You only get 52 teeth in your lifetime – 20 baby teeth, followed by 32 adult teeth.

It’s not like that for all animals. Some, like rodents, never replace their teeth. Others, like sharks, keep replacing them again and again.

Read more: Yes, baby teeth fall out. But they're still important – here's how to help your kids look after them

So why do we humans replace our teeth only once? And how does the whole tooth replacement process work?

These are tricky questions, and we don’t have all the answers. But a new discovery about the strange tooth-replacement habits of the tammar wallaby, a small Australian marsupial, may help shed some light on this dental mystery.

Not everybody replaces teeth the same way

It’s been long assumed modern mammals all replace their teeth the same way. However, advances in 3D scanning and modelling have revealed mammals with unusual tooth replacement, such as the tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii) and the fruit bat (Eidolon helvum).

These mammals have given us important clues as to how humans and other mammals have evolved from ancestors with continuous tooth replacement.

How do humans make and replace teeth?

Human teeth begin growing between the sixth and eighth week of an embryo’s development, when a band of tissue within the gums called the primary dental lamina starts to thicken. Along this band, clusters of special stem cells appear at the sites of future teeth, known as “placodes”.

The placodes then begin to grow into teeth, going through the bud, cap and bell stages along the way. They form into their final shape, and harden with layers of dentine and enamel.

Eventually, they’ll erupt through the gums. The incisors are the first to erupt, as early as six months old, which is why it’s called the teething phase.

This generation of teeth, which grow from the primary dental lamina, are known as “primary dentition”, or baby teeth.

Secondary, or adult, teeth grow a little bit differently. An offshoot of tissue called the successional lamina grows out from the baby tooth, and that tissue develops the replacement tooth like an apple on a branch of a tree. Adult teeth begin to grow before we’re born, but take many years for the full set to form and eventually appear.

Replacement occurs when the adult teeth get large enough that they finally push out the baby teeth, and remain as the permanent set of teeth for the rest of our lives. The first molar usually erupts between six and seven years of age, while our wisdom teeth are the last to appear (roughly between 17 and 21 years of age).

Most mammals replace their teeth once in the course of their lives, like we do. This is known as “diphyodonty” (two sets of teeth).

Some groups of mammals, such as rodents, don’t replace their teeth at all. These “monophyodonts” get by with the same set of teeth for their whole lives. There are also a few unusual mammals, such as echidnas, that don’t grow any teeth at all.

Learning from the wallaby

The tammar wallaby is also a diphyodont, replacing its teeth only once.

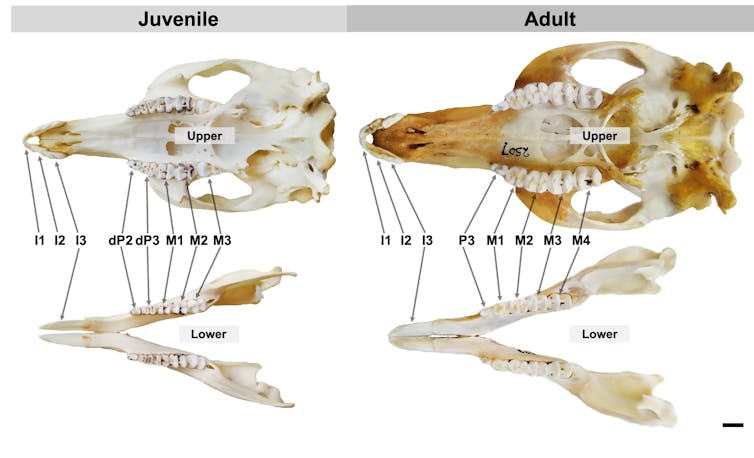

Scientists long assumed it replaced its teeth in the same way humans do, though historical notes going back as far as 1893 noticed unusual things about this marsupial’s tooth development. For starters, while we replace our incisors, canines and premolars, tammar wallabies only replace their premolars.

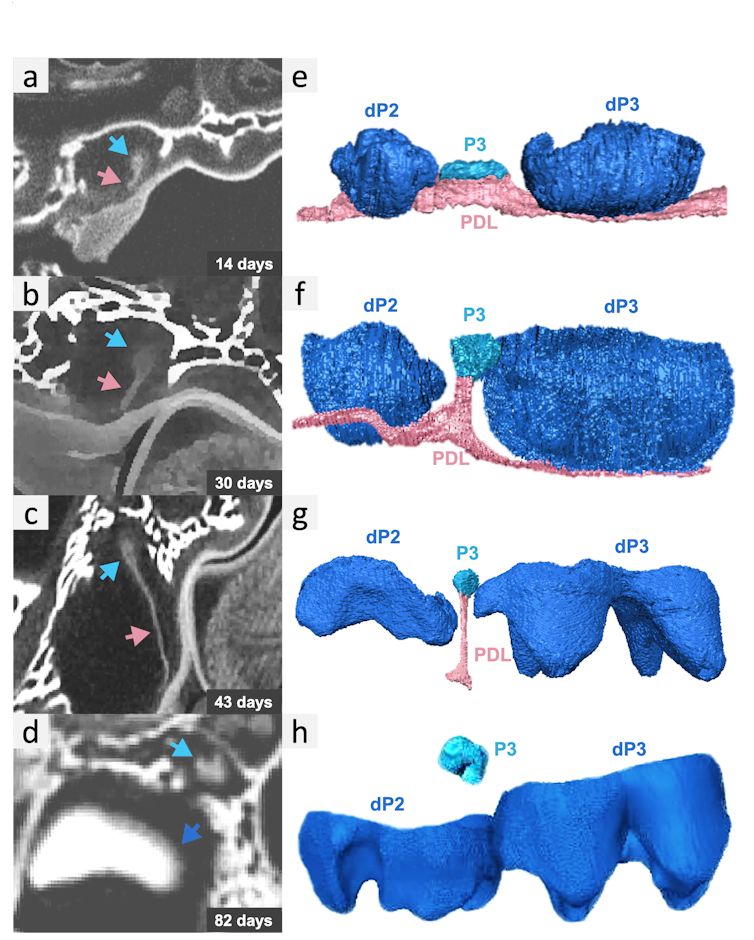

Recently, my colleagues at Monash University and the University of Melbourne and I observed the teeth of tammar wallabies from the embryo through to adulthood. We used a technique called diceCT, which combines staining and CT scanning, and found something surprising.

Instead of replacement premolar teeth developing from the successional lamina, they were in fact delayed baby teeth developing from the primary dental lamina.

This means the tammar wallaby does not have any traditional tooth replacement. This discovery opens up a huge set of new questions. What exactly are these teeth?

One explanation for these delayed baby teeth could be a link to our ancestry of continuous tooth replacement.

Your teeth are millions of years in the making

Unlike mammals, most other animals, including fish, sharks, amphibians and reptiles, replace their teeth multiple times (they are “polyphyodonts”). Mammals lost this ability about 205 million years ago.

The reason we stop making teeth is because our dental lamina degrades after our second set is made, while it remains active in polyphyodonts.

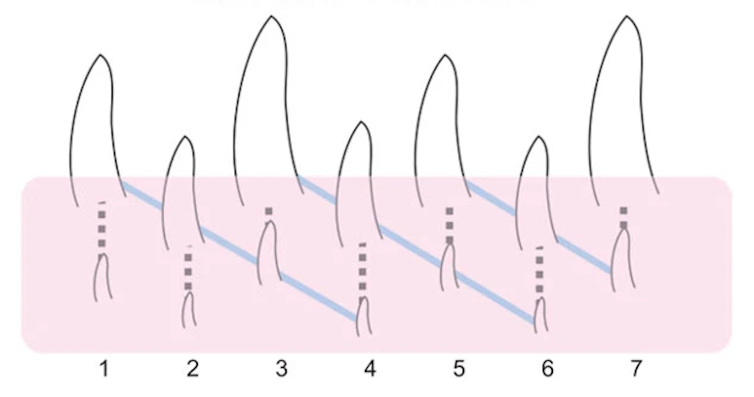

Interestingly, in modern and fossil polyphyodonts, the replacement teeth often develop in groups of alternating waves, known as “Zahnreihen”.

While the tammar only replaces its premolars, these delayed baby teeth could represent the presence of the Zahnreihen still occurring in modern mammals.

This gives us a clue about how we’ve evolved from ancestors with continuous tooth replacement – by modifying and reducing a system that’s hundreds of millions of years old.

Research has also found that fruit bats (Eidolon helvum) make replacement teeth in unusual ways, including growing them in front of the baby tooth, behind it, beside it, or splitting off from it.

This is exciting because, together with the tammar, it shows there may well be a wealth of tooth replacement diversity across mammals happening right under our noses – or our gums.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.