The tawny coster is a medium-sized, very pretty butterfly with deep orange-coloured wings bordered with black, and black and white spots. Underneath, it’s muted orange (males) or yellow (females), although in Australia these colours have been seen reversed. It flies slowly, lingers on flowers, favouring the passionfruit family.

It has “charisma”, which in biological sciences means the tawny coster’s (Acraea terpsicore) colours and movement make it able to be photographed or documented reasonably easily.

And if it can be photographed – especially by citizen scientists – it can be uploaded to online portals and social media and used by science for good.

These “charismatic” species then attract broader interest from the public because of their looks and, because they’re more visible, they can increasingly help real scientists a lot more in tricky research regarding migration, conservation, habitat, evolution and the environment.

Calling on citizen science

Monash University’s Dr Shawan Chowdhury, who runs the Global Change Ecology Lab at the School of Biological Sciences, has led a team using exactly this kind of citizen science to study how the invasive butterfly – native to the Indian subcontinent – has expanded its “geographic range” out of the subcontinent into Asia and Australia.

Since the 1980s, the tawny coster has expanded into the subcontinent and neighbouring countries including China, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. It was first spotted in Australia, near Darwin, in 2012.

The lab’s previous study looked closely at Australia and showed the butterfly had expanded, or moved, at approximately 135 kilometres per year from the Northern Territory into Queensland.

The newest research on this butterfly by the large international team is published in Conservation Biology.

It shows that combining data from online platforms, such as Facebook and Flickr , and conventional biodiversity databases, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, which includes data from museums and citizen science applications (such as iNaturalist), can significantly improve what we know about biodiversity distribution.

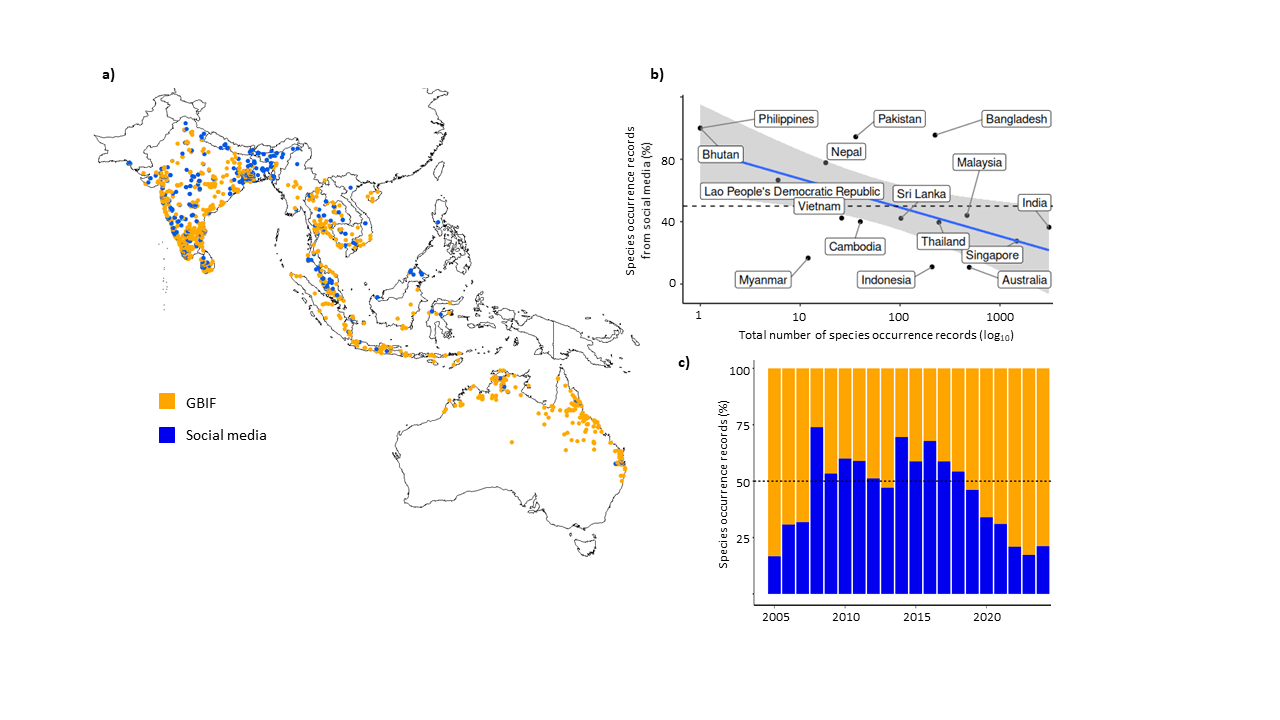

When the research team combined global butterfly records from the GBIF with geotagged social media sightings, social media data drove a 35% increase in total species distribution records.

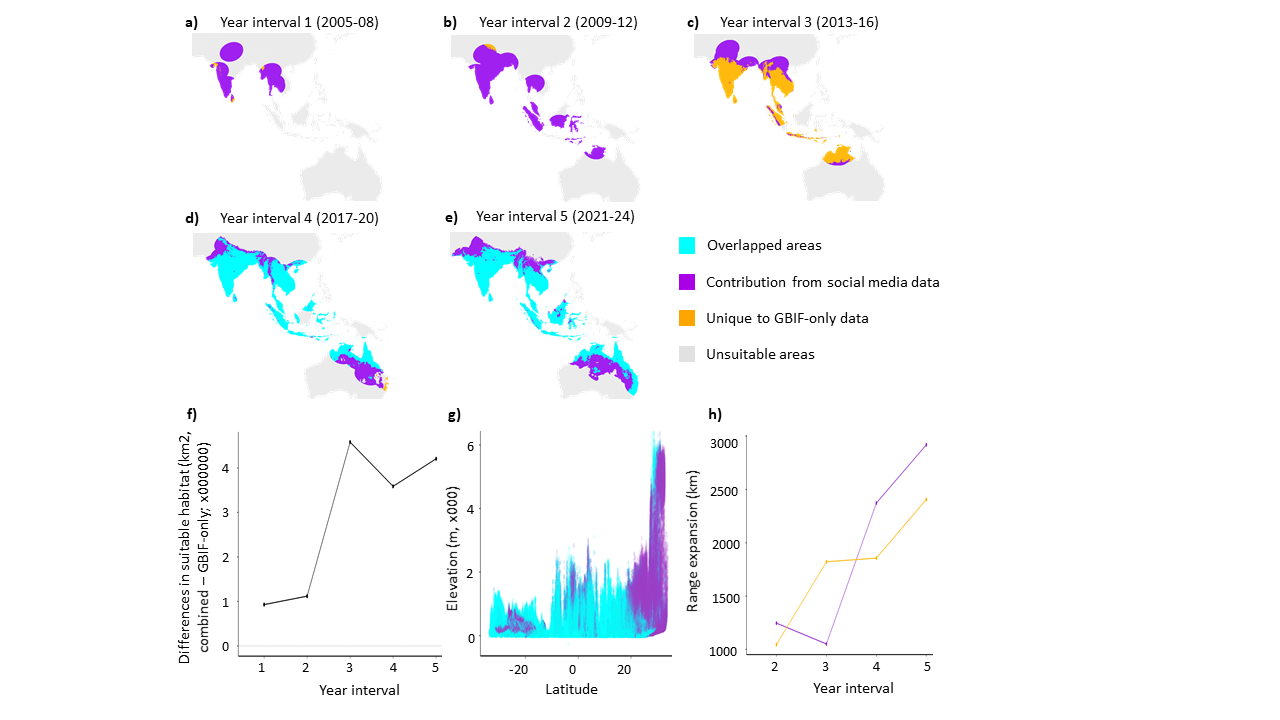

The combined data improved model performance and estimated range expansion, and often provided faster, broader and more detailed information on species range than traditional sources.

In some years, the range expansion rate predicted from the combined data increased by hundreds of kilometres.

Distribution recorded in real time

The research shows that the main database of records, via GBIF, when used alone, “systematically underrepresented areas in the leading edge of the expansion, especially areas with cooler maximum temperatures, lower rainfall and higher elevations – environments that may be critical for species survival under climate change”.

The researchers say social media and online sites could become even more helpful in tracking invasive species and recording their distribution in real time. Another recent study led by Dr Chowdhury showed that incorporating locality data from Facebook helped understand the distribution of 67% of invasive species in Bangladesh.

“This highlights the potential of such data for tracking the arrival of new invasive species,” Dr Chowdhury says.

He says citizen science can fill major gaps, especially from countries underrepresented in biodiversity databases, to “improve our understanding of biodiversity redistribution” for conservation.

“It’s a powerful reminder that conservation science can’t afford to ignore citizen observations. Social media isn’t noise, it’s data. And, often, it’s the kind we need most.

“I was really surprised at the results. People are very interested in this kind of thing, and the citizen scientists are often very competitive in recording the highest number of species or taking better photographs.”

Better tech and online sites fuel the boom.

Why Australia?

Why the tawny coster comes to Australia is another question. It could be natural expansion, Dr Chowdhury says, but researchers think loss of habitat or environmental or climate-related reasons in their native countries could lead to such rapid movement.

Many butterfly species seasonally migrate, often stopping at plants for food, but habitat loss means the stops may change or have already changed.

James Cook University research in 2018 looked at data regarding the butterfly’s first appearance on the east coast of Australia, in Cairns, coinciding with winds produced by Tropical Cyclone Debbie.

Despite the tawny coster now spreading across Australia, including Canberra, it’s not yet been declared a pest and has no recorded economic impact.

It’s considered a pest species in some places, such as Sri Lanka, where it’s native but harmful to plants in the Cucurbitaceae family, which includes pumpkins and zucchini. An invasive alien species is both non-native and harmful.

There’s an unknown impact of the butterfly in Australia so far, but as the paper states, “expansion into new ecological zones raises red flags for native ecosystems and long-term biosecurity”.