In the wake of Donald Trump’s election victory, Meta chief executive Mark Zuckerberg fired the fact-checking team for his company’s social media platforms. At the same time, he reversed Facebook’s turn away from political content.

The decision is widely viewed as placating an incoming president with a known penchant for mangling the truth.

Meta will replace its fact-checkers with the “community notes” model used by X, the platform owned by avid Trump supporter Elon Musk. This model relies on users to add corrections to false or misleading posts.

Musk has described this model as “citizen journalism, where you hear from the people. It’s by the people, for the people.”

"Old school journalism is dead. Citizen journalism is the future. It's by the people, for the people. It absolutely fundamental that the people actually get to decide the news and the narrative."

一 Elon Musk

pic.twitter.com/phwLKgZuKN— DogeDesigner (@cb_doge) December 21, 2024

For such an approach to work, both citizen journalists and their readers need to value good-faith deliberation, accuracy and accountability. But our new research shows social media users may not be the best crowd to source in this regard.

Our research

Working with Essential Media, our team wanted to know what social media users think of common civic values.

After reviewing existing research on social cohesion and political polarisation, and conducting 10 focus groups, we compiled a civic values scale. It aims to measure levels of trust in media institutions and the government, as well as people’s openness to considering perspectives that challenge their own.

We then conducted a large-scale survey of 2046 Australians. We asked people how strongly they believed in a common public interest. We also asked about how important they thought it was for Australians to inform themselves about political issues and for schools to teach civics.

Importantly, we asked them where they got their news – social media, commercial television, commercial radio, newspapers or non-commercial media.

What did we find?

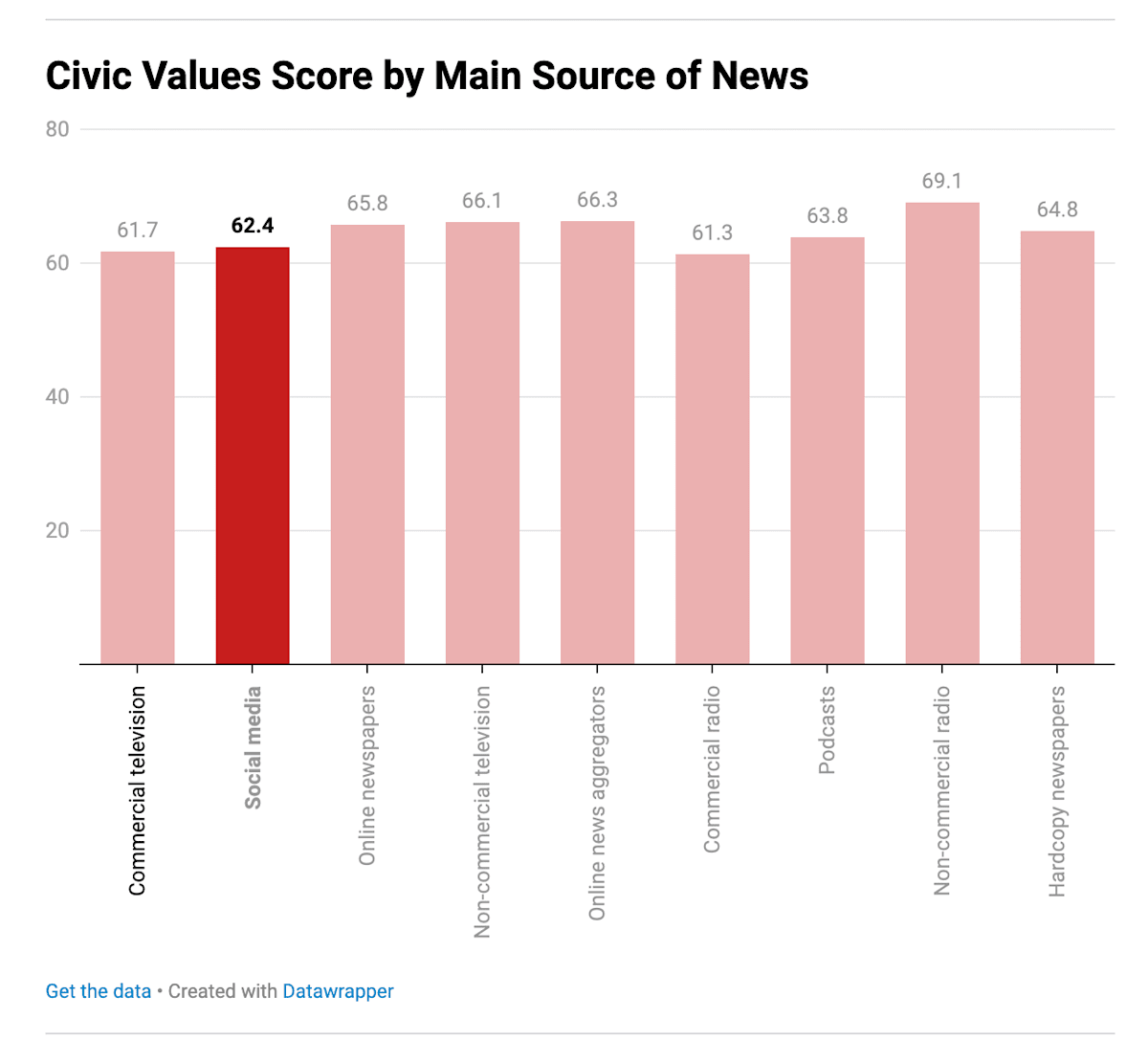

We found people who rely on social media for news score significantly lower on a civic values scale than those who rely on newspapers and non-commercial broadcasters such as the ABC.

By contrast, people who rely on non-commercial radio scored highest on the civic values scale. They scored 11% higher than those who rely mainly on social media, and 12% higher than those who rely on commercial television.

The lowest score was for people who rely primarily on commercial radio.

People who relied on newspapers, online news aggregators, and non-commercial TV all scored significantly higher than those who relied on social media and commercial broadcasting.

The survey also found that as the number of different media sources people use daily increased, so too did their civic values score.

This research does not indicate whether platforms foster lower civic values or simply cater to them.

But it does raise concerns about social media becoming an increasingly important source of political information in democratic societies like Australia.

Why measure values?

The point of the civic values scale we developed is to highlight the fact that the values people bring to news about the world is as important as the news content.

For example, most people in the United States have likely heard about the violence of the attack on the Capitol protesting Trump’s loss in 2020.

That Trump and his supporters can recast this violent riot as “a day of love” is not the result of a lack of information.

It is, rather, a symptom of people’s lack of trust in media and government institutions, and their unwillingness to confront facts that challenge their views.

In other words, it’s not enough to provide people with accurate information. What counts is the mindset they bring to that information.

No place for debate

Critics have long been concerned that social media platforms do not serve democracy well, privileging sensationalism and virality over thoughtful and accurate posts. As the critical theorist Judith Butler put it:

“... the quickness of social media allows for forms of vitriol that do not exactly support thoughtful debate.”

Sociologist Zeynep Tufekci said social media is less about meaningful engagement than bonding with like-minded people and mocking perceived opponents. She notes, “belonging is stronger than facts”.

Her observation is likely familiar to anyone who has tried to engage in a politically charged discussion on social media.

These criticisms are commonplace in discussions of social media, but have not been systematically tested until now.

Social media platforms are not designed to foster democracy. Their business model is based on encouraging people to see themselves as brands competing for attention, rather than as citizens engaged in meaningful deliberation.

This is not a recipe for responsible fact-checking. Or for encouraging users to care much about it.

Platforms want to wash their hands of the fact-checking process, because it’s politically fraught. Their owners claim they want to encourage the free flow of information.

However, their fingers are on the scale. The algorithms they craft play a central role in deciding which forms of expression make it into our feeds and which do not.

It’s disingenuous for them to abdicate responsibility for the content they chose to pump into people’s news feeds, especially when they’ve systematically created a civically challenged media environment.

The author would like to acknowledge Associate Professor Zala Volcic, Research Fellow Isabella Mahoney and Research Assistant Fae Gehren for their work on the research on which this article is based.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.