Early this month, former Telstra boss David Thodey released a draft review of the NSW revenue system as it relates to federal funding. The review was commissioned by the NSW Treasurer, and the centrepiece of its recommendations was an increase in the GST.

The rationale is clear: It's far easier to raise the GST than undertake politically-difficult reforms to corporate taxation and incentives targeting renewable industries and R&D.

Former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull devoted considerable time to a lower corporate tax regime, arguing Australia’s company tax was internationally uncompetitive. He was right – tax competition is a global sport. The winners reap rivers of gold. The losers – you and I – merely pay more tax.

Read more: Australia needs a GST holiday

If Amazon shares hit US$5000, CEO Jeff Bezos becomes the world’s eighth-largest economy. And he owes it all to you. Because Amazon pays very little tax. Veteran investor Warren Buffet knew the tax code was slanted against income taxes versus capital gains when he discovered his secretary paid more tax than he did, leading to the "Buffet rule" – upper and high-income earners should not pay less tax than lower-income workers.

That hasn't happened. Instead, corporations stash revenues in off-balance-sheet special purpose entities (SPEs), by using special tax jurisdictions and trusts located in the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Ireland, among others.

In 2016, the EU Commission ordered Apple that pay €13 billion ($A19.2 billion) in taxes to Ireland on the basis that the EU arm of the company, headquartered in Ireland, had received "state aid" (that is, untaxed benefits), which is unlawful in the EU single market. Apple appealed the decision in 2019. I asked some G20 sherpas’ staff about SPE reform during the 2014 Brisbane G20 summit; they refused to even discuss it.

The Bush administration introduced a tax holiday for US firms in 2004, allowing multinational corporations to repatriate overseas earnings, but the scheme was abruptly abandoned once it was realised it raised little federal revenue. The Trump administration also bowed to the pressure of a corporate tax holiday, permitting Apple, Google and Amazon, among many others, to repatriate more than US$1 trillion held in foreign jurisdictions and SPEs. Nevertheless, the Trump tax repatriation still fell well short of the US$4 trillion the administration predicted.

... the GST is a lazy, regressive, blunt instrument that operates as a substitute for taxation reform across the spectrum, instead of reforming vested interests targeting financial and property speculation, as well as resources profits.

What did US corporations do with this windfall? In many cases, they undertook share buybacks, which boosted their stock prices, thus further enriching both investors and corporate executives with stock options. This does little to repair fiscal imbalances.

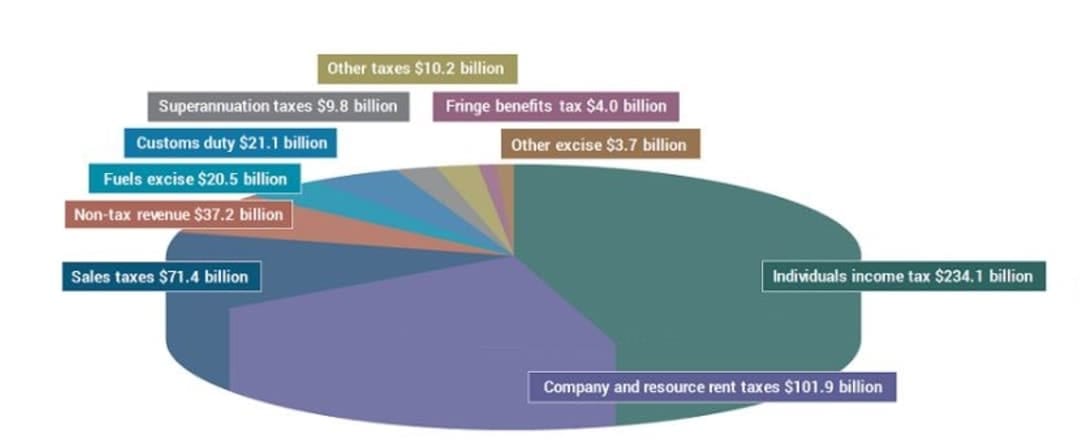

The bottom line is that there are only three ways to raise taxes: income, corporate and indirect. Corporations pay the least by far, and few governments have made serious inroads into increasing corporate contributions to the taxation base. Indeed, under Trump, business tax repatriation is a retrograde step, while Trump’s tax cuts have also eroded the US fiscal base.

Despite myriad promises during successive G20 summits, one-third of Australian corporations pay zero tax. But at least we have stopped giving drug dealers a tax deduction.

A tax regime for a post-COVID economy

Globally, slow or low growth in the post-COVID economy will result in cuts in government services and subsidies as taxation revenues decline. In the absence of stable economic growth, governments will be compelled to either print money, go further into debt, or raise taxes to maintain services provision.

The first two options are not long-term revenue strategies. Consequently, governments will rely on taxation to repair the fiscal damage wrought by the pandemic. As ABS data shows, Australian tax per capita has increased every year since the 2008 GFC, rising 4.4 per cent overall in 2018-19.

GST is frequently regarded as a regressive tax. It places considerable imposts upon low-income-earners, who are given little compensation and save little of their income; thus, virtually all their expenditures are taxed. For higher-income classes, the GST isn't a barrier to consumption, whereas a 10% tax added to replacing a house roof or to dental work represents a considerable financial burden. But even if Australia introduced a universal basic income (UBI), governments would immediately claw back at least 10% in consumption taxes.

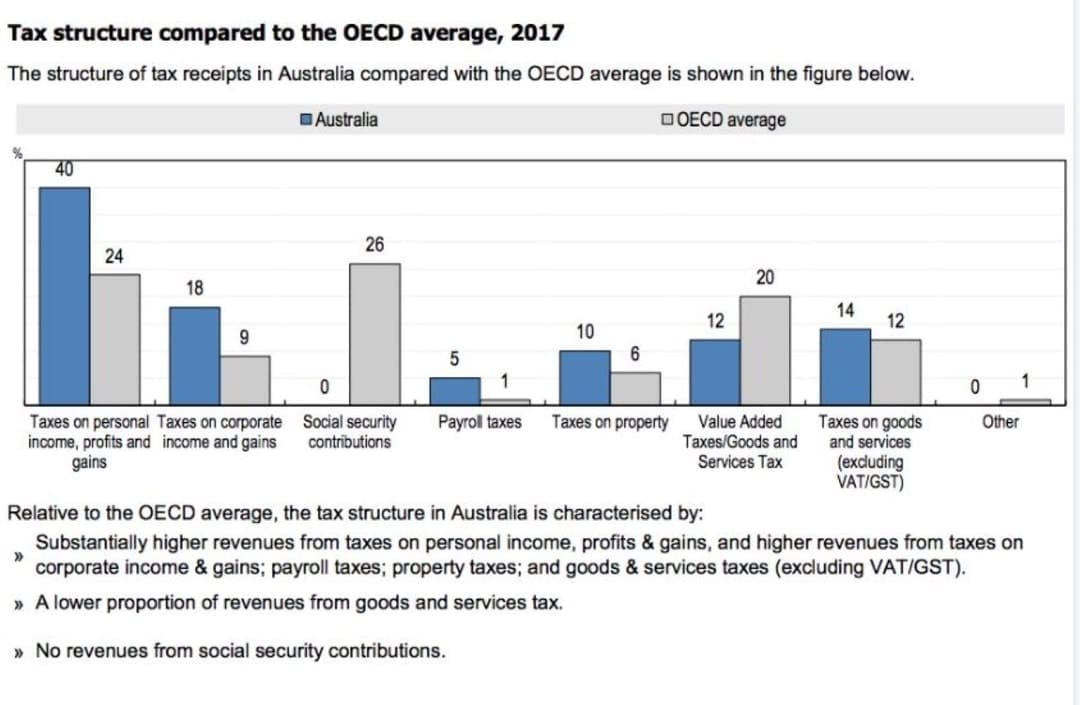

Australia has high income taxes compared to the OECD average, but a relatively low GST rate. However, indirect taxes, excluding GST, exceed those of comparable countries on average (below).

The rent-seekers cometh

The NSW Treasurer’s campaign to increase the GST is backed by a carefully-orchestrated PR campaign to soften the voters. Inevitably, this brought the usual suspects out of the wood – rent-seekers.

Unsurprisingly, business campaigns for GST increases because it doesn’t pay for it; the consumer does. More to the point, this takes the heat off corporate taxation as well.

States campaign for GST increases because indirect taxes give them a bigger share of the national tax cake. Moreover, the political damage associated with GST rate increases are borne predominantly by federal governments. The author of the 2008 tax review, former treasury secretary Ken Henry, also supports a higher GST rate.

GST increases are a distraction from the main game – corporate and resources taxes.

My argument is that the GST is a lazy, regressive, blunt instrument that operates as a substitute for taxation reform across the spectrum, instead of reforming vested interests targeting financial and property speculation, as well as resources profits. The GST base could be expanded to hit, say, basic food or private school education, or this list. GST hikes allow governments to eschew carefully-targeted tax incentives directed at future key employment sectors, such as green jobs, carbon pricing, digital economy, and manufacturing and innovation R&D.

Here's what we should be doing:

1. Tax the digital economy

The digital economy has proven notoriously difficult to tax. The rise of the gig economy is also hard to police. Workers may fall below the GST reporting threshold; the informal or "shadow" economy leads to regulatory avoidance, while workers use cash and cryptocurrencies. Unregulated digital services allow international labour to displace domestic workers across borders (I could pay offshore Indian graduates to grade papers – but I don’t). The EU shadow economy is valued at €2.4 trillion ($A3.89 trillion), while the global informal economy is estimated at nearly $US10 trillion – bigger than China’s GDP.

The French government has sought to deal with both corporate tax evasion and the digital economy by imposing a 3% tax on revenues. In 2020, Paris postponed the tax, as Trump threatened tariffs on French exports, due to allegations of harm to the US tech sector. Verdict: It’s complicated.

2. Create sovereign wealth funds

Kevin Rudd tried, and failed, to implement a Resources Super Profits Tax (RSPT). An aggressive campaign waged by the resources industry – 83% foreign-owned – cost Rudd his job. The Gillard government implemented the tepid Mining Resources Rent Tax, which collected virtually no revenue until it was repealed by the Abbott government.

In contrast, the UK introduced a petroleum super profits tax in 1975, until the Cameron-Clegg government abandoned the tax in 2016. For 40 years, North Sea oil revenues funded everything from the NHS to mortgage tax relief. The UK deserves plaudits for reducing VAT to zero under COVID-19 for eBooks and online journals. It also charges no VAT on food, except for junk foods and alcohol.

Sensibly, Norway has locked oil and gas tax revenue into a sovereign wealth fund worth more than US$1 trillion. The Australian state and federal governments should be doing precisely this, with taxes on resources super profits, including iron ore, coal and gas.

3. Financial transactions levy

If you're an investor on the domestic or foreign exchanges, you pay GST to your broker, but you can claim it back as an expense. Your broker pays zero GST on every trade. The ASX already collects a small levy on transactions, but this could easily be extended to a "Tobin tax", as the Australia Institute has argued, without imposing a significant burden on business.

4. Land taxes or stamp duty?

State governments saw the writing on the wall in 2018-19, when property prices slumped, despite a pre-COVID recovery. Inflated real estate prices meant Victoria alone expected state coffers to swell by $6 billion annually. A substitute land tax would require an estimated $4000 impost on every household.

Inevitably, the states will transition to land taxes to avoid the peaks and troughs of real estate booms and busts. Moreover, land taxes guarantee revenue in perpetuity. But the longer the national cabinet delays reforms to the tax revenue base, the longer states will depend upon duties, licensing fees and royalties. Impoverished state revenues from a shrunken GST cake in a recessed post-COVID economy will place further financial pressure on essential services, such as health, social services and education.

As for negative gearing and the capital gains concession, neither major party wants to revisit this, given the ALP’s reforms have twice been rejected in federal elections.

No neutrality

There's no such thing as a neutral tax policy; revenue-neutral tax changes, yes. But in the post-COVID environment, governments will be left with an unpalatable choice between either increasing income taxes, or boosting less conspicuous indirect taxes to fill budget black holes. Governments will inevitably choose the latter, as consumption taxes like GST are less easily understood, apply across the board, and slug everyone from students and pensioners, to tourists and the homeless. Except corporations and sole traders, which merely act as GST tax intermediaries.

Every single country – bar Australia – that has introduced a GST/VAT has increased the rate. Rates rose appreciably after 2008. In 2010, New Zealand raised its GST from 12.5% to 15%. Australia’s GST rate will exceed 10% by 2030, irrespective of the federal government’s protestations to the contrary. With higher unemployment, combined with lower corporate and income tax revenues, indirect tax increases are a mathematical certainty.

The moral? Never stand between a state treasurer and a swag of GST revenue.