's ocean, and not just at the surface, but all the way to at least 200 metres deep, while as of early June, the daily ocean temperatures are sitting third-warmest.

All this warm ocean water played a huge role in making 2024 the globe’s hottest year on record. But as every degree of warming means an extra 7% of moisture in the atmosphere (and we are sitting around 1.5°C warmer than normal), it also means every rain event now packs just that bit more punch.

We like what Jas Chambers, the chair and co-founder of Ocean Decade Australia – a not-for-profit organisation interested in ocean governance – has to say. She stresses change is possible, and we have the science and the evidence.

She writes that action is:

“... making decisions about ocean areas that require restoration, conservation, and protection. It includes the development of policy and regulations – be that for the infrastructure we build or the design of alternatives for energy, food and transport available. It also includes individual choices and being personally proactive…the time to act is always as soon as possible, because every fraction of a degree matters."

Which brings us back to 2025 in Australia.

This year, we’ve directly experienced impacts from the oceans in the form of several marine heatwaves. The most notable started in September 2024 and continues now, stretching down the West Australian coastline – arguably the most severe marine heatwave ever seen off the west coast.

Its most prominent impact was the worst coral bleaching on record for Ningaloo reef, and the first ever mass bleaching across the inshore Kimberley and at the Rowley Shoals.

Down the east coast, the marine heatwave brought the second year in a row of coral bleaching over the Great Barrier Reef. A double-year event also occurred in 2016-17.

The 2025 bleaching event was the eighth mass bleaching of the reef, and sixth since 2016. Prior to 1998, there was no record of coral bleaching events, even in the stories of Aboriginal people stretching back thousands of years.

A marine heatwave also appears to be a significant contributor to massive algal blooms off South Australia that led to fish kills and even sickness for people who went into the water. Sadly, algal blooms are expected to become more common as the ocean warms and more flood events provide nutrients to feed the blooms.

Further south, some have questioned the role of marine heatwaves in recent salmon deaths off Tasmania, as warmer waters promote certain parasites and viruses that attack the fish.

Read more: Devastatingly low Antarctic sea ice may be the ‘new abnormal’, study warns

Climate change does not just warm the ocean, but that warming causes the ocean to expand. As the water cannot expand sideways (much) or down, the only way is up, raising sea levels globally. Plus, the ocean is getting more water from glaciers and melting ice caps.

Sea levels have increased by about 22cm since pre-industrial times, and their rise is not only accelerating, but will continue for millennia even if we stop emitting greenhouse gases today. By the end of the century, one or even two metres of sea-level rise is entirely plausible.

This means that every big storm can potentially generate more coastal erosion and more coastal and estuarine flooding than it did in the past.

So far in 2025 there has been coastal flooding and erosion associated with Tropical Cyclone Alfred along more than 500km of Queensland and NSW coastline, while in late May a storm eroded and flooded the coastline of southeast South Australia. In both cases, raised sea levels compounded the impacts of a storm surge and very high tides.

And finally, there are the indirect impacts of our changing oceans.

Remember that relationship between warmer oceans, warmer air and more moisture in the atmosphere? In May, vast swathes of eastern Australia experienced record rains and flooding, and rapid attribution studies have already suggested some link to climate change.

While the degree of attribution will be debated in science for some time, clearly warmer-than-normal air passing over warmer than normal oceans will have resulted in extra moisture available for rain to fall in the right meteorological conditions.

In many ways, we now need to reframe how we think of flooding, as it would appear near-impossible to detangle impacts from our human enhanced hydrological cycle.

Sadly for life on this planet, the oceans will continue to get warmer, higher and more acidic, even if additional human emissions stop today.

Impacts will include infrastructure damage, particularly along our coastlines, social and cultural upheaval (for instance, Torres Strait Islands flooding, and community displacement), environmental damage to reefs, plants and animals (changes in acidity will further slow reef recovery and impact anything with shells), and even hit our hip pocket via raised local rates and taxes for disaster recovery, increased building costs, and, as we’re already seeing, higher insurance premiums.

This is just a small fraction of the systems that are, and will, experience impacts as the ocean changes.