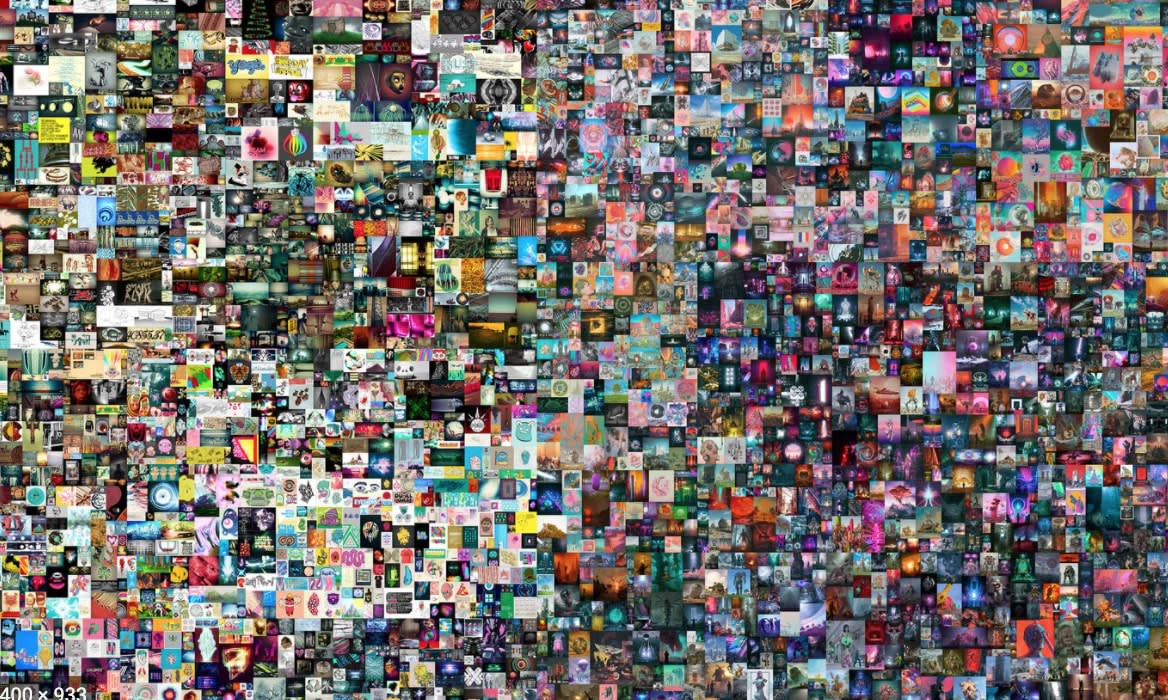

In March, an NFT attached to digital artwork by a graphic artist known as Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann) was sold at auction for US$69.3 million. It became the 100th-most-expensive work of art ever to be officially traded, and is in the top three of auction prices for a living artist.

What is an NFT?

NFT stands for non-fungible token.

“They’re colloquially known as ‘Nifties’,” says artist and researcher Jon McCormack. NFTs are traded using blockchain technology – the same technology that supports cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

But where currencies are “fungible” – that is, mutually interchangeable, so that one Bitcoin has the same value as another – an NFT has value because it’s (supposedly) unique.

The paradox here is that an NFT is a digital asset and therefore not unique. Digital technology allows a song, or a photograph, or a drawing, to be replicated easily and exactly.

Traders and artists are aware of the absurdity – a sense of irony is partly what’s driving the market, Professor McCormack believes. Beeple rode the wave.

“He started experimenting with 3D software, and to learn the system, he made a promise to himself to do one image a day, and he was posting them on Instagram,” Professor McCormack explains. Anyone can now download a copy of the auctioned artwork, Everydays: The First 5000 Days, a composite of these Instagram posts.

“I've got a copy on my hard drive,” Professor McCormack says. “It doesn’t seem like a good deal to me.”

So what are you paying for?

A unique code is attached to the JPEG of the digital artwork – this code or token is the NFT.

“In the art world, it’s very common to have a certificate of authenticity,” Professor McCormack says. “This is a digital version.”

Blockchain technology is often described as a digital ledger, where anyone can see who owns the asset, and how it’s traded. The “crypto” aspect is designed to make the blockchain hacker-proof – but the complexity of the system has an environmental cost (of which more later).

“The problem with NFTs is that the only thing that’s rare is the NFT itself,” Professor McCormack says. “And in some cases, because the technology is still developing, the actual thing that you’ve bought is not contained within the NFT. There’s just a pointer to a webpage. So if that web server goes down or the image gets deleted or disappears, you have nothing, really.

“You still own the NFT, but it’s useless.”

How do you pay for an NFT?

NFTs in their present form were developed by a cryptocurrency called Ethereum, but many other cryptocurrencies now trade their own NFTs, Professor McCormack says.

In October 2017, Ethereum made changes to blockchain technology that enabled players to use NFTs to adopt, breed and trade digital cats in a game called CryptoKitties. A craze took hold, a speculator made the news by selling a Cryptokitty for more than $100,000, and NFTs began to be used in other blockchain games.

(NFTs are now also used as a trading chip between gamers, so that a magical sword in one game, say, can be exchanged for a token with special properties in another game. They must be purchased with a cryptocurrency, and if the currency increases in value, so does the NFT.)

The potential for NFTs to be used as a way of trading in other digital assets that might have value to collectors began to take hold.

So what’s being traded?

Memes are being traded. Basketball stars are selling clips of their best shots. Bands are selling their albums as NFTs. New York Times reporter Kevin Roose wrote a column about NFTs, then created an NFT of the piece and auctioned it to see what would happen. He sold it for US$560,000.

In March of this year, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey sold his first tweet – “just setting up my twttr” – for US$2.6 million.

Virtual shoe brand RTFKT Studios sold its range of digital sneakers in seven minutes for US$3.1 million. And a black virtual hoodie from the streetwear label Overpriced has been purchased for US$26,000 – it can be worn at digital meetings.

Read more: Entertainment v culture: The implications of AI recommendation and generation

Melbourne street artist Lushsux is selling JPEGs of his large mural portraits as NFTs. He said in a recent interview: “I sold a piece called The 8 for 88.8 ETH, or, like, $250,000. I’m literally one of Australia’s highest-paid living artists. Top 20, at least. And some guy is trying to sell one of my Elon Musk portraits for $1.4 million. You could buy a Whiteley for that price. Or, like, a two-bedroom house in Melbourne.”

Lushsux also said he didn’t believe the market would be sustainable for long.

Will the bubble burst?

“One of the interesting differences between Bitcoin and Ethereum is that Bitcoin has a fixed number of coins that are ever going to be available,” Professor McCormack says.

The limited number of Bitcoin adds to their value, “whereas Ethereum is open-ended so that you can keep creating Ethereum”, he says. “So the only thing that’s really valuing Ethereum are the people who’ve invested in it. The only way it gains value is because people just say it’s worth more, and they’re willing to pay for that.”

If the market decides Ethereum is worthless, then the party’s over. Cryptocurrencies were created in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis to avoid being manipulated by governments and central banks. That also makes them vulnerable, because they lack legal and institutional protection.

Professor McCormack believes the NFT trend is partly driven by celebrity culture and its own hype. COVID lockdowns have also played a part.

“People are sitting in front of their screens all day long, and you can own stuff just by doing a transaction on your laptop,” he says. “But if you look at it more deeply, what are you owning, and what’s the concept of ownership?”

What the purchaser of an NFT actually owns remains “a legal grey area”, he says.

“There’s currently no legal framework for what ownership means in NFT terms, as far as I know in any country, unless there’s some explicit agreement as part of the NFT sale – that there’s a transfer of copyright, for example. And because anyone can access that image, it’s hard to see why it’s of such high value.”

NFTs are a mixed bag for artists

If an artist sells their NFT through a sales site – such as Rarible, Foundation or SuperRare – using Ethereum for the recommended minimum price of $100, they can actually lose money because of the high cost of selling art on the blockchain, Professor McCormack says. Ethereum trades consume considerable energy, and from an environmental perspective that’s reason enough to stay away, in his opinion.

“You can own stuff just by doing a transaction on your laptop,” he says. “But if you look at it more deeply, what are you owning, and what’s the concept of ownership?”

On the other hand, artists do have the ability to keep making profits from their work of art if it gains in value down the track.

That’s because some NFTs can specify that the artist receives a cut of the profit whenever the NFT is traded. That’s different from a traditional artwork that can be sold cheaply when the artist is unknown, and then resold at a massive profit without the artist earning extra. (Some jurisdictions have passed laws that seek to redress this.)

Professor McCormack says NFTs have also allowed artists to continue making a living from their work during the COVID era, when travel is difficult and lockdowns have kept people away from galleries.

Fraud is still possible

Forgery is a perennial problem for art collectors, and it’s infiltrated the NFT market as well. The lack of legislative controls adds a greater element of risk.

“There’s instances of people paying money for things that don’t exist, or of people creating NFTs of an artist’s work without that artist’s permission and then trading them, and the person getting the money and the artists getting nothing,” Professor McCormack says.

The environmental cost

Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum rely on an energy-hungry system called “proof of work” to verify their transactions. Some cryptocurrencies that specialise in NFT trades use an alternative system called “proof of stake” to appease customers concerned about greenhouse emissions. The pros and cons of various alternatives are described here.

Professor McCormack believes the most ethical and environmentally responsible stance is to step away from the NFT marketplace altogether.

The business of buying and selling NFTs is “using up energy that could be used for other purposes”, he says.

And the energy of verifying the blockchain transaction is only part of it. “It’s the energy of manufacturing the computers.”

Professor McCormack describes NFT speculation as a form of gambling. It’s contributing to a global silicon chip shortage and “really not being used for anything that’s useful for humanity, in my opinion”, he says.

“If you look at the science of what’s happening to our environment, everyone should be worried about what’s happening to the planet. And I think that really means you have to think carefully about where energy is used and the purpose that it’s used for. I think it’s a moral decision.”