We often hear that we are living in a corrupting, visually saturated, consumer culture, which threatens the innocence of girlhood. But representations of young girls in the European postcard trade at the turn of the 20th century cast doubt on the notion of an ideal, more innocent past.

From the mid-1890s until World War I, Europeans had a love affair with collecting postcards. Created in 1874, the Universal Postal Union established standardised postal regulations at accessible rates for its member nations; this greatly contributed to the postcard craze. In bigger cities, cards needed just a few hours to arrive at their destinations. The world was at one’s fingertips.

Rival publishers vied for attention with collectors’ competitions, impressive exhibitions, and artistic innovations. It didn't take long for alluring postcards to flourish in the light-hearted social context of the time. European publishers showed great ingenuity in avoiding local censorship. They played with the boundaries of what was socially and legally acceptable.

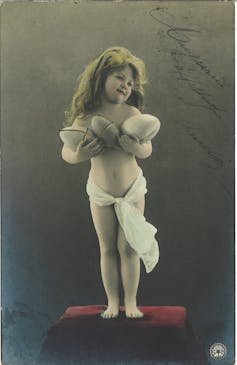

Yet the trend of erotic postcards did not just bring cheeky smiles and cheerful eroticism. A quick look at one Italian postcard (c.1900) highlights more disturbing aspects. Elevated on a pedestal, a pre-pubescent model is the privileged object of our gaze. Side lightings magnify her blonde mane, and sculpt her flawless skin. A neutral backdrop focuses the attention on her statuesque body. This little goddess is a work of art.

Let us study the precise nature of this ideal.

Three eggs hide the poser’s bosom. They allude to the symbol of fertility, while playing with the visual resemblance between the shape of breasts and eggs. A deftly positioned piece of cloth emphasises her hips thereby defining an inviting triangle. This veil of modesty also denotes the art of teasing in a game of hide and seek.

The artist tainted the model’s lips with a vivid red, a similar hue to the plinth’s velvet. The colour conveys a brazen sexuality immediately contradicted by the candour of the model. What strikes one’s attention is precisely the discrepancy between these sexual innuendos and the sitter’s youthful naivety. She proudly smiles, unaware of the paedophilic gaze she may entice in the adult viewer. The end result is deeply unsettling and exploitative.

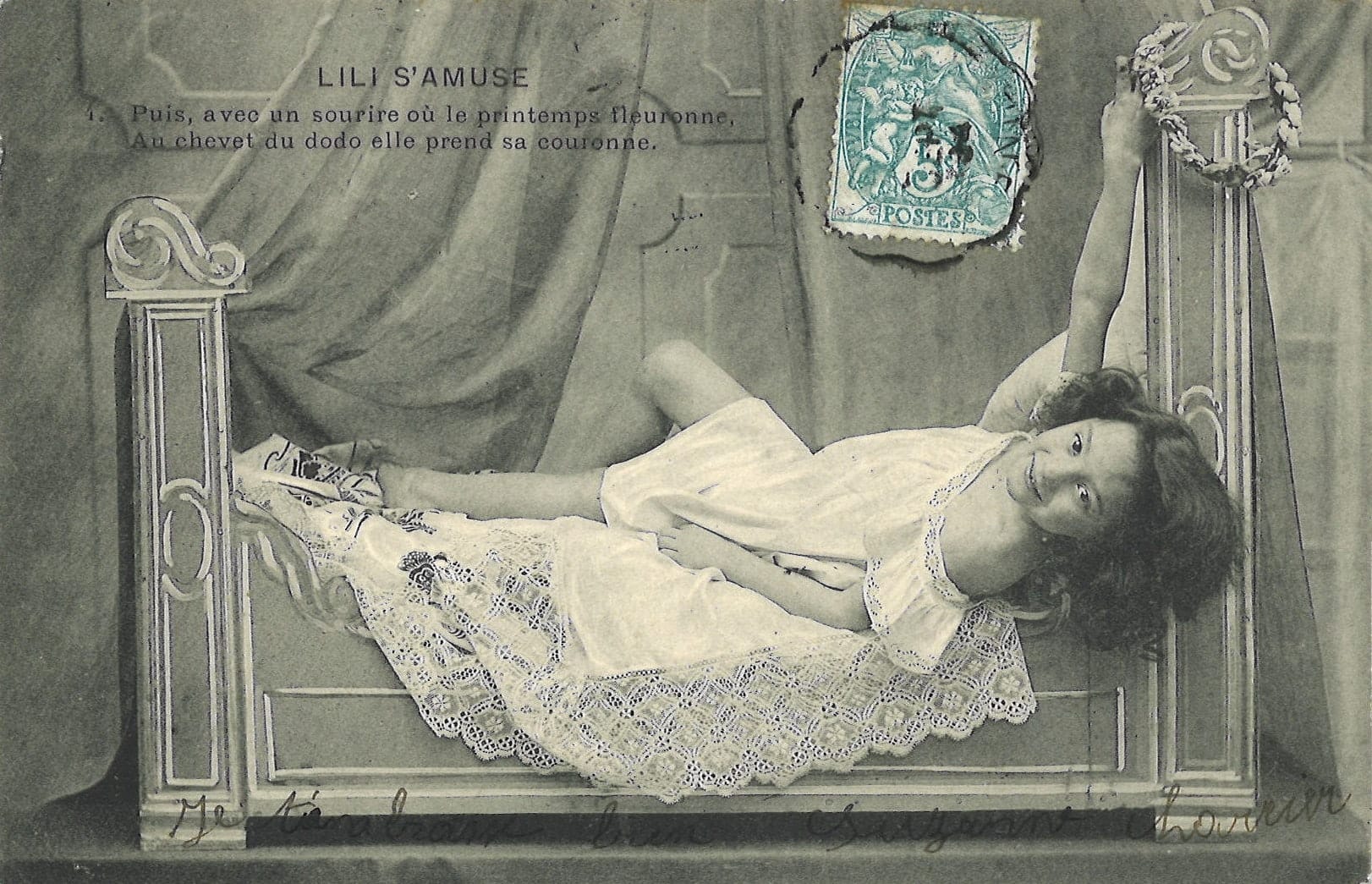

In another unattributed French postcard (before 1904), we follow the adventures of Lili, who's described as “playing around”. The caption informs us that she has a springtime smile, and that she's ready to wear her bedside wreath. Her white apparel and the laced clothing convey the idea of virginal innocence and freshness.

Still, her inviting pose, coquettish manners, and bare shoulder leave the viewer perplexed. There is an uneasy tension between the artificiality of the setting and the model’s impression of spontaneous cheerfulness. It is difficult not to read in this staged vignette an eroticised performance for adults at the expense of the young model.

The ‘erotic virgin’

In both postcards, the sitters epitomise the photographers’ quest for both pristine morality and brazen sexuality. The ambivalent girl exemplifies what scholar Hanne Blank names, the “erotic virgin”.

In her book, Virgin: The Untouched History, Blank highlights a recurrent theme in pornographic tropes: “the tale of the skilled ‘conversion’ of resistant virgin into willing wench”. In these coded scripts, virgins hold a dormant sexuality ready to be activated by “the magic of the ‘right’ male wand”.

Blank links the modern fetishising of virginity to the rise of capitalism during the industrial revolution. Young girls left rural areas with the hope of finding better prospects in the city. Economically and socially vulnerable, they were easy prey for unscrupulous employers and brothel owners. The temptation of a pristine body was even greater as venereal diseases were rampant.

The burgeoning mass-media culture played a pivotal role in establishing the virgin as an object of sexual lust. As the possibilities of reaching a wider audience increased, so did the virgin’s lucrative potential. By drawing on the dual characterisation of female sexuality as virtuous and vicious, the industry capitalised on fantasies of both innocence and experience.

This new eroticised visual culture drew the attention of legislators, philanthropic organisations, and religious groups. Concerns of child protection reformers ranged from the growing recognition of the child as a vulnerable being in need of protection to a more general fear of moral corruption.

Still, photographs of coquettes were risqué yet charming. Under the celebration of a candid femininity, they catered for both male and female audiences. More than a marginal phenomenon, the sexualisation of girlhood in the social fabric denotes a collective fascination with the young body as a modern ideal of femininity.

A socially ingrained phenomenon

World War I sounded the death knell of the postcards age. During the conflict, propaganda postcards had helped feed the nationalistic fervour, but overall, demand for postcards plunged. The attraction of youthful femininity, though, did not wane. Another medium offered more exciting prospects and creative potential than serialised postcards: the cinema.

Tendentious 19th-century postcards, Brooke Shields’ auctioned virginity in Louis Malle’s movie Pretty Baby (1978), and virginity pornography pervasive on the internet, all create the same sexual scenario. Their protagonist has been a little Eve who tempts Adam in the Garden of Eden.

Though technology evolves constantly, the sexualisation of girlhood is a socially ingrained phenomenon, and the commodification of the female being as virgin and whore remains unchanged.

This article was first published on The Conversation.

Elodie Silberstein receives funding from Monash University for a graduate research scholarship. She's a member of the Darebin Women’s Advisory Committee (DWAC), which provides guidance to the City of Darebin on gender policies.