The events of January 2026 exposed dramatic evidence of the strain on the international order that we’ve known since the end of the Cold War. Indeed, we may be watching its demise in real time.

As what we formerly knew as “the West” bends and contorts under pressure from within, something called the “Anglosphere” also came under strain, leaving Australian strategists with core assumptions to examine and some hard choices to make.

Times, they are a-changin’

One of the great things about the period of university shutdown over Christmas and the new year is the absence of emails and the ability to really switch off.

Not so the rest of the world, however. Imagine my surprise as I put down my Bryce Courtney novel and pina colada and picked up my phone to find that the US had attacked Venezuela, threatened to annex Greenland and that the global elite at Davos had declared globalisation to be over.

For anyone who would like to hear Mark Carney’s outstanding Davos speech in full here it is. This is what true global leadership looks like.

— 𝔗𝔯𝔲𝔱𝔥 𝔐𝔞𝔱𝔱𝔢𝔯𝔰 (@politicsusa46) January 20, 2026

Canada should be immensely proud today, because they are leading the fight back when others dare not.

🎥 TikTok - https://t.co/BExGV2YIDq pic.twitter.com/QTef90Ceo4

All the while, the Iranian regime teetered on the brink of collapse, the conflict in Gaza continued to reverberate around the world, not least in Australia, and the war in Ukraine surpassed the amount of time it had taken the Soviets to beat Nazi Germany.

Notable in this whirl of events was the impending demise of NATO, as the Trump-led US threatened to annex Greenland from its NATO ally, Denmark.

Famously, an attack on one NATO member is considered an attack on all. A US annexation of Greenland would have been a strategic own-goal because it might have seen NATO powers forced to defend each other from an attack by the key member of the alliance, effectively ending the institution that had done more than any other to structure the international order since 1945. NATO 0 - 1 Russia.

“Under Trump, America is on the brink of becoming the enemy, not our most important ally.”

— Times Radio (@TimesRadio) January 19, 2026

Andrew Neil is chilled by Trump’s mission to become “imperial overlord of the whole Western Hemisphere.”@AFNeil | #TimesRadio pic.twitter.com/OLzw4eOjMF

This outcome was avoided because the European NATO powers, plus Canada, realised the limits of flattery and acted against the US. Many have concluded that the West as we knew it is over.

But what of that other related idea, the Anglosphere?

The Anglosphere and global order (English-speaking people; Anglo-Saxonism)

The “Anglosphere” is a way of viewing the world that scored some significant success in the previous decade, including Brexit and AUKUS.

It’s an elite project that asserts that the world is a safer and better place when English-speaking powers – usually seen as the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – act in concert to shape the global order.

This is sometimes referred to as “Anglobalisation”. Its advocates are in very much favour of free trade as a foundation for political liberty. Furthermore, they suggest that human rights can be traced back to significant moments in English history, notably the sealing of Magna Carta, which were then spread around the world.

Of course, others disagree with this view of the legacies of the British Empire and US hegemony during the 20th century.

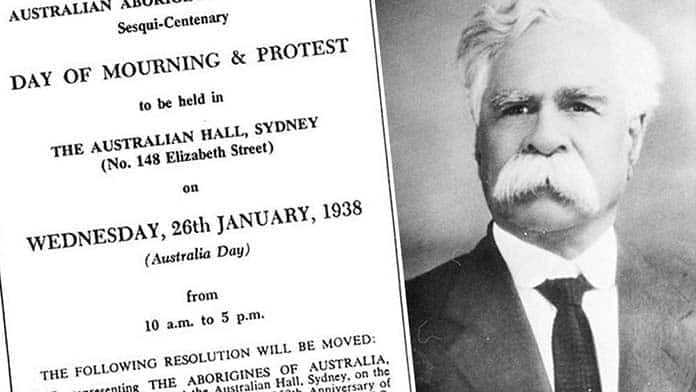

In fact, one’s view on whether the British Empire and the “American Century” were “good things” tends to determine one’s view on the Anglosphere. This is because the Anglosphere has certain genealogies that link it to ideas grounded in 19th and 20th-century racism.

The first of these is Anglo-Saxonism, which suggested that nations built substantially on Anglo-Saxon stock had a genius for government (and hence ought to govern others).

The second was the notion of the English-speaking people – popularised by Winston Churchill – that suggested it was the Anglophone powers that held murderous totalitarianism in check in the first half of the 20th century and made the world safe for democracy.

This logic was extended by leaders such as Ronald Reagan and Maragaret Thatcher, to the ultimately successful confrontation with Soviet communism up until the end of the Cold War in 1990.

Contemporary geopolitics and the Anglosphere

All seemed well as we entered the 21st century, but the second presidency of Donald Trump introduced trouble into this English-speaking paradise.

The relationship between the Anglosphere and the West is in some tension. One thing the Anglosphere advocates and the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement shared was a disdain for Europeans.

This came out in Brexit, and MAGA’s amplification of longstanding US calls for NATO members to contribute more to the defence of Europe. The disdain for Europe also brought MAGA into alignment with the far-right in Putin’s Russia.

But there are intra-Anglosphere tensions that MAGA has brought to the surface.

Trump may be the erratic figurehead for the MAGA movement and appears increasingly incoherent and deluded, but the people behind him have a plan and are executing it.

This plan releases the US from all obligations. It seems to have a higher regard for English-speaking countries than others, but only if they reject so-called “cultural erasure” through immigration and align with the white supremacist worldview to be found in MAGA.

The Anglosphere and the Lucky Country

It might be comforting to think that Australia is immune to all of this, especially given the good deal that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese sealed with the Trump administration in 2025. Trump seemingly likes Australia (with the exception of Kevin Rudd), but Australia cannot ride its luck with the MAGA US for too long.

An agreement with Trump can easily be rescinded by the man himself who the US system, famous for its checks and balances on executive power, seems unable to contain. The presidency is run like a court and opinions can change quickly, so Australia could soon find itself on the outer, like Canada and the UK.

But the greatest strategic danger for Australia lies in MAGA’s hostility to China, Australia’s main trading partner. With AUKUS, the Morrison administration effectively bound Australia to the US in any action it may take against China, probably over Taiwan, and well before the nuclear-powered submarines arrive in Australian ports (assuming that they are of strategic value).

The Labor government hardly demurred. But this foundational belief in the US as the security provider in the Indo-Pacific should be re-examined by strategists in Canberra in light of the direction of the MAGA USA.

The changing world order cannot be seen as the “madness of King Donald” alone. Australia has nestled in this Anglophone world since 1788, but this cannot – nor should – be taken for granted. It’s time for new thinking in Canberra, one that seeks alliances with truly like-minded middle powers.