France’s New Popular Front – a contingent alliance of green and left-wing parties – along with Emmanuel Macron’s diminished centrists pushed the far-right Rassmeblement National into third place in elections to France’s National Assembly.

For now, the prospect of a far-right government in France has been held in check. It is, however, impossible to ignore the rise of the far-right and the radical right.

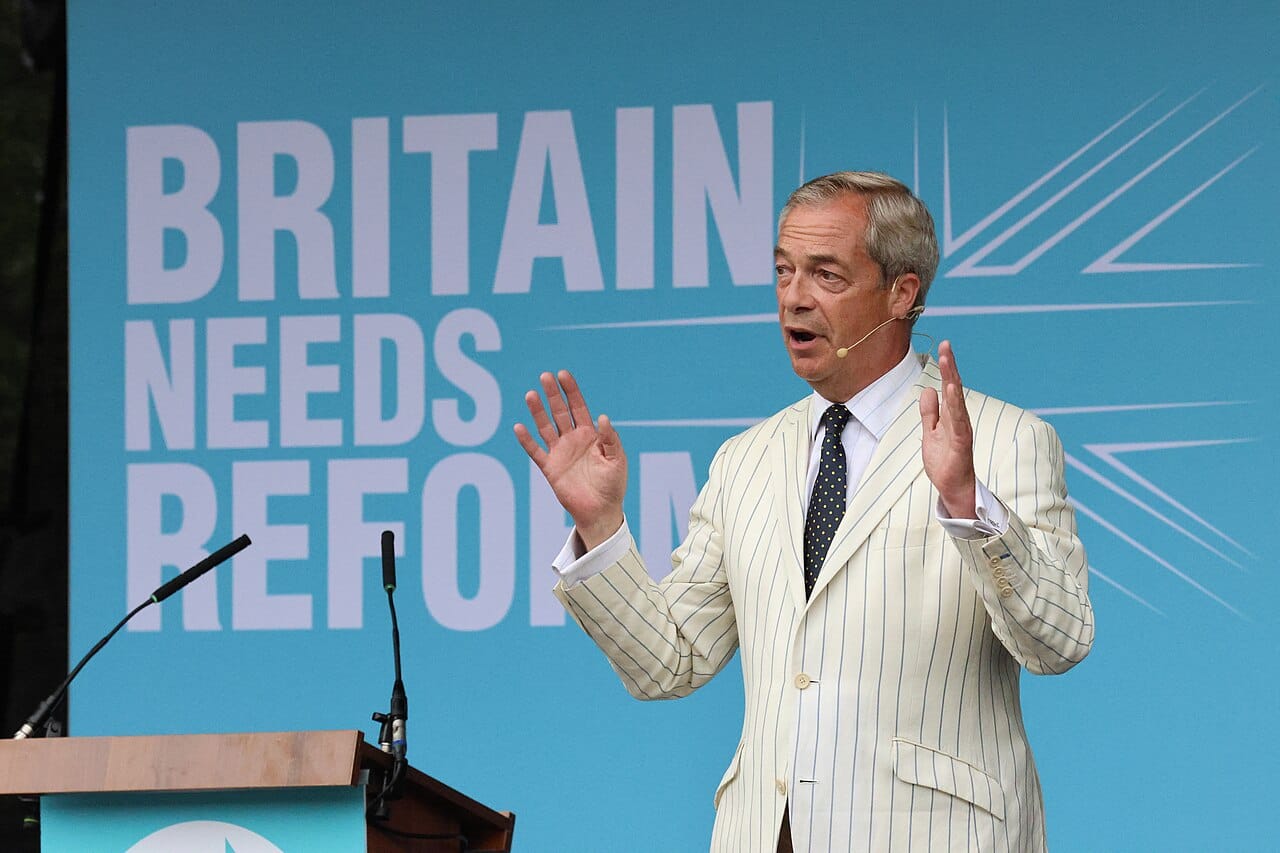

Across the Channel, bubbling right-wing currents were visible beneath the surface of Labour’s landslide election win in the UK.

The radical-right Reform UK – the ideological confrère of the Rassemblement National in France – gained almost 15% of the vote share in the UK. Only the first-past-the-post voting system prevented it from gaining more than five seats.

But in this regard, post-Brexit British politics is looking more “European” than ever.

France election: surprise win for leftwing alliance keeps Le Pen’s far right from power https://t.co/SdL9VNqCA5— The Guardian (@guardian) July 8, 2024

National security to the fore

Although the highest issue of voter concern in the UK election was the cost of living, national security was never far from the surface.

Questions of national security came to the fore when Reform UK’s Nigel Farage told the BBC’s Nick Robinson that he thought the West had “provoked” the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This shocked many people, but didn’t surprise those who have been tracking Farage’s politics, and those of the European radical right more broadly.

As Farage noted, he had long been of the view that the eastern expansion of NATO and the EU had given Putin an excuse to invade Ukraine.

According to Labour, the comments revealed “the true face of Nigel Farage – a Putin apologist who should never be trusted with our nation’s security”, while the former home secretary, James Cleverly, said Farage’s comments were “echoing Putin’s vile justification for the brutal invasion of Ukraine”.

Under Boris Johnson, Britain emerged as one of Ukraine’s most vocal and hawkish backers, aligning itself with the Nordic and Baltic states that fear they may be next to feel the force of Russian aggression if Ukraine falls.

The UK under Labour will remain steadfast in its support for Ukraine. Such support is seen as crucial in the post-Brexit quest for significance.

Quest for global relevance

Moral and strategic arguments aside, we shouldn’t discount the desire for global relevance; Britain must “punch above its weight”.

There are strong arguments in favour of continued support for Ukraine, but Britain’s establishment rarely makes them. The elite consensus has stifled any sense of informed and balanced discussion about the long-term prospects for the war.

In this context, many in Britain’s political and media class interpreted Farage’s comments as a misstep. It certainly put him out of step with the majority opinion.

According to polling published by UK In A Changing Europe, the British public is the least likely of 10 European publics to suggest the EU or NATO bears some responsibility for Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

However, it's also possible Farage had an eye on his post-election positioning, and his decision to confirm and defend his previous comments was an attempt to create a wedge issue.

The British public has been very supportive of Ukraine, but it’s important to remember that the public is generally sceptical about international conflict, considering the UK’s experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Foreign policy dissatisfaction

The rise of the pro-Gaza independents, the surge in Green Party support, and close calls for senior Labour figures in seats with large Muslim minorities are all indicative of growing dissatisfaction with British foreign policy.

It’s significant that there will now be leftward parliamentary pressure on the Labour Party that looked unlikely heading into the election.

The Labour Party’s strategy involved a marked shift to the right on several fronts as the party sought to placate socially conservative voters across the country.

This was clearly effective regarding seats, but it’s been widely remarked that with an unprecedentedly low 34% of the vote, Labour’s coalition is fragile.

The first election result in Houghton and Sunderland South was emblematic of the result across many Brexit-backing areas – with a 52% turnout, the now Labour Secretary of Education won 47% of the vote, while Reform and Tories together won 43%. Reform was second to Labour in 93 constituencies.

It’s unclear how the right-wing vote will consolidate, if it even does.

Nigel Farage hails Reform UK’s ‘almost unbelievable’ results in north-east England https://t.co/U8ntuZFw5x— The Guardian (@guardian) July 5, 2024

Farage set to challenge

Nigel Farage has been one of the key firebrands of British politics over the past 20 years. Now finally a member of parliament, he’s likely to mount a significant challenge to the structurally weak centre-ground of British politics.

The scale of this challenge will partly depend on the extent to which Farage can renounce his continued ideological attachment to Thatcherism and complete his far-right European transition.

Farage shares his longstanding admiration of Putin with some of Europe’s leading radical right figures, including Marine Le Pen and Viktor Orbán.

Add to this a politics opposed to immigration, Islam, net zero, and gender politics, and one of Britain’s most famous Eurosceptic politicians is arguably its most European.

In Britain and France, the centre has held for now, but it’s clear that incumbents face severe challenges; both countries remain beholden to structural forces that constrain their politics.

Liz Truss’ experience with the markets delivered a lesson that has been widely recognised and perversely celebrated by some. How politicians deal with these challenges will crucially impact the prospects for the radical right.