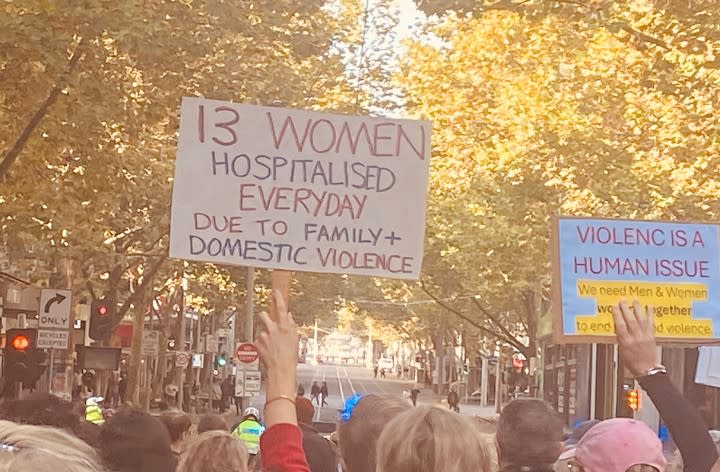

In the wake of numerous killings of women allegedly by men’s violence in 2024, thousands of Australians have joined rallies across the country to demand action and better responses to all forms of domestic, family and sexual violence.

Some have called for a perpetrator register or a domestic violence disclosure scheme – a resource people can check to find out if a particular person has a documented history of domestic violence. This history could include things such as prior convictions, intervention order histories, and other non-domestic violence-related offending such as property offences.

In Australia, only South Australia has a domestic violence disclosure scheme. New South Wales piloted a scheme in 2016, but it was discontinued in 2018. No other state or territory has introduced a scheme, but several have considered the idea.

So, how well do these schemes work to improve safety for women? To find out, we interviewed scheme users, specialist service providers, legal practitioners, academics, and policymakers in Australia and New Zealand.

Our new research, funded by the Australian Research Council and published today by Monash University and the University of Liverpool, found they may not improve safety for victim-survivors.

What is a domestic violence disclosure scheme

In Australia, domestic violence disclosure schemes (such as the one operating now in South Australia and the one piloted then discontinued in NSW) have broadly had three objectives:

- To strengthen the ability of the police and specialist service providers to provide appropriate protection and support to victims at risk of domestic violence

- To reduce incidents of domestic violence through prevention of future harm

- To empower people to make informed choices about their safety in their relationships.

Each of the schemes is administered differently. In some cases, applicants can lodge an application online. In others, an applicant must lodge their application directly with the police.

Confirming existing suspicions

We interviewed 11 people who had used a domestic violence disclosure scheme. With the exception of two, each had already separated from the person they were seeking information about.

Each person had experienced some form of abuse before separating and before accessing the scheme. Several also held suspicions about their partner’s abusive behaviours in prior relationships.

All applicants interviewed, except one, got information about their partner’s history from the domestic violence disclosure scheme. In one case, the applicant’s request was denied. She was not told why.

Today we have released our report examining the merits & limits of domestic violence disclosure schemes in Australia & NZ.

Our research suggests domestic violence disclosure schemes may not improve safety for victim-survivors of intimate partner violence. Grateful to the scheme… pic.twitter.com/kr80AyphMt— Kate Fitz-Gibbon (@Kate_FitzGibbon) May 2, 2024

Many applicants said the information they received didn’t come as a surprise, but rather confirmed suspicions they already held about their partner’s history of abuse.

In other words, most applicants interviewed in this project used the scheme after they had already left the relationship and had experienced abuse.

This signals the scheme is working different to intended – not as a scheme to prevent violence from occurring in the first place, but rather as a scheme that confirms decisions made to separate from an abuser after violence has already occurred.

Timely information is key

For information-sharing to be effective, it must be timely. But our interviewees reported wildly different experiences in this regard; the time between making the application and receiving the disclosure ranged between one week and three months.

An evaluation of the since-disbanded NSW pilot scheme reported similar “clunky” and time-consuming data-sharing issues.

Do we have the reliable data needed to support this scheme?

Domestic violence disclosure schemes rely on the collection and sharing of reliable data about perpetrators’ histories.

But a vast amount of domestic, family and sexual violence in Australia goes under-reported. Histories of violence documented by police may fail to capture a full picture of the risk an individual poses to their intimate partner.

If a woman contacts a domestic disclosure scheme about her partner or ex and learns they have no record of them having a violent past, this could create a false sense of security for her, potentially raising the risk level.

Effective information-sharing means national information-sharing. But under the NSW pilot scheme, for example, offences occurring in other states and territories were not shared with the person contacting the domestic violence disclosure scheme. A state-based scheme risks lulling applicants into a false sense of security when their partner’s history of violence in another state is not visible in the state they currently reside in.

Enhancing access to supports

Advocates of domestic violence disclosure schemes often position it as an additional pathway to services and safety planning for victim-survivors. It’s framed as an early intervention scheme that connects victim-survivors with support services, including safety planning, risk assessment and management, and counselling.

Numerous applicants in our study didn’t receive follow-up support of this kind. Sharing information with no follow-up supports and safety planning may put the applicant at greater risk of harm.

Failing to provide follow-up support represents a missed opportunity to enhance the safety of victim-survivors and offer crucial supports to an individual who has sought help.

We need to fund what actually works

Australian states and territories – in partnership with the federal government – are moving ahead with the delivery of the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032. There’s a critical need to scrutinise not only what works, but what doesn’t work well.

Domestic violence disclosure schemes are expensive, thanks to the cost of the administrative workload, data-sharing, training, and provision of follow-up support services.

Our research suggests domestic violence disclosure schemes may not improve safety for victim-survivors of intimate partner violence. Given the scale of the crisis we face, our research suggests the resources required to run them may be better spent elsewhere.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation, and was co-authored with Ellen Reeves, a lecturer in criminology at the University of Liverpool.