The safest place for your baby to sleep is in their own cot in the same room as their parents or adult caregivers. Sound scientific evidence tells us babies should always be placed to sleep on their back, never on their side or stomach.

But what if your baby rolls on to her stomach in her sleep? Should you turn her back over? If she can roll back over by herself then there’s no need, but if she can’t then you should turn her on to her back.

Why is back sleeping so important?

Baby deaths attributed to sudden unexpected death in infancy (referring to all cases of sudden and unexpected death in infancy including sudden infant death syndrome and fatal sleeping accidents) have fallen by 80% since the introduction of safe sleeping campaigns in the 90s. It’s estimated 9,500 infant lives have been saved in Australia alone.

There’s now conclusive evidence from many countries that sleeping babies on their tummies (prone sleeping) significantly increases the risk of sudden unexpected death. Studies have also identified the side sleeping position as unstable, and many infants are found on their tummies after being placed to sleep on their side. Babies who have been born preterm are at increased risk of sudden death.

The position we sleep in dictates how easily and how often we’ll be woken up during sleep. Arousal from sleep is a physiological protective mechanism that is widely believed to be deficient in infants who succumb to sudden and unexpected death.

When we fall asleep, blood pressure, heart rate and breathing slow, and there can be pauses in breathing (apnoeas). Brief arousals from sleep increase blood pressure, heart rate and breathing rate.

Studies in babies have shown placing a baby on their tummy not only makes them much more difficult to rouse from sleep, but also lowers blood pressure and the amount of oxygen available to the brain. Parents sometimes place their baby on their stomach as they “sleep better this way”. This is because they don’t wake up as frequently in this position.

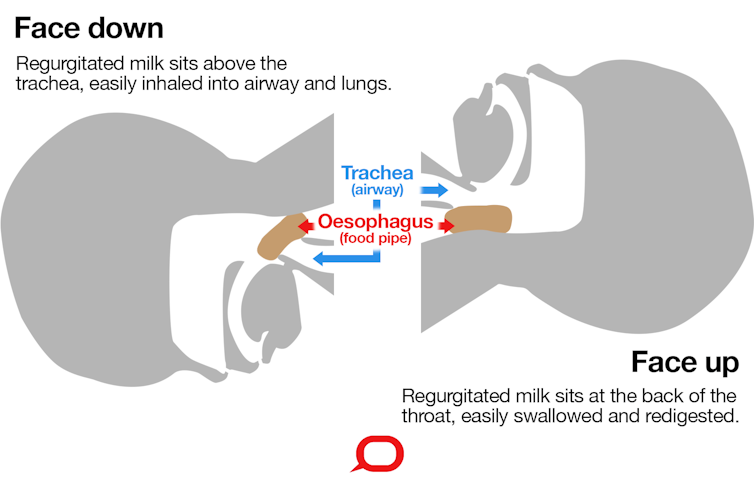

Some parents are concerned sleeping their baby on their back will increase the risk of choking. But careful study of the baby airway has shown babies placed to sleep on their backs are less likely to choke on vomit than when on their stomach.

When on the back, the upper respiratory airway is above the oesophagus (digestive tract). So regurgitated milk ascending the oesophagus is readily swallowed again and doesn’t go down the respiratory tract. When the baby is placed on the tummy the oesophagus sits above the baby’s upper airway. If the baby regurgitates or vomits milk, it’s relatively easy for the milk or fluid to be inhaled into the airway and lungs.

What if my baby rolls over in her sleep?

Babies start to learn to roll over from back to front as early as four months. It may take her until she’s about five or six months to be able to roll from tummy to the back, because she needs stronger neck and arm muscles to accomplish this.

Babies should always be put down to sleep on their back. But once your baby can roll from back to front and back again on their own confidently, they can be left to find the position they prefer to sleep in (this is usually around five to six months). If babies cannot yet roll from front to back, then they should be turned onto their backs if parents find them asleep on their tummies.

Devices such as wedges and positioners, which are promoted as keeping babies from rolling over, should never be used, as they can be a suffocation hazard. There should be nothing in the cot but your baby and any safe bedding to keep her warm.

An important note on wrapping or swaddling

If you wrap or swaddle your baby for sleep, this needs to be adjusted for the age of your baby. Babies under two or three months may have their arms included in the wrap to reduce the effects of the Moro or “startle” reflex, where the baby feels unsupported and as though they’re falling.

Babies older than three months can have their lower body wrapped but with their arms free. This allows the baby access to their hands and fingers, which promotes self-soothing behaviour while still reducing the risk of the baby turning onto the tummy.

The startle reflex should have disappeared by the time the baby is four to five months, so there’s less need for wrapping. Wrapping and swaddling should be discontinued as soon as the baby shows the first signs of rolling over. Wrapped or swaddled babies should NEVER be placed on their tummy to sleep.

A wide range of infant care products designed as infant swaddles, wraps and wearable blankets have proliferated on the market. There’s very limited evidence these promote infant settling, keep babies on their back and no evidence these products reduce the risk of sudden death.

But there is some evidence a properly fitting infant sleeping bag – one with a fitted neck and armholes that’s the right size for the baby’s weight – may be protective against sudden death. This is possibly because they delay the baby rolling onto their tummy and eliminate the need for bedding in the cot.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.