The car – that great Australian symbol of identity – has been the main image of Victorian manufacturing for decades. The factories in Geelong, Broadmeadows, Altona and Port Melbourne churning out Holdens, Fords and Toyota-hybrids became part of the physical and psychological landscape.

Toyota in Altona is now down from 4000 workers to 1300, who remain employed but not in manufacturing. The plant's closure comes a year after the last Australian-made Ford vehicles rolled off Victorian assembly lines, ending 90 years of car-making. Holden announced four years ago that it would wind up its Victorian and South Australian vehicle and engine manufacturing, a process which is now (as of this month) complete.

But reports of manufacturing’s imminent demise are premature, even though car-making has slowed to a trickle.

“Victoria’s manufacturing sector is going through a transition,” says acting state minister for small business, innovation and trade Marlene Kairouz, “but it is certainly not dying.”

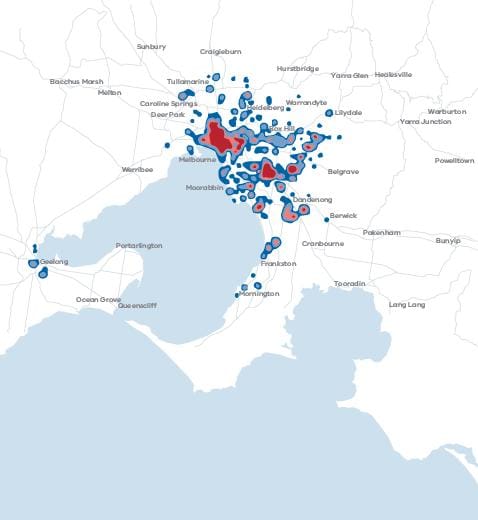

Pharmaceutical and medical technology manufacturing is now worth almost $13 billion – which is around half of the state’s entire revenue from the manufacturing sector. It employs more than 20,000 people mainly in metropolitan Melbourne.

The new Medicines Manufacturing Innovation Centre (MMIC) is based at Monash University’s Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Parkville. It is a joint venture between Monash, the State Government and the private sector (manufacturers) to grow exports of medicines made here, and support those who make them.

“MMIC provides clients with access to world-class infrastructure and a multidisciplinary team to deliver economic impact and competitiveness,” says centre director, associate professor Michelle McIntosh.

“Our aim is to help the Victorian manufacturers be really competitive and if need be transform to more advanced manufacturing capabilities. Instead of just doing tablets or capsules, for example, we might be able to move them into, say, vaccines.”

The genesis of MMIC was a trial partnership with drug-maker Glaxosmithkline (GSK) six years ago at a time when its Victorian operation – a large factory in Boronia – was under threat of closure.

Monash’s Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences helped the company with research and development, and the factory was able to remain open with 500 jobs saved. The fledgling partnership eventually came up with world-first ‘Blow-Fill-Seal’ technology for temperature sensitive products such as vaccines.

Now MMIC is like an “open-access” scheme, says the institute’s head, Professor Bill Charman.

“We are like the fulcrum, the common denominator. We can bring companies together, and we can encourage them into more specialist manufacturing. This is really just the next version of what we started with GSK. I can see a bright future for manufacturing.”

It is what Professor Charman suggests – open-access. Anyone pharmaceutical or med-tech manufacturer can theoretically become involved and benefit from the networks MMIC provides. It can provide specialists to work with companies in-house for the duration of a project, for example, without the threat of them being pulled back onto other work.

Exports of pharmaceutical goods from Victoria rose to nearly $1.5b this year, with the growth driven by blood products to the US and medicines to China. The state government has prioritised pharmacy and medical technology as “key priority growth sectors”.

Other growth areas in manufacturing are food and beverages, steel and chemicals.

The pharmaceutical sector is “growing fast,” says acting state minister Kairouz, and has developed a booming reputation “thanks to our highly skilled workforce and culture of innovation”.

PHARMACEUTICAL AND MEDICAL TECHNOLOGIES SECTOR

Revenue $12.7 billion

Sector value-added $2.2 billion

Exports $1.35 billion

Percentage of Victoria's total state exports 3.5 per cent

Total capital investment $276 million

Number of employees 23,000