Brands spend millions of dollars endorsing celebrities, including sports and movie stars, and when they get it right, it can be a powerful marketing tool – think Michael Jordan and Nike, George Clooney and Nespresso, or Beyonce and Pepsi.

But there’s always a danger that celebrity endorsements could backfire, too – think Tiger Woods and Lance Armstrong, who were both publicly disgraced for personal and drug scandals.

Celebrity endorsement also poses potential risks to advertisers when the celebrity unexpectedly undergoes an image overhaul (such as squeaky-clean Hannah Montana to Wrecking Ball Miley Cyrus), loses popularity (Gwyneth Paltrow’s ‘most hated celebrity’ status due to her controversial health advice), overshadows the endorsed brand (Angelina Jolie for St John), or engages in negative behaviour (Kristen Stewart’s affair).

Some scandals are beyond repair and the company cuts its ties, but for others a smile just might save celebrity appeal and consumer perceptions of celebrity genuineness, and thereby the campaign.

A smiling celebrity creates emotional contagion, which means it makes consumers automatically feel more pleasant after viewing the ad. However, smiling only works on celebrities when consumers are familiar with them and when the celebrity matches the product they’re endorsing (such as Matthew McConaughey with perfume versus a computer).

At least, the right kind of smile.

That’s right – there’s more than one way to smile.

Duchenne and non-Duchenne smiles

The American comedian Phyllis Diller once described a smile as “the curve that sets everything straight”, and new Monash University research is showing that this can be the case for marketers, too, if the celebrity endorser adopts what’s described as a genuine, or “Duchenne”, smile.

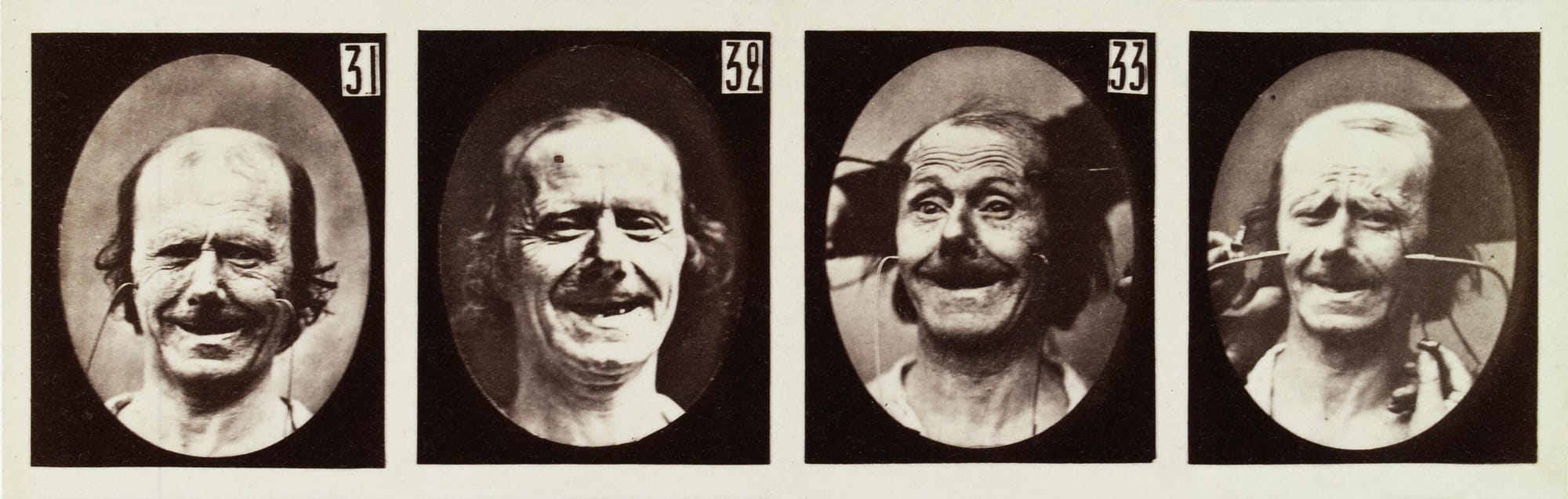

The smile is so-named for the French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne, whose research into emotional expression in the mid-19th century involved administering electric shocks to the face of patients to stimulate the zygomatic major and orbicularis oculi muscles (pictured below).

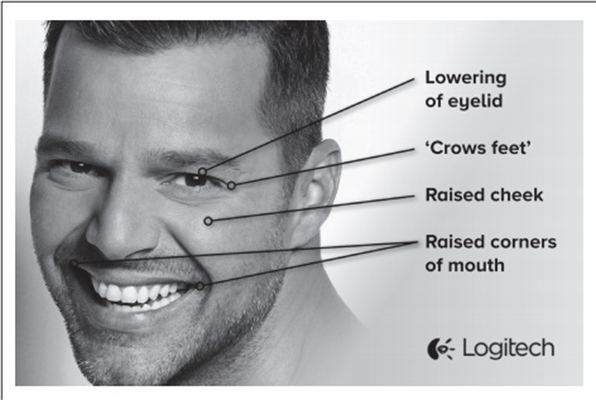

It’s these two facial muscles when working in tandem that produce the distinctive “Duchenne smile” by raising the corners of the mouth (zygomatic major) and lifting the cheeks (orbicularis oculi) to produce crows’ feet around the eyes.

The non-Duchenne smile only uses the zygomatic major muscle and doesn’t reach the eyes.

Duchenne smile to overcome negative celebrity attitude

Jasmina Ilicic is an associate professor in Monash Business School’s Department of Marketing and is researching the influence of facial-feature characteristics on a spokesperson’s effectiveness.

She’s looked at how limbal rings (dark annulus around the iris of the eye) influence consumer perceptions of a spokesperson’s purity, and how freckles and facial asymmetry enhance judgements of the source's authenticity.

Her research finds that limbal rings, freckles and facial asymmetry

ultimately result in spokesperson effectiveness in terms of positive ad attitude, brand attitude and purchase intentions.

She’s recently been particularly interested in the Duchenne smile, and is the lead author on the study "How a smile can make a difference. Enhancing the persuasive appeal of celebrity endorsers".

The study investigated the effect of a Duchenne smile on consumer perceptions of celebrity genuineness, and, in turn, consumer attitudes towards the advertisement and their purchase intentions.

“Even if things go astray and celebrities fall from grace, careful execution of advertising can counteract negative associations held with a celebrity,” Associate Professor Ilicic said.

She said the research showed that consumers will perceive a celebrity to be less genuine when they have a negative attitude towards the celebrity or when they’re exposed to a celebrity displaying a non-Duchenne, or fake, smile.

“When a consumer is exposed to negative or unfavourable information about a celebrity, negative attitudes form towards the celebrity and lower their perceptions of the celebrity’s genuineness,” she said.

“After exposure to negative information, such as complaints regarding tax evasion, advertising featuring the celebrity with a non-Duchenne or fake smile further lowers perceptions of the celebrity’s genuineness.”

But, she said, when the shamed celebrity was featured in an advertisement with a Duchenne smile, there was a discernible change.

“When a consumer is exposed to negative or unfavourable information about a celebrity, negative attitudes form towards the celebrity and lower their perceptions of the celebrity’s genuineness.”

“Even if the celebrity had been embroiled in a scandal, and the consumers had developed a negative attitude towards the celebrity, they perceived them to be more genuine,” she said.

And this, she said, led to consumers responding more favourably to the advertisement and, consequently, greater likelihood to purchase the product being endorsed.

Wider implications

She said the results have important implications for the marketing industry – for advertisers, brand managers, and marketers dealing with negativity surrounding celebrity endorsers.

“These finding suggest simple guidelines regarding the depiction of celebrity smiles in advertising while taking into account prior attitude towards the celebrity,” she said.

“Marketers may feature the celebrity endorser in advertising executions displaying a Duchenne smile to enhance perceptions of the celebrity’s genuineness.

“This will result in positive consumer attitudes towards the advertisement and a greater intention to purchase the branded product, even if prior attitudes towards the celebrity are negative.

“The results of this study mean that premature dumping and replacement of celebrity endorsers may be avoided, saving brands time and money,” Associate Professor Ilicic said.