With 4 August looming as the earliest possible date for an election of the full House of Representatives and half the Senate, the founder of the now-defunct Palmer United Party and former MP, Clive Palmer, has flagged his intention to run again. The new incarnation of the Palmer tilt will be the “United Australia Party”, which was also the name of the predecessor to the modern Liberal party.

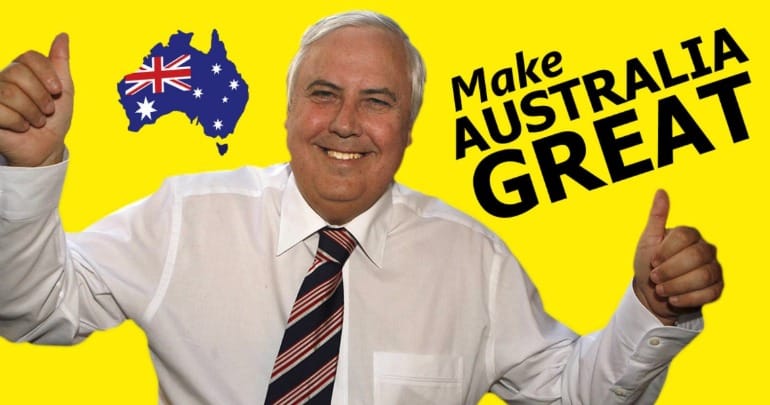

Presumably in a bid to hitch himself to Donald Trump-style populism in the United States, Palmer’s early election advertising signals his desire to "Make Australia Great".

Billboards featuring Palmer, his new party name and the slogan are popping up all over Australia.

Right-wing struggles

Palmer’s re-emergence seems somewhat ludicrous given the disasters that befell his former party following the 2013 election that saw him and three senators elected. For those who have forgotten, the PUP imploded almost the moment it tried to have the first meeting of its new parliamentary team, and Palmer was also pursued in the courts over his business interests.

The only survivor of the PUP era was Tasmanian Jacqui Lambie, and even she was unable to see out her next senatorial term, thanks to problems with her citizenship.

Given all this, it would seem Palmer’s return to the fray is another manifestation of his narcissistic nature, although there is also a strong hint of opportunism behind the formation of the UAP.

Read more: Mining magnate, property tycoon – politician? Just who is Clive Palmer?

In the past two general elections, an array of minor right-wing parties – be they anti-environment, socially conservative or populist – have captured seats in parliament, only to later disintegrate between election cycles. Presumably, Palmer sees a potential constituency and he is out to win its vote.

Palmer’s UAP is yet another in the pantheon of right–of-centre minor parties that have grown in number over the past three electoral cycles that have been notable for their volatility and lack of discipline.

The re-emergence of Pauline Hanson and the One Nation party is a case in point. Having struggled to survive after the 1998 election, One Nation re-appeared in time for the 2016 Senate vote, securing four seats and exercising some cross-bench influence over the balance of power in the upper chamber.

Read more: The mice that may yet roar: who are the minor right-wing parties?

However, from the moment the parliamentary team got together, One Nation started to fall apart through the disqualification of senators and ongoing tensions between Hanson and the remnants of her party.

Indeed, the implosion of One Nation since the 2016 election may well have been the catalyst for Palmer’s re-mobilisation, especially in Queensland, where the populist, anti-establishment vote has been quite strong for some time.

Palmer has been the beneficiary of this vote in the past. In 2013, Palmer won the lower house seat of Fairfax, and Glen Lazarus, who led the PUP Senate ticket in Queensland, easily secured a seat in the upper chamber.

The PUP lost the populist vote to One Nation in the 2016 election, but with One Nation’s recent struggles, Palmer clearly thinks he can win back this segment of the electorate and return to national politics.

Uncertain return

There are some serious obstacles ahead of him, though. First, it remains to be seen if his candidacy will be viewed as credible by voters, given what happened the last time he ran.

It’s also worth remembering the structural barriers that stand in the way of candidates from outside the major party system. Palmer’s party has flagged its intention to contest every lower house seat, but his candidates will be unlikely to garner 35 per cent of the vote anywhere – the minimum prerequisite for winning a seat.

The UAP’s best hope is in the Senate, and especially in Queensland. But here, changes to the Senate voting system will also hurt the party’s chances.

Unlike the 2013 election, Palmer and his party will be contending with a quasi-optional preferential voting system thanks to changes made by Malcolm Turnbull’s government two years ago. There is no guarantee all the primary votes cast for the plethora of tickets running for Senate in each state will flow through as preferences to other right-of-centre candidates.

Read more: Face the facts: populism is here to stay

“Preference-whispering” arrangements that were so important to the PUP’s success in 2013 will not be in place for the next Senate election. Indeed, the next election will be a half-Senate contest, which will make it even harder for minor-party candidates to succeed.

All of this serves to remind that, despite their larger-than-life personas, these minor-party populists like Palmer and Hanson win very small shares of the vote.

While he might try to plagiarise the American president, the truth is that Palmer is no Donald Trump. Trump was the official candidate of one of the two major parties that dominate the US political system and won nearly half of the popular vote in the 2016 election.

Palmer is a fringe player who will be depending on the interchange of preferences with other fringe players and the vagaries of the Senate voting system to be able to gain a foothold in the Australian parliament.

He will also need to hope the Australian electorate has either forgotten or forgiven him for his performance the last time he was in the parliament.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Nick Economou was a senior lecturer at Monash University at the time of writing this article.