Climate change is making conventional farming harder, but it could also increase the demand for dried fruit as a more sustainable and resilient food option.

Water scarcity and extreme weather events have always been major challenges for growing crops, but climate change is making these issues even more urgent on a global scale.

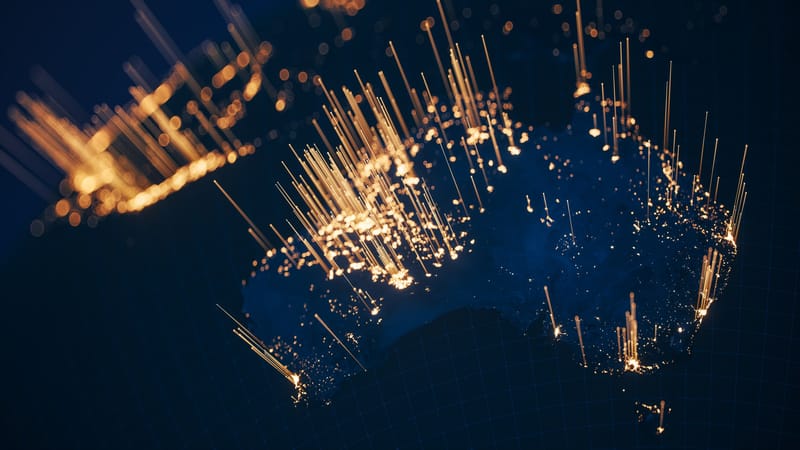

Take Australia, which is known for its dry and hot conditions – about 10 trillion cubic metres of water are used annually to grow crops like cotton, wheat, and barley. That’s enough to fill Sydney Harbour nearly four million times over.

While many introduced crops struggle in Australia’s climate, native plants have adapted over millennia and thrive in it, and their resilience offers valuable lessons for sustainable agriculture.

Among these are Australian native fruits (ANFs) such as finger limes, Kakadu plums, riberries, quandongs, and muntries. These plants have evolved to make the best use of infrequent rainfall, making them naturally suited for a warming world.

Muntries, for instance, grow in the sandy soils of Portland and the Little Desert in Western Victoria – a region recently impacted by devastating bushfires. Their adaptability could be the key to climate-resilient farming practices.

Meanwhile, dried fruits are gaining global popularity as a sustainable and nutritious snack, with the market expected to reach US$14 billion by 2034.

Alongside this, native foods are gaining recognition globally. In Australia, they’ve been championed by chefs such as Mindy Woods and the late Jock Zonfrillo, whose work on MasterChef Australia helped introduce ingredients such as finger limes, wattleseed, and Kakadu plums to wider audiences.

Incredible meal at Karkalla Byron Bay with exquisite native Australian native foods. Australia’s first Aboriginal hatted chef Mindy Woods Bundjalung woman ✊🏼#foodie pic.twitter.com/dtpT231Ccy— Annie E @Chiefdisrupter@aus.social (@ChiefDisrupter) July 9, 2023

This growing appreciation reflects a broader shift towards a new palette of Indigenous and climate-resilient ingredients in modern cuisine.

Dried fruits can retain essential vitamins and minerals while reducing food waste, making them an ideal option for more sustainable diets.

However, one challenge for ANFs is that their preservation methods are not as well understood as those of common dried fruits such as grapes, bananas, and apples.

Extending their shelf-life while retaining their unique nutritional and sensory qualities is critical for making them more accessible.

Unlike introduced crops, ANFs are higher in protein, complex carbohydrates, and antioxidants, offering superior health benefits.

First Nations Australians have long valued ANFs such as muntries, with Traditional Owner knowledge passed down by the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia, and Jupagulk people.

Dalki Garringa Native Nursery is an example of a place where you can find this traditional ecology practised. This cultural knowledge, when integrated with modern scientific practices, can provide valuable insights into sustainable food production systems that can be adapted globally.

The Australian native food industry is growing rapidly, projected to reach A$160 million this year, and thousands of finger lime trees are being cultivated in California and Guatemala.

As climate change disrupts global food production, resilient crops like ANFs offer a sustainable solution for feeding growing populations with fewer resources. This trend reflects a broader shift towards agricultural innovation aimed at ensuring food security in a rapidly changing world.

A shift towards more sustainable agriculture and food processing that can handle climate change and feed more people with fewer resources is essential.

At Monash University’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, we’ve been researching how ANFs preserve, as well as how they’re so drought-tolerant. This is crucial to understanding how to make the way we grow and process foods more sustainable.

Our latest research reveals a critical and fascinating key survival mechanism – ANFs can tap into stored energy more efficiently in hot, dry conditions, giving them a distinct advantage over other crops.

This resilience not only helps them thrive in extreme environments, but also holds exciting potential for improving food processing and extending their product shelf life.

Through various drying methods, we’ve observed a unique property in ANFs – after drying, they bind water more strongly than other fruits.

Compared to apples, for instance, muntries have nearly twice the drying time and water binding strength.

Our discovery could have far-reaching implications for food processing innovation. Understanding optimal drying conditions in ANFs ensures minimal energy use, lower processing costs, and maximum nutrient retention, helping to scale up cultivation and make these sustainable crops more affordable.

Our findings also contribute to broader knowledge about climate-resilient agriculture, ensuring Australia and other arid regions can continue producing food despite changing environmental conditions.

As climate change reshapes global agriculture, we must rethink how we grow and process food. By leveraging Australia’s native fruits – both for their resilience and their nutritional benefits – we can create a more sustainable and climate-adapted food system.

ANFs could play a crucial role in securing food supply for future generations while contributing to global efforts to preserve biodiversity and ensure food security.