The global conversation on global warming rarely includes the voices of women in remote villages in Africa, Asia or on Pacific islands – even when they're on the front line of climate change.

These women have to feed their families when their fields flood, their livestock perish, or when a cyclone hits. They may have little schooling; their knowledge might come from their mother, or grandmothers.

To survive today, they're forming networks to support and learn from each other – and international bodies are now recognising their importance, and want to help.

Gender Responsive Alternatives to Climate Change, a report by Monash University’s Gender, Peace and Security Centre and ActionAid, examines local women’s networks in Cambodia, Vanuatu and Kenya. The consequences of global warming are already evident – in different ways – in these three countries.

“The point of this research is engaging with women at the community level who have very little resources and very little voice, but are very aware of the problems,” says co-author Professor Jacqui True.

In rural Kenya, for instance, incidents of female genital mutilation rise in drought years, as families marry off their daughters at a younger age – they're traded for cattle, and the procedure is believed to render them more marriageable.

Cattle-rustling rises, too – young men need cattle to marry, which gives them status. Among the Pokot people, decisions about where to relocate are also made by men. The men don't take access to water and firewood into account when choosing new territory – these are women’s responsibilities, and women aren't consulted.

The Tangulbei Women’s Network (TAWN) allows Kenyan women affected by this scenario to meet, talk and share information. “We support each other,” says a TAWN member quoted in the report. “We want a collective voice, because then we have more power. Becoming part of a network is protection.”

The report argues that women in grassroots organisations such as TAWN would be helped further if they also had access to a “big-picture” education about the causes of global warming and how their governments are responding. It recommends that women be trained to train other local women, so that knowledge is spread.

“Global warming is part of the material lives of these women, and it's also part of their commitment,” says Professor True. “They've developed strategies and responses to it, but they're the last ones to be consulted.”

The report says not only the women need to be educated. Decision-makers must also be more willing to listen to these women, and to learn from their experiences.

“We need to create forums where there's an exchange and an understanding rather than a hierarchy. Because right now, I don't think Western science is winning the debate, right?”

That proposal is not news to the women in the report. “Knowledge about climate change is new, even to local authorities,” says a Cambodian woman. “They don’t understand, but if you talk about natural disasters they understand. So we start with why disasters are happening more frequently, about rain patterns … We start with their local knowledge first.”

In Cambodia, men leave the villages to work in garment factories for cash, forcing the women to farmland that is increasingly prone to flood. (A similar pattern is seen in Bangladesh.) “We learnt how to farm from our mothers … What to plant depending on the availability of water, how to tie rice stalks, and harvesting,” one woman told the report. Traditionally in Cambodia, harvesting was a communal practice.

The report says policymakers also need to be open-minded about different kinds of knowledge – traditional and indigenous as well as scientific and technical. Indigenous people can hold precious stores of information that has been collected and passed down over generations.

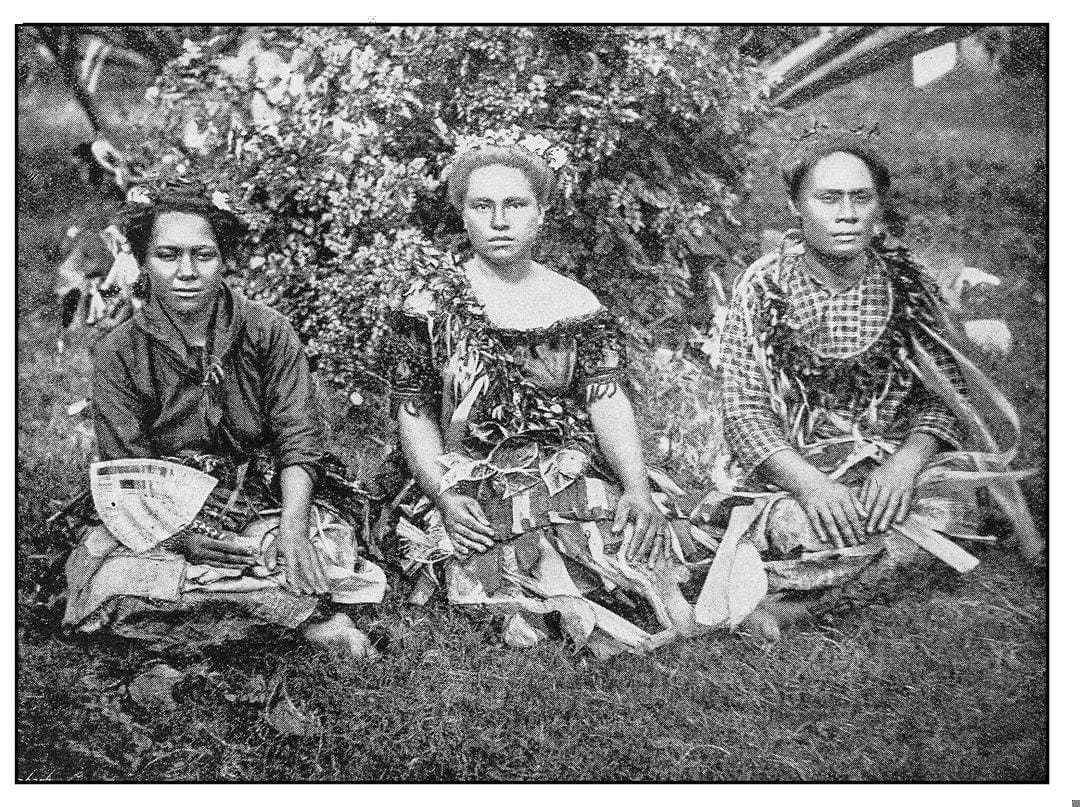

After Tropical Cyclone Pam struck Vanuatu in 2015, for example, the indigenous Tanna women had no access to disaster relief. But they were able to identify food sources, and also knew how to prepare the food – this helped their people survive. Tanna women also helped monitor their community’s welfare before and after the cyclone, relying on networks established in the largely female village produce markets.

The report recommends promoting women as gatherers of local information about the risks of climate change and connected crises in their community. This will allow them to present – and establish – their knowledge to authorities.

It also recommends that the barriers preventing women from taking a more active role be dismantled – these barriers include cultural norms, gender-based violence, and access to resources (such as fares and childminding). Practical support would allow them to participate in forums – where women are under-represented – and to take a place beside male decision-makers.

"They have devised some solutions, in spite of very meagre resources, education, access. It does give you tremendous optimism about human innovation.”

“We need to bring different types of knowledge together,” Professor True says. “We need to create forums where there's an exchange and an understanding rather than a hierarchy. Because right now, I don't think Western science is winning the debate, right?”

She points out that around the world, a predominantly technical response to climate challenge has proved inadequate “because a lot of people are not moved by reason or rationality. They're moved by faith, by emotional appeals, by leadership, by what they need to do to look after their material needs.”

Professor True argues that these “so-called non-scientific approaches” can be used positively “to bring people on board with sustainable practices so that we can preserve, conserve our planet for future generations”.

“When you do research like this, you meet people on the ground who can connect all these issues themselves, they can think holistically,” she says. “And they have devised some solutions, in spite of very meagre resources, education, access. It does give you tremendous optimism about human innovation.”

Women's role recognised

The research was funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which has been open to its findings, she says. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change also recognises that women need to play an equal part in the fight to limit global warming.

Read more Fighting climate change with translation, language and stories

Women need to be encouraged to take their place at the decision-making table, because experience already shows that when women’s voices are heard, change is more likely to happen, Professor True says. Countries with the greatest proportion of women in their parliaments are the most active in mitigating global warming.

She points out that in the West, leadership in the climate debate is also emerging in “non-traditional” places. She cites independent climate campaigner Zali Steggall, who defeated climate change sceptic and former prime minister Tony Abbott in the last election, and Helen Haines, the second-generation Indi independent, who called for a national agriculture and climate change strategy when she entered Parliament. Such women tend to be issues-oriented rather than career politicians.

But the outstanding example of unexpected leadership has come from Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg, who's persuaded schoolchildren around the world that they also have a voice and should take a stand for the planet, too.