"[Gender] doesn't explain everything, it doesn't explain nothing, it explains some things. And it is for the nation to think in a sophisticated way about those shades of grey." – Julia Gillard, 2013

Amid the turmoil of the past week, the smile of Julie Bishop has beamed out from newsstands. Being published just before the commotion, the latest edition of the Australian Women’s Weekly profiles an assured and at-ease Julie Bishop. As always, she describes herself in several ways, but one label that she continues to resist is “feminist”.

Yet, before the Weekly’s presses even had time to cool, Julie Bishop has resigned her position as Australia’s foreign minister, her role as deputy leader of the Liberal Party, and with it her position as a senior cabinet member.

In a further blow, she received only 11 out of a possible 85 votes in the party room when, after 10 long years as deputy, the well-qualified and well-respected party stalwart finally made a run at the top job.

Since announcing her decision to move to the back bench, Bishop has received nothing but praise from colleagues and opponents alike.

Since announcing her decision to move to the backbench, Bishop has received nothing but praise from colleagues and opponents alike. In fact, throughout the debacle of the past week, she has rarely faced criticism from within or without the party.

On Sunday’s ABC Insiders program, the (now former) education minister Simon Birmingham described her as the most significant woman in the history of the Liberal Party, former prime minister Turnbull referred to her as the finest foreign minister Australia has seen, and her counterpart, Shadow Foreign Minister Penny Wong, demonstrated both respect and gratitude in her tribute to Bishop’s contribution to Australian political life.

And her popularity extends beyond her immediate colleagues. In fact, she is consistently the most popular Liberal politician in Australia. A Roy Morgan poll taken on Thursday found that she was, by far, the best-placed Liberal to beat Bill Shorten. On Friday a News Corp poll found she was overwhelmingly the preferred leader (despite her name appearing as last of six choices on the poll!) Bishop was undoubtedly a key electoral asset for the Liberal Party, a party that will undeniably struggle at the next election.

So why did she fail so spectacularly in her attempt to become Australia’s second female prime minister? Why was she, according to unnamed parliamentary insiders, unpopular within the party and seen by her colleagues to have no presence in the parliament? To quote Australia’s first female prime minister, gender doesn’t explain everything, but nor does it explain nothing. It explains some things.

Some might suggest that her gender is irrelevant. It has been said that it was time for the Liberal Party to have a new generation of leaders, and Julie Bishop was too close to Turnbull. Abbott’s former chief of staff Peta Credlin called Bishop “Turnbull in skirt”. Others suggested that she doesn’t have what it takes to deal with the conservative faction of the party and would face the same fate as Turnbull. Therefore, they argued, all strength needed to be put behind the boy from Cronulla.

But both arguments are problematic; each is heavily gender-biased. As deputy to four diverse Liberal Party leaders, Bishop deftly negotiated party room politics. Indeed, as Australia’s premier diplomat she managed multiple party room spills while appearing loyal, calm and well-considered.

We may not immediately recall her shouting across the floor of the parliament at her opponents, or promoting herself by publicly undermining her colleagues, but why is this our criteria for strong leadership? It should be quite the opposite, in fact. After all, nobody is suggesting that Bishop is behind the nasty politics of last week, that her actions were self-serving, or that she behaved with anything but integrity in her role as deputy leader.

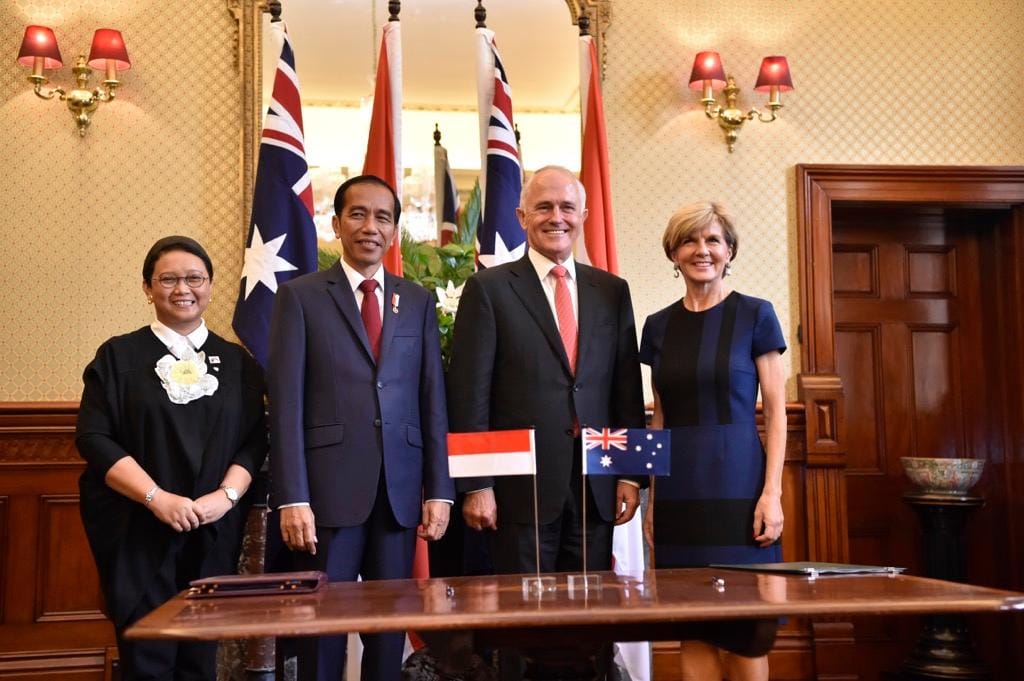

In fact, while we might find national pride in her professional handling of 'strongman' foreign leaders such as Vladamir Putin during the MH-17 investigations, or Joko Widodo during the execution in 2015 of two Australian citizens, we appear less ready to celebrate her quiet handling of the macho politics on display in the current government.

The combination of revenge-seeking, egocentric and opportunistic politics on display last week demonstrates that an aggressive masculinist politics continues to destabilise the leadership of the Liberal Party. And in the fury of this politics, the party room has simply overlooked Bishop as a legitimate and credible leader.

Ultimately, Julie Bishop is the collateral damage of the Liberal Party’s macho politics.

Ultimately, Julie Bishop is the collateral damage of the Liberal Party’s macho politics. Morrison has shown nous in moving Marise Payne into the portfolio, but Defence will feel her loss. And the loss of two strong, competent and well-respected leaders at the helm of two traditionally masculinist portfolios is a step backwards for the Liberal Party.

After all, this is a party that already struggles to gain credibility with those voters for whom gender equality should be a part of everyday life in this country.

Julia Gillard hoped that her experiences and the lessons learned from them might make things easier for the next female prime minister. The politics of the past week suggest those lessons are not yet learned.

Maybe it’s time for Julie Bishop to come out, and declare herself a feminist after all!

This article was originally published on BroadAgenda. Read the original article.