Opening this month, the Melbourne Metro Tunnel is a 9km twin tunnel between South Yarra, Melbourne CBD and South Kensington, and includes five new underground stations in central Melbourne.

It represents the largest upgrade of public transport in Melbourne since the City Loop more than 40 years ago and was Australia’s largest infrastructure project when it was first developed, costing $A12.8 billion (in 2025).

While the implementation of the project is the result of the dedicated work of thousands of planners, designers and engineers, the project itself was conceived by the Faculty of Engineering at Monash University through the work of Professor Graham Currie, Director of the University’s Public Transport Research Group.

The tunnel idea was developed as part of a contract research “think-piece” commissioned in 2005 by Melbourne City Council, who asked Professor Currie to investigate new transport alternatives to maintain city access into the future.

The report, Melbourne Future Transport Options (December 2005) outlines the significant problems of growth facing Melbourne, the resulting traffic congestion and the need for higher-quality rail alternatives for access to the CBD into the future.

A concept to create links and increase capacity

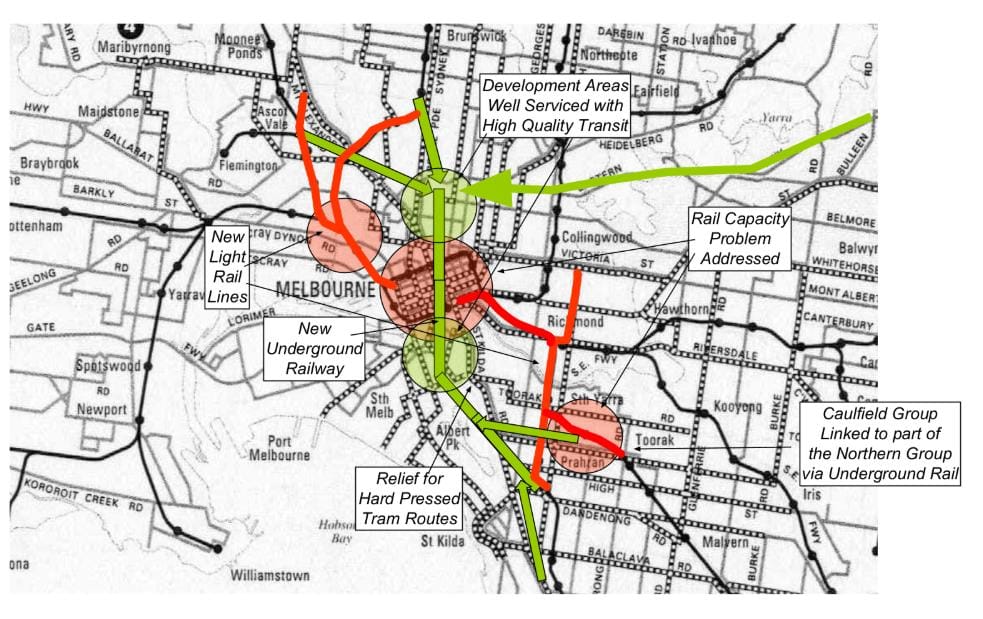

Originally called the North-South Underground Project, the concept was to link the two largest groups of railways in Melbourne – the Caulfield Group (all trains running through Caulfield Station) with the Northern Group (all trains running through North Melbourne Station), via a new underground tunnel.

The rationale was to create substantial new capacity for rail services in inner Melbourne, effectively freeing up rail capacity in the existing City Loop tunnels and providing a new tunnel that doubled the capacity of the City Loop.

In addition, by directly linking Melbourne’s two largest rail groups, passengers travelling between Melbourne’s east and northwest would be provided with a direct trip, removing the need to transfer in the city.

The project would also provide new underground rail stations in inner Melbourne, including important nodes such as Melbourne University.

Professor Currie says “previous thinking on Melbourne’s future public transport was just too small-scale – they weren’t thinking big enough for the problems Melbourne was facing in its future”.

Metro rail has the highest capacity of all modes of travel, which is why all the world’s “mega cities” seek to develop metro systems. However, such systems are very expensive, and Melbourne decision-makers were very reluctant to make investments of this scale on rail.

“The Metro Tunnel idea was therefore carefully designed to be very cost-effective, as it targets the ‘80-20’ rule”, says Professor Currie.

Some 80% of all users travel in inner Melbourne, so benefits are spread among a high share of the market. But the new tunnel is relatively short, as the inner city is quite a small area. So costs are relatively lower, but spread over a high share of Melbourne.

The image below shows the original concept plan from the 2005 report, illustrating the general form and alignment of the tunnel that has now been completed.

Undeveloped concept aspects now make sense

However, the concept also has a number of parts that weren’t developed. One is the tunnel alignment with a possible station in Southbank/South Melbourne and exploring the possibility of linking the tunnel to the Sandringham Line in the south, and new possible lines to Melbourne’s north and east at the northern end of the Tunnel.

The concept plan was also seen as a way to enhance and relieve pressure on inner-Melbourne tram services, seeking methods to provide better-quality right-of-way for trams, including running trams on any rail rights-of-way that were freed up as a result of the Metro Tunnel.

Only the Metro Tunnel aspects of the original concept were implemented. Professor Currie says “these omissions make a lot of sense, given the changes that occurred since the original concept study”.

Melbourne’s growth forecasts are even higher than those expected in 2005, with substantial rail crowding making the capacity benefits of the tunnel the major priority.

“This doesn’t mean some of the wider ideas in the 2005 study couldn’t be implemented in future as needs and opportunities arise.”

Following the 2005 Monash study, The Age newspaper reported on the Monash concept. Professor Currie subsequently presented the tunnel idea in a number of community presentations, and a range of community stakeholders backed the proposal.

In 2008, transport planner and world-leading engineer Sir Rod Eddington was asked to develop an independent report including a review of the tunnel, recommending it be implemented to increase rail capacity. The tunnel was subsequently incorporated into government policy, with construction commencing in 2017.

The value of engineering research

Professor Currie believes the development of the Metro Tunnel concept is a shining example of engineering’s value in universities.

“The world has significant emerging challenges, and the purpose and rationale for engineering research is to find practical solutions to these problems for sustainable and liveable cities of the future.

“At the time of the 2005 study, many thought a new Metro Tunnel was too radical an idea for Melbourne, but in the context of today’s confirmed growth the project now seems sensible,” he says. “Perhaps by 2050, when Melbourne’s population reaches the size of London today, we’ll wonder why we didn’t invest in more rail projects of this kind earlier.”