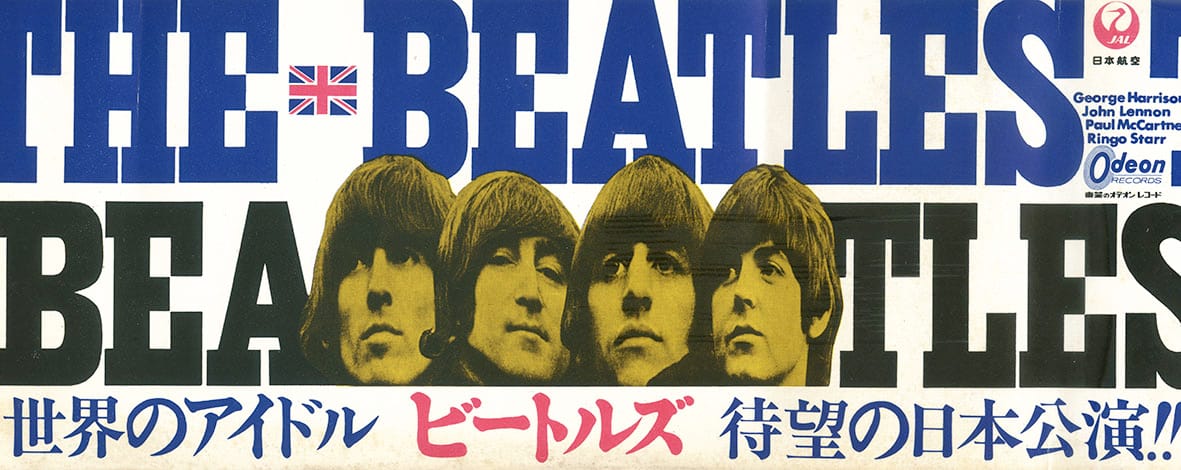

When the Beatles arrived in Japan on June 29, 1966, they were the biggest rock band the world had seen. The Liverpool lads walked off the Japan Airlines jet, hands raised to the sea of fans they expected would be there to greet them, but found themselves instead surrounded by security personnel.

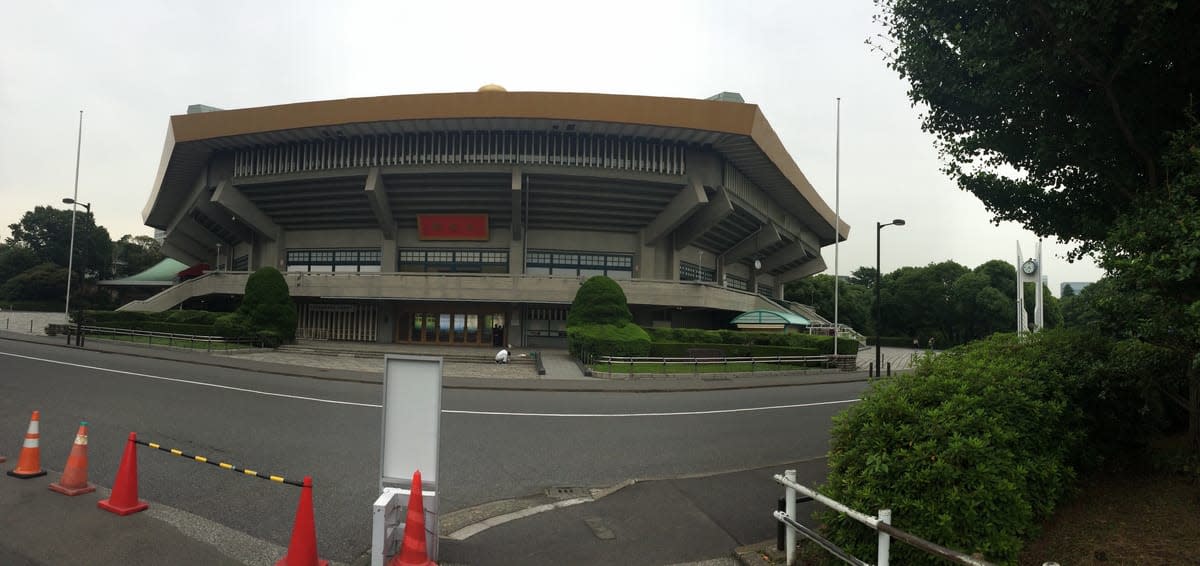

Throughout their brief tour, Japan kept defying the Beatles’ expectations. The band performed five shows at the Budōkan – a martial arts stadium built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics – and stayed in the presidential suite at Tokyo’s Capital Hotel. They received very few visitors and weren’t allowed to leave the premises, which puzzled them.

The teenagers who attended their concerts screamed, like teenagers elsewhere, but remained seated throughout, giving the Budōkan concerts an unusually restrained atmosphere.

“The boys were in a bubble,” says Monash's Professor Carolyn Stevens, who’s written the book The Beatles In Japan (Routledge, 2018). “They weren’t even allowed to go shopping.” Their Japanese hosts “brought in things for them to buy. John snuck out, and he got as far as an art gallery, then he got caught. Paul snuck out; he got almost to Meiji Shrine.” When John and Paul were found, they were politely escorted back to their hotel room.

“The only other confirmed visitors brought in to see them were a female journalist named Rumiko Hoshika from Music Life – it was one of the more popular monthly magazines at the time. She had met them before, when she’d travelled to England to see them. A male pop singer named Yūzō Kayama was brought in to have dinner with them, but he then left quickly after the meal.”

Death threats

What the Beatles didn’t know was that they had received death threats – they learned about them only after leaving the country. “Their management only found out about it after they had arrived, and they decided not to tell the boys, because they wanted them to have a good time and perform well,” Professor Stevens says.

The Tokyo authorities were particularly afraid of snipers. “That’s why they wouldn’t let the girls stand up” during the concerts; they wanted clear views from strategic points throughout the arena. Compounding these concerns were public protests – when the band travelled through Tokyo, “protesters from right-wing groups lined the streets, saying the Beatles were insects that needed to be crushed”.

At the same time, “there was a spontaneous expression of happiness and joy” when the Beatles arrived in Tokyo, Professor Stevens says. After the triumph of the 1964 summer Olympics, there was an eagerness to demonstrate to Westerners how Japan had successfully reconstructed its nation after its surrender in World War II. Tokyo authorities wanted to prove once again that Japan could handle the logistical challenges associated with a world-class event such as hosting the Beatles.

In parallel, “there were some students, underground groups and more prominent leaders, including journalists, politicians and leaders of industry, who were uncomfortable” with Japan’s rapid modernisation. These people, not part of a single, unified movement, weren’t necessarily against the Beatles themselves, but they didn’t approve of Western pop stars performing at the Budōkan.

“They said the Budōkan is a sacred place for martial arts. And it’s located very close to sacred spots – the Yasukuni Shrine and the Imperial Palace … they thought, do we really want a big rock concert there? The concert was an affront to their sense of tradition. They asked, why does Japan’s future have to be Western? Can Japan have a future that is Japanese?”

A longtime fan

Professor Stevens says she wanted to write the book because she’s been a Beatles fan since she was five years old in the US, playing her parents’ copy of Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. She’s also a Japan pop-music enthusiast, and worked as a translator and pronunciation coach in the industry in the early 1990s. Ten years ago she wrote the book Japanese Popular Music: culture, authenticity and power (which spanned from 1945 to 2008). A book on the Beatles in Japan seemed like a natural follow-up.

There’s also a personal connection. In 1993, while working in Tokyo, she received VIP tickets to see Paul McCartney. It was his first visit to the country after being expelled for possessing marijuana in 1980. “My seats were third row, centre. We made eye contact and we even spoke briefly. I was so thrilled that I was able to have a personal interaction with a Beatle after being a fan for so long.”

For her research, Professor Stevens sourced Japanese accounts of the tour and found two concert-goers to interview about their experiences. One, a woman now in her 80s, said she couldn’t hear anything “except for when Paul sang Yesterday, when everyone was quiet. But aside from that, they were screaming the whole time.”

In their own words

Professor Stevens also looked at what the Beatles and their entourage wrote about their Japan days. This included George Harrison’s autobiography, I, Me, Mine, and the eight-hour audio-visual memoir Anthology, made by Paul, George and Ringo in the mid-1990s. Tony Barrow, the press agent who decided not to tell the Beatles about the death threats, also wrote about the tour in his memoir, John, Paul, George, Ringo and Me: the real Beatles story.

Despite their seclusion in Tokyo – or perhaps because of it – the Beatles had fond memories of Japan, Professor Stevens says.

In the US, there were shots taken at their cars, and firecrackers thrown on the stage in Memphis; none of those incidents ever happened in Japan.

She argues this view was influenced by their subsequent misadventures in the Philippines, where their manager, Brian Epstein, mishandled an invitation for them to visit the Marcoses at Malacanang Palace. Their non-appearance was perceived as an unforgivable snub, and the tour ended with the band members being manhandled at the airport when they left. They were also forced to forfeit most of the earnings from their two Manila shows. “They had a terrible time,” Professor Stevens says.

In August of that year, the Beatles also went to America, where they faced more threats when the Bible Belt states reacted to John Lennon’s throwaway remark in England months before that “we’re more popular than Jesus now”.

“In the US, there were shots taken at their cars, and firecrackers thrown on the stage in Memphis; none of those incidents ever happened in Japan,” Professor Stevens says.

After the 1966 world tour, the Beatles never again performed live before a paying audience.