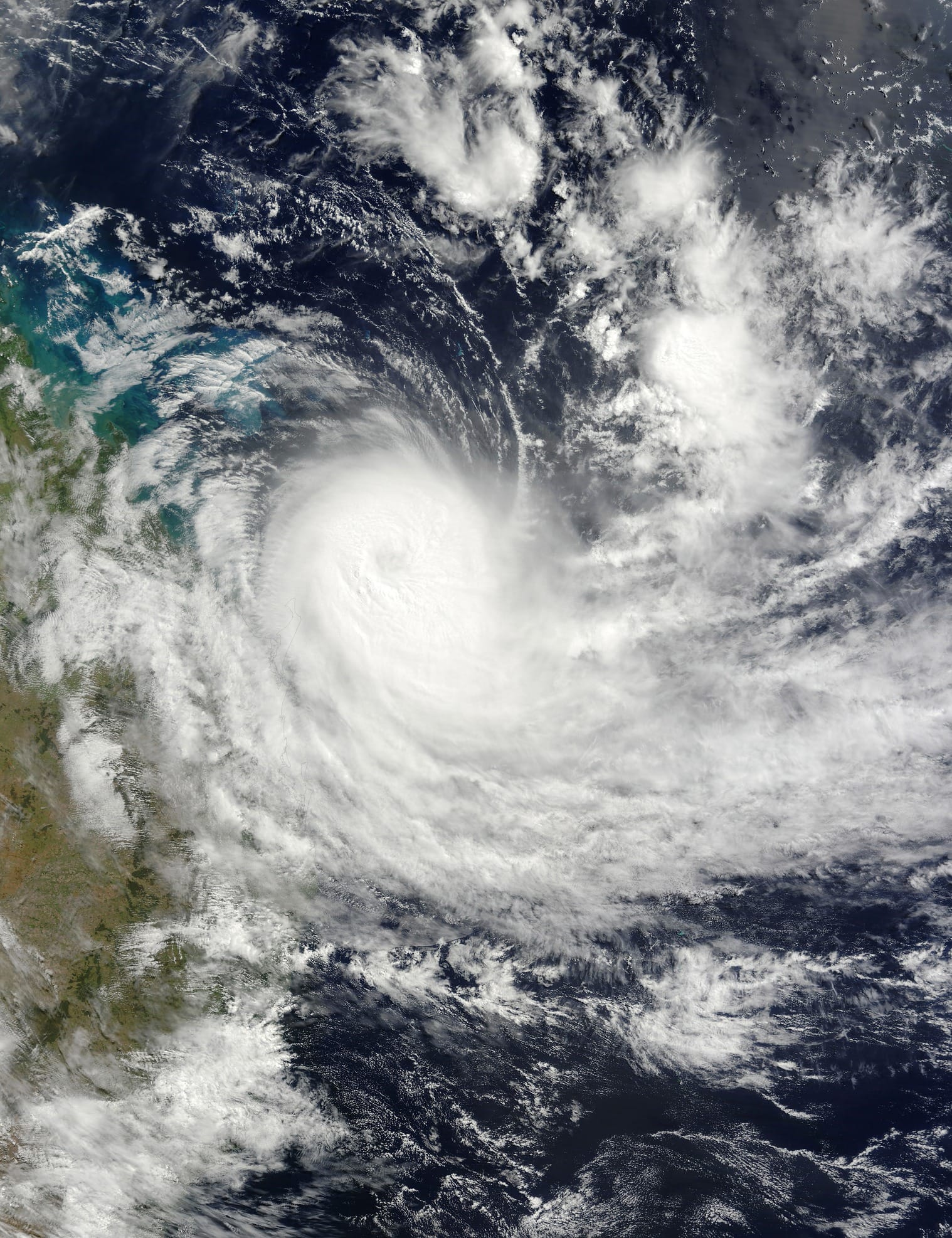

Tropical cyclones are low-pressure weather systems that form over warm tropical oceans. It’s the warmth and moisture of the oceans that gives a tropical cyclone its energy.

They form when an area of low pressure, which meteorologists measure in “hectopascals”, draws in the surrounding warm, moist air, which then rises in deep thunderstorms.

As the air is pulled in towards the centre of low pressure, the Earth’s rotation causes it to spin cyclonically – clockwise in the southern hemisphere and anticlockwise in the northern hemisphere – and it intensifies.

Classification in categories

In the Australian region, tropical cyclones are classified as category one to five depending on the strength of their maximum surface winds.

They are “tropical lows” when their winds are less than 63kmh. When they reach 63kmh they’re classified as a category one tropical cyclone and given a name.

At 89kmh they’re classified as category two, 119kmh category three, 159kmh category four, and more than 198kmh they’re classified as a category five tropical cyclone.

These thresholds are related to the damage that would be expected if a tropical cyclone made landfall with those maximum winds.

However, the spatial extent of damaging winds can extend several hundred kilometres from the eye of the tropical cyclone, which is why the Bureau of Meteorology issues warning graphics showing the extent of damaging winds along with the forecast track.

Further, the intensity of their winds is not correlated with the amount of rain they may produce – a tropical low can still produce heavy rain.

Favourable conditions for a tropical cyclone

Once a tropical cyclone has formed, it will continue to intensify as long as it is over warm oceans of at least 26.5°C and has favourable atmospheric environmental conditions.

Ex-Tropical Cyclone Megan slowly moves over the Northern Territory of Australia, bringing locally intense rainfall and a possibility of damaging wind gusts. pic.twitter.com/nvysRHSXaG— CIRA (@CIRA_CSU) March 19, 2024

These favourable conditions include high humidity, which is conducive to the formation of deep thunderstorms and heavy rain, and is typical of tropical regions, and low levels of atmospheric vertical wind shear.

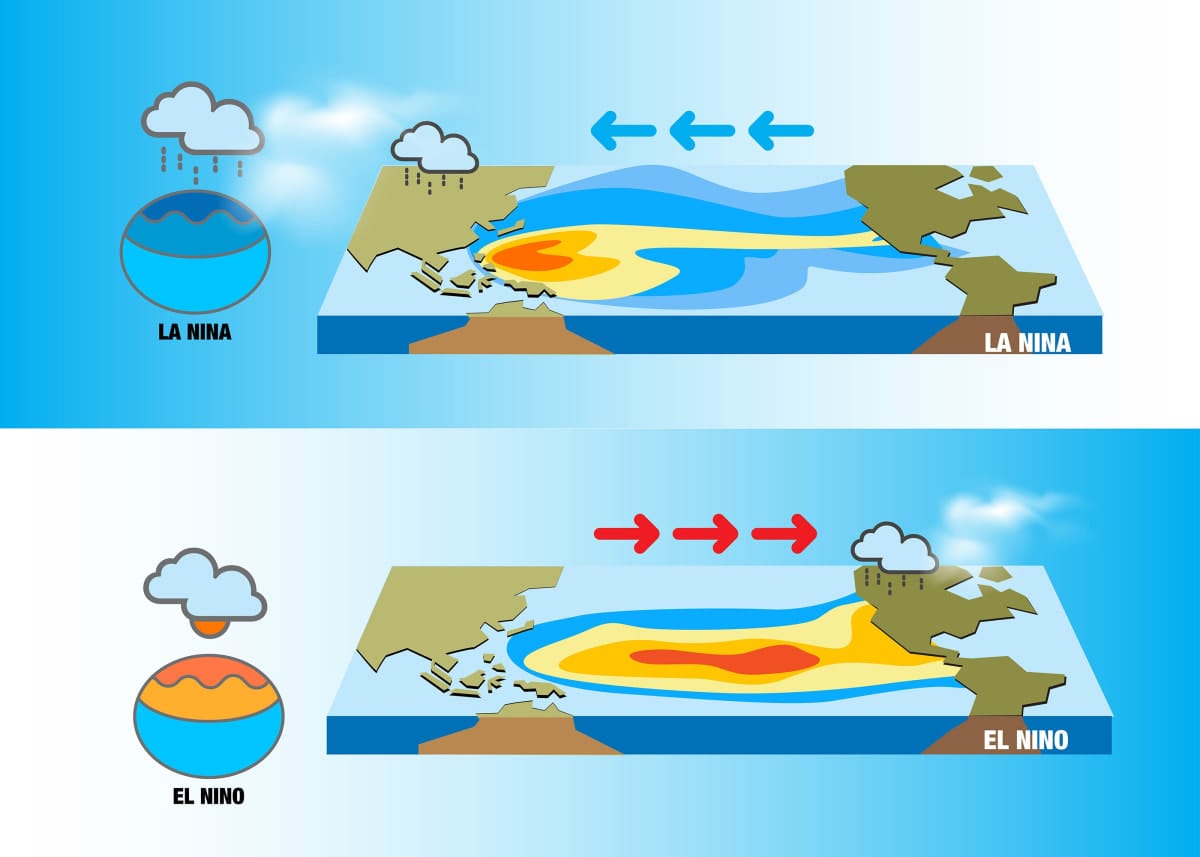

While these environmental conditions can exist for extended periods during the Australian summer, they’re affected by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle.

This is the cycle of Pacific Ocean temperature patterns that oscillates between La Niña, when the ocean waters near the Maritime Continent are warmer than normal, and El Niño, when the ocean waters near the Maritime Continent are colder than normal.

The shifting EL Niño

This season Australia has been under the influence of a strong El Niño. This means that the warm equatorial ocean waters have shifted east away from the Maritime Continent and towards the central Pacific Ocean.

This pattern typically shifts favourable environmental atmospheric patterns and associated tropical cyclone activity slightly away from the Australian east coast toward the dateline.

It doesn’t affect the pattern of tropical cyclone formation of western Australia. However, there’s variability in the ocean water patterns associated with El Niño and how atmospheric patterns in turn respond to the ocean patterns, and the resulting statistical differences in tropical cyclone activity around Australia between different parts of the ENSO cycle are small.

This season, despite the shift of warmer ocean temperatures toward the central Pacific, ocean temperatures were 1-2°C warmer than normal during December to February, and atmospheric moisture was higher than normal just off the east coast of Australia.

In contrast, ocean temperatures were neutral or cooler than normal and the atmosphere was relatively dry off the coast of Western Australia.

This season

To date, there have been nine tropical systems that have formed in the Australian region, four tropical lows, and five tropical cyclones, four of which became severe (category three or higher).

Two of these systems, tropical cyclones Jasper and Kirrily, formed off the east coast of Australia and made landfall in Queensland – Jasper in December, and Kirrily in January.

To put this in context, during the past 20 years, an average 0.8 tropical cyclones form, and 0.3 make landfall on the east coast by the end of January. In contrast, an average three tropical cyclones form off Western Australia, of which 0.8 make landfall by the end of January. Thus, Queensland in particular has had more activity than normal, and Western Australia has been particularly quiet.

Another factor has been the large amount of rainfall associated with these landfalling tropical cyclones.

There are three main factors that can control the amount of rain that occurs in tropical cyclones:

- The amount of environmental moisture, which must be converted into rainfall via physical processes.

- The speed of the tropical cyclone. The slower the tropical cyclone (or remnant low) speed of motion, the longer rain falls in a particular geographic location.

- The longevity of the tropical cyclone remnant once it moves over land.

The current situation

Severe Tropical #CycloneMegan has made landfall. TC Megan crossed the coast at 3:30pm ACST southeast of Port McArthur and is forecast to slowly move inland overnight and weaken below cyclone intensity during Tuesday.

Latest: https://t.co/7OWP3G45MV pic.twitter.com/Zqk0xM3pSY— Bureau of Meteorology, Australia (@BOM_au) March 18, 2024

Right now, severe tropical cyclone Megan is continuing to have an impact on the southwestern Gulf of Carpentaria coast in Arnhem Land, bringing heavy rain, strong winds and heavy seas to coastal regions that experienced tropical cyclone Lincoln in the middle of February.

As the fourth tropical cyclone to make landfall east of Darwin this season, the question we could be asking of this season is: Where are all the Western Australian tropical cyclones?