On April 24, 1918, Australian troops advanced 2700 metres in the dark without artillery support to retake the small French town of Villers Bretonneux. The surprise attack took place on the eve of the third anniversary of the Gallipoli landings.

Gallipoli veteran John Monash later said that “Villers-Brettoneux marked the crisis of the war. It gave the Allies breathing space, enabled the Americans to arrive, and paved the way for the August offensive.”

On Anzac Day in 2018, the Sir John Monash Centre was opened at the Australian National Memorial near Villers Bretonneux in France to commemorate the centenary of that decisive action on the Somme; 2400 Australian soldiers lost their lives fighting for the town. Their sacrifice continues to be remembered in Villers Bretonneux, where the local school, L’Ecole Victoria, was built by donations from the people of Victoria in 1920 (the townsfolk in turn raised $20,000 towards building a school in Strathewen that was destroyed in the Black Saturday bushfires).

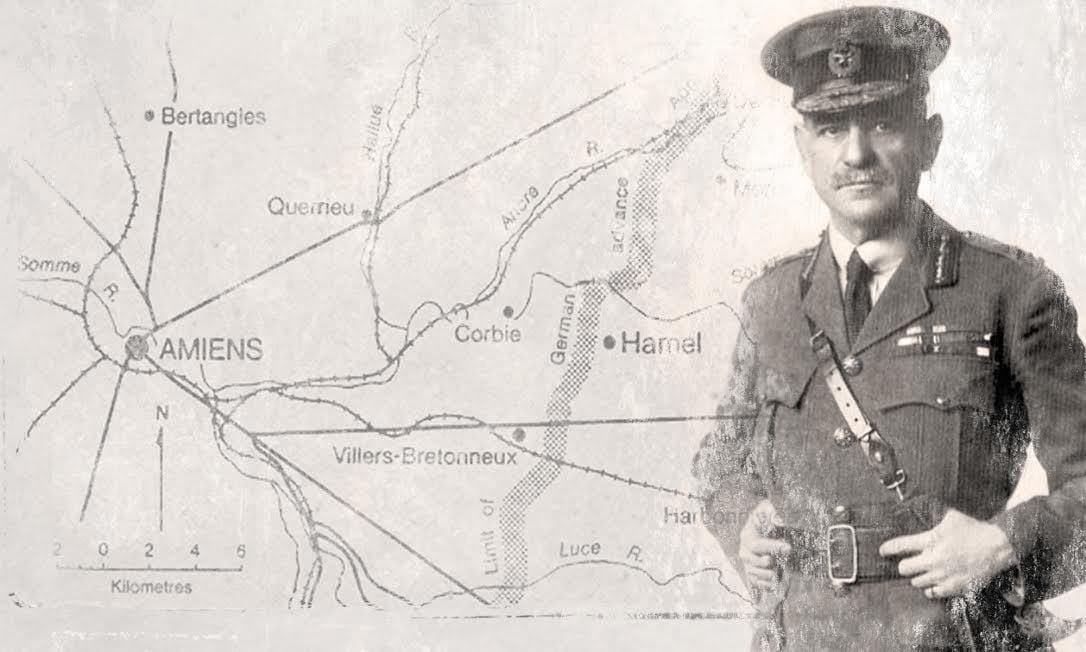

The Sir John Monash Centre forms the hub of the Australian Remembrance Trail along the former battle sites of the Western Front. The victory at Villers Bretonneux was followed by the Battle of Hamel on July 4, 1918, a textbook military operation meticulously planned by Monash. Hamel was Monash’s first battle as commander of the Australian Army Corp (a promotion he received after Villers Bretonneux was taken). At Hamel, parachutes were used to drop medical supplies, and tanks to replenish supplies on the lines and to protect the infantry – innovations that aided the victory, saved lives and were later adopted as standard procedure.

But Monash’s greatest triumph was on August 8, 1918, when the five Australian divisions under his command formed the spearhead of a massive Allied offensive against the Germans at Amiens. This breaching of the German defences was the beginning of the end of the Great War. Four days later, on August 12, Monash was knighted by King George V. It was the first time in 200 years that a British monarch had knighted a military commander on the battlefield.

Monash was more than a soldier. He received his military training while serving as an officer in the militia, a post he held while also building his career as an engineer. When World War I began he was 50 years old – he first saw active service at Gallipoli. When the war ended, Monash was the highest-serving Australian army officer and was responsible for demobilising and repatriating the Australian troops.

On his return to Melbourne, Monash secured Victoria’s growing need for reliable power as chairman of the State Electricity Commission. When he died in 1931, almost 300,000 people gathered to attend his state funeral, believed at the time to be the largest crowd to attend such an event in Australia.

In his entry on Monash in The Australian Dictionary of Biography, the historian Geoffrey Serle describes Monash as “one tall poppy who was never cut down”.

He writes that by the 1920s, Monash was broadly regarded as “the greatest living Australian”, accepted by the community as a “seemingly unpretentious outsider, not really part of the Establishment”.

“His commanding intellect was sensed, as well as his basic honesty and decency … No one in Australia's history, perhaps, crammed more effective work into a life; but, he said, work was the best thing in life.”

Monash was born on June 27,1865, in West Melbourne, to German-Jewish parents. He studied law, as well as engineering, and was in 1912 elected president of the Victorian Institute of Engineers. He was also an accomplished pianist. In 1884, he enlisted in the Melbourne University company 4th Battalion Victorian Rifles.

During World War I, rumours circulated in Melbourne, London and Cairo that he was a German spy, and the war correspondents Charles Bean and Keith Murdoch plotted secretly against his promotion.

In his book Monash: The Outsider Who Won a War, biographer Roland Perry asks: “How and why did John Monash, the classic outsider, overcome these obstacles and reach a position that allowed him to play a major role in winning World War One? How did such a gentle individual, regarded as a Renaissance man, with his philosophical outlook and love of music, theatre and literature, develop one of the toughest minds of the war?”

Military historian P. A Pederson, who wrote Monash as Military Commander, would have quarrelled with the assertion that Monash “won the war”. Yet he says that Monash’s “technical mastery of all arms and tactics, particularly surprise and deception, was unsurpassed among his contemporaries”.

By the time he reached the Western Front, Monash was removed from the action in the trenches, but this was not the case at Gallipoli, where, according to Pederson: “The peculiar circumstances of command” meant that “senior officers faced the same dangers as their men”, he wrote.

Monash witnessed the slaughter first-hand and saw “the effects of a last-minute change of plan, which left his brigade without adequate military support … Above all, he learned the limits to which men could be pushed. The sight of sick and exhausted soldiers responding to yet another call was extremely important in the context of the demands he made on the Australian Corps in August-October 1918.” At Amiens, Monash made sure that his men received hot meals on the front line.

It's an irony of history that the university that bears Monash’s name first achieved national prominence for its student anti-war protests during the Vietnam era.

The Monash Faculty of Engineering, the largest in Australia, is a leader in renewable energy research, designed to end our dependence on the coal-fired power stations that Monash helped develop.

Roland John Perry OAM is a Melbourne-based author and Monash graduate best known for his books on history, especially Australia in the two world wars. His latest work, Monash and Chauvel: How Australia's two greatest generals changed the course of world history, tells the story of the emergence and dominance of these brilliant Australian soldiers, who commanded the two most effective armies in defeating the Germans and the Turks in the Great War.