Wanted: Female, 22–25, for a secretarial role. Prefer single.

Imagine running a job ad like this today. Before the advent of anti-discrimination laws, employers were able to limit applicants to very specific age groups, sex and marital status.

The introduction of Victoria’s Equal Opportunity Act in 1977 drew a line in the sand for sexual discrimination in the workplace. Race discrimination laws existed at a federal level, but state governments brought in legislation to cover issues such as sex, age and disability discrimination.

In 1979, flight instructor and qualified pilot Deborah Wardley took on Ansett Airlines under the new legislation after it refused to employ her as a pilot because of her gender.

Writing to the Women’s Electoral Lobby, general manager Reg Ansett said: “We have a good record of employing females in a wide range of positions within our organisation, but we have adopted a policy of only employing men as pilots. This does not mean that women cannot be good pilots, but we are concerned with the provision of the safest and most efficient air service possible [and so] we feel that an all-male pilot crew is safer than one in which the sexes are mixed.”

Subsequently, the case came before the High Court of Australia and, much to the chagrin of Reg Ansett, Wardley won and went on to a successful career as a pilot.

Not far in 40 years

Fast-forward 40 years and have we really made that much progress?

Monash Business School’s Dr Dominique Allen doesn’t think so.

“The public thinks that discrimination was addressed in the 1980s and that it doesn’t happen any more,” Dr Allen says. “When Deborah Wardley won the case, it was a significant victory for women fighting discrimination in the workplace, but our legislation has really stagnated since then.”

And she says the move to private mediation is the main reason.

Dr Allen explains that in the early days of the legislation, prominent cases such as Wardley's helped weed out the most blatant forms of discrimination and served to educate the public, but since the courts moved towards mediation and conciliation, most anti-discrimination cases are settled privately.

“When Deborah Wardley won the case, it was a significant victory for women fighting discrimination in the workplace, but our legislation has really stagnated since then.”

And there are many reasons why people settle – the exorbitant costs involved, the risk of more costs if you lose, reputation damage and, importantly, the psychological pressures of being involved in litigation.

Most people don’t want to spend years pursuing a claim, and others who have lost their job simply move on and find another one, rather than front up to court.

While this makes perfect sense, it means that the whole system has become privatised — taking place behind closed doors so people aren’t aware that discrimination still happens or how it's resolved.

What does compliance look like?

While settling cases may make sense from a business or employer perspective, they don’t know what compliance looks like, Dr Allen says.

There's no deterrent aspect – they can’t see that someone else has made a claim against a certain issue or behaviour and make moves to prevent it from happening in their own organisation.

“There are problems with the system that focuses on the individual rather than the broader society,” Dr Allen says “We cannot rely on an individual to address the discrimination to 'name, blame and claim' it as discrimination.”

She advocates a watchdog similar to corporate regulators to shift the focus to the employers and to business, because they're best-placed to foresee the impact of their actions on equality.

She says a watchdog could make claims on behalf of people or represent them, in the same way the Fair Work Ombudsman can in industrial relations.

“There’s nothing like the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) or the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) that can step in and enforce the law or pursue a case – it relies on an individual who is often a vulnerable person,” she says.

Other options to improve the system include putting requirements on employers and business to act first, rather than waiting until discrimination occurs. Dr Allen says the UK does something similar; public authorities need to have “due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity” i

n their undertakings.

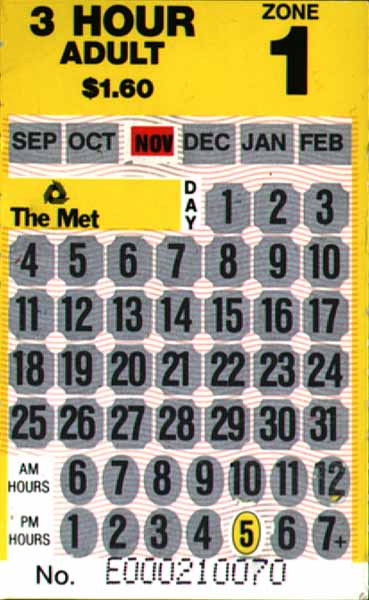

Tickets, please

Another case involved the Victorian Labor government's introduction of scratch tickets in the late 1980s, which were difficult for visually impaired people to use, and the removal of conductors who had traditionally assisted people with disabilities.

The Equal Opportunity Board ruled that the Public Transport Corporation's plan was discriminatory because It affected people with disabilities more severely than the rest of the community.

The ruling was disputed and nine people with various physical disabilities took the case to High Court on the basis that these actions were a form of indirect discrimination. The judges agreed.

Dr Allen says that it was one of the unusual instances where the court ruled that it was not just going to compensate people; it ordered the government to review the ticketing system on trams.

It would be unusual today to see a wide order like this. Now, court-awarded damages are fairly insignificant amounts. Yet Dr Allen says it's one of the things that's needed to tackle discrimination effectively.

She says that while having the conciliation system is good – it saves costs and the deal remains confidential – from a societal perspective it doesn’t address broader issues.

Bring in the stick

From a business perspective, low amounts ordered by courts aren't a deterrent and don’t encourage compliance with the law. Dr Allen says there's "no big stick to wave if people aren't doing the right thing".

"There's no fear, as would be the case if the ACCC was pursuing them, that a hefty penalty may be imposed if they’re found to have acted unlawfully.”

So, in 40 years have we addressed the discrimination in this state?

“I think we have come a long way. There are barriers that have been broken down and blatant forms of discrimination don’t happen any more, but there’s still much more that the law could do to address those hidden systemic forms of discrimination,” Dr Allen says.

Victoria’s legislation was modernised in 2010, and Dr Allen's current research is assessing how effective these changes have been. Her findings are due later in the year.

This article was first published on Impact. Read the original article