You might have heard about Heard Island and the McDonald Islands recently. They hit international headlines when US President Donald Trump announced his so-called “Liberation Day” global tariffs on 2 April.

Included among his sweeping tariff imposition were these remote, UNESCO World Heritage-listed sub-Antarctic islands, despite there being no local human population based there; no tourism, no agriculture, no infrastructure, so no balance of trade.

The Australian-governed external territories, which lie nearly 4000 kilometres southwest of Perth in the southern Indian Ocean, do, however, host a range of wildlife, including elephant seals, penguins and seabirds that rely on the delicate balance of ice and ocean.

Heard Island is significantly larger than the neighbouring McDonald Islands, at about 368 square kilometres, and is dominated by Big Ben, a glacier-clad 2800-metre-high active, and growing, volcano, often shrouded in cloud. It’s also one of the few sub-Antarctic islands with glaciers descending to the sea.

That, however, is changing rapidly. Here, the glaciers – once emblematic of the island's pristine wilderness – are rapidly retreating, offering a stark reminder of the broader climate challenges that transcend national borders and political rhetoric.

Read more: How scientists collect data in the most remote locations on the planet

Recent research by Monash University’s Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) program has provided alarming insights into the extent of the glacier loss on Heard Island.

Led by Dr Levan Tielidze, Professor Andrew Mackintosh, and Dr Weilin Yang, it provides the most detailed mapping of the island’s glaciers to date.

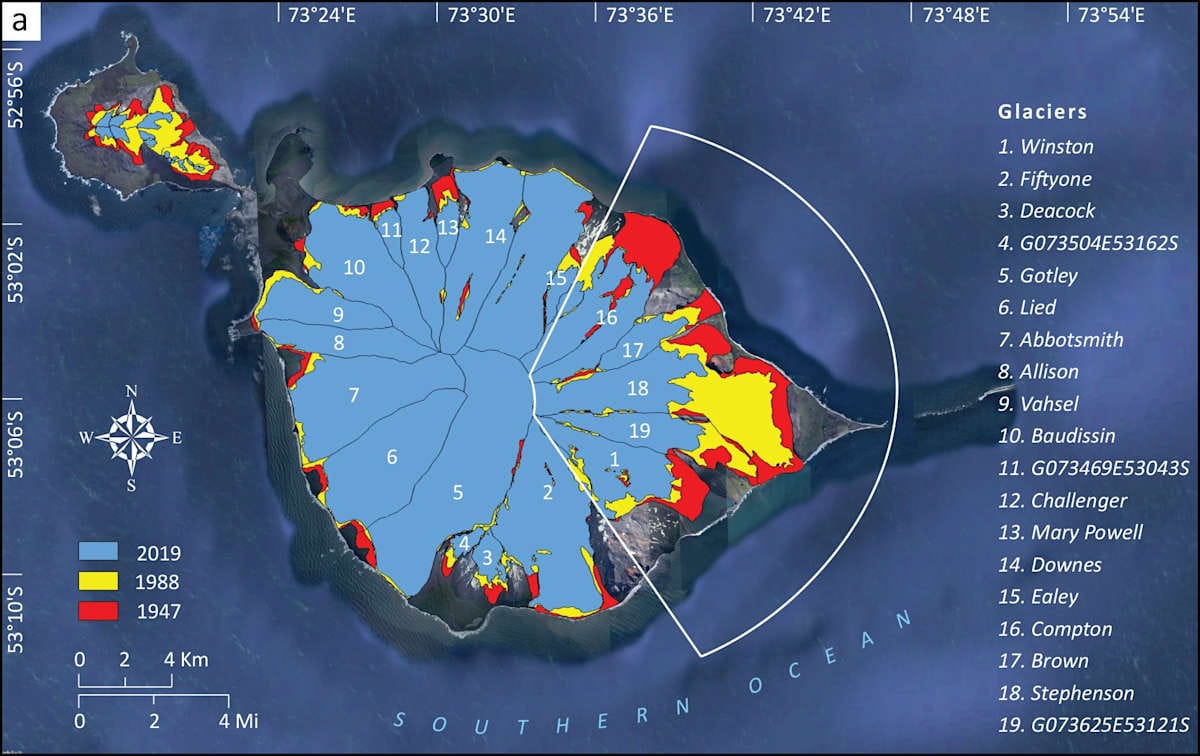

Using topographical maps from 1947 and satellite imagery from historical and current Earth observation platforms, the new research provides a comprehensive glacier inventory of the island, cataloguing 29 glaciers and tracing their outlines in 1947, 1988, and 2019.

Published in academic journal The Cryosphere, the authors found that about 64 square kilometres, or 23.1%, of the icy landscape has been lost since 1947.

Stephenson Glacier on the eastern slope of the island has seen the most dramatic changes, with a retreat of approximately 5.8 kilometres, and the formation of a new lagoon where the glacier once met the sea.

The study also documented a significant rise in surface debris cover and an upward shift in its maximum elevation, due to intensified melting and glacier thinning. These changes are consistent with regional climate data, indicating a warming of 0.7°C over the study period.

“These findings are a bellwether of change for our climate weather systems,” says the study’s lead author, Dr Tielidze.

“While Heard Island is just about as remote as it’s possible to be on Earth, it’s still suffered profound consequences from climate warming, which is almost certainly due to rising greenhouse gas emissions in the 20th and 21st centuries.

“The island’s location in the Southern Ocean is in a key part of the global climate system and an important indicator of the planet’s health, so the changes we are observing paint a really clear and concerning picture.”

Tracking life after the ice

Professor Mackintosh and colleagues were recently awarded an ARC Discovery Project to study how glacier retreat threatens mountain biodiversity, which is poorly understood.

Dr Tielidze also contributed to a recent study, published in Nature, which tracked how ecosystems develop as glaciers retreat.

“Glacier retreat alters freshwater inputs and landscape morphology, affecting the local ecosystems,” Dr Tielidze says.

“For example, glacier retreat exposes new land surfaces, which can be colonised by plants and animals. The new inventory helps track these changes in habitat availability and ecosystem dynamics.”

Read more: Devastatingly low Antarctic sea ice may be the ‘new abnormal’, study warns

Later this year, SAEF researchers plan to join a voyage to the islands aboard the RSV Nuyina as part of the Australian Antarctic Program.

“The team hope to be able to collect some newly-emerging bedrock from areas where the team have mapped this dramatic ice retreat,” Professor Mackintosh says.

“By looking at cosmogenic isotopes in the bedrock, we’ll be able to assess whether the glacier retreat observed in this study is unprecedented across the island’s history.

“Furthermore, by carrying out glacier modelling experiments as part of the Discovery Project, we can investigate what has driven the retreat, including the extent to which humans are responsible.”

Read more: Mapping the glacial melt to predict what lies ahead

As scientists piece together Heard Island’s glacial past and project its glacial and ecological future, they’re helping to illuminate the broader consequences of climate change on glaciers and biodiversity across the globe.

“This mapping shows stark glacier retreat and that further ice loss is unavoidable,” Dr Mackintosh says.

“Whether we retain glaciers, or lose most of them entirely, is up to all of us and the levels of greenhouse gas emission path we choose.

“It might also mean the difference between a future where biodiversity is devastated, and one where the unique life on the island is preserved.

“This tiny, remote island in the middle of the Southern Ocean is a reminder that even the most remote places on Earth are not beyond human impact, or human responsibility.”