The news that a gas network is sponsoring MasterChef Australia this season to promote “renewable gas” and “low-emission alternatives” is only the latest in the long history of energy companies targeting domestic consumers and transforming public understanding regarding the use of fossil fuels.

“MasterChef Australia goes gas-tronomic!” reads BioEnergy Australia’s media release, promoting the use of “carbon-neutral biomethane”, captured from organic waste.

The cross-promotion has been criticised, not least because the biomethane used on the show is neither available for domestic consumption nor emissions-free.

It’s supported by a website touting the benefits of “renewable gas…as seen on MasterChef” and television advertisements highlighting the role of renewable gas in energy transition.

By sponsoring the latest season of MasterChef, the gas industry is pushing back on the ban of gas appliances like stovetops to promote biomethane and hydrogen — but experts say it's a cynical attempt to maintain control of infrastructure.https://t.co/UKuAdycfQO— ABC News (@abcnews) April 23, 2024

Critics see the sponsorship as greenwashing. Burning gas poses health risks for the home and the planet. And this gas is not “renewable”.

Yet, this two-year commercial sponsorship is part of a long tradition promoting gas to consumers and normalising domestic gas consumption.

The PR of cooking with gas

Even the popular catchphrase “cooking with gas” is supposedly the work of a public relations professional, Deke Houlgate, who worked for the powerful gas industry lobby group, the American Gas Association, and pitched it to Bob Hope’s radio comedy writers around 1939-40.

Delving into public relations history from the perspective of our fossil-fuelled present can offer insights into the ways promotional work has shaped energy consumption in the home.

In the late Victorian era, “lady demons” – female demonstrators – were employed to popularise the gas stove and address concerns regarding the dangers of cooking with gas.

Throughout the 20th century, energy companies engaged in extensive public relations campaigns to increase domestic consumption, attract new customers, and “educate” them about energy.

These campaigns, relying heavily on radio, cookbooks, women’s magazines, and later television, also contributed to public consensus regarding the use of fossil fuels.

Energy companies produced and distributed recipes, and ran demonstrations in their test kitchens and department stores.

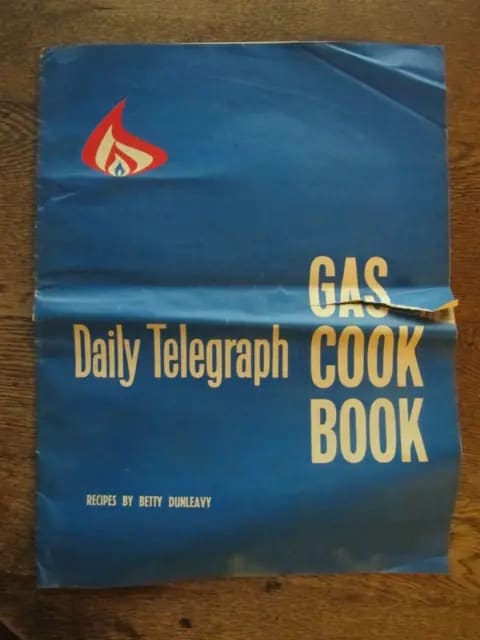

They published cookbooks, often in collaboration with media organisations, such as the Daily Telegraph Gas Cookbook (1964), a 32-page supplement to the newspaper, and South Australian Gas Company’s (1945-1959) Recipes: Gas The Wonder Fuel For Cooking, which featured its Home Service radio competition’s winning recipes.

The distribution of recipes was an effective public relations strategy, and home economists were in demand, creating new career opportunities for women to work in promotional roles targeting female consumers in the affluent post-war era.

Popular Australian cook and writer Margaret Fulton AM (1924-2019) wrote in her memoir that she was advised to get into advertising after the war as “food, energy and cosmetics will grow, and these will be the areas for the new progressive woman”.

Fulton’s first job in the food industry was at the Australian Gas Light Company, and in its Home Service Department she “gave cookery classes, conducted demonstrations, showed women how to use and save gas, and taught them about appliances”.

Like Fulton, some women built on this experience promoting to “housewives” to develop media careers as a result of the public profile through writing food columns and giving radio interviews, and later cooking demonstrations on TV.

In the 1980s, more men rose to prominence as television chefs. Among his many advertising and media roles, Peter Russell-Clarke was senior cooking demonstrator for the Gas and Fuel Corporation in Victoria.

Indeed, celebrity chefs have long attracted the interests of energy companies. Popular TV chef Julia Child’s 1978 television kitchen was provided by the American Gas Association. This high-profile product placement was part of a larger public relations campaign designed to promote gas over electricity at a time of growing concern over its environmental and health impacts.

“It’s now time for the inventive promotion of sustainable alternatives, given Australia has to stop relying on natural gas to have any chance of meeting its net zero target by 2050.”

It was only after drilling began in the Bass Strait that Victoria came to rely on “natural gas” for cooking and heating.

In 1969, Mrs Joy Westmore in Carrum became the first person in Victoria to have natural gas piped into her home, and the carefully staged moment – with Mrs Westmore stirring a pot on her stove – was captured by news photographers. Within the year, more than a million Victorian gas appliances were converted to use natural gas.

Public relations was unquestionably influential in naturalising the idea that gas was the first choice of the domestic chef – the housewife.

Throughout the 1970s, natural gas was promoted as both cheap and clean. Many people still view it as more benign, environmentally speaking, than coal. Despite its name, natural gas is a non-renewable fossil fuel energy source, and methane, a greenhouse gas, is its largest component.

Time to promote sustainable alternatives

In 2024, the shift away from gas in Victorian homes, where 80% of households rely on gas, is accelerating, and gas connections in new homes are now banned.

It’s now time for the inventive promotion of sustainable alternatives, given Australia has to stop relying on natural gas to have any chance of meeting its net zero target by 2050.

Last year, MasterChef Australia judge Melissa Leong – who Network 10 dropped from the lineup this year – helped promote electric induction cooktops as an ambassador for the Global Cooksafe Coalition, which promotes safe and affordable fossil-free cooking.

In the UK, Italy, Denmark, and Spain, MasterChef has already shifted to electric induction cooktops.

The cross-promotion with MasterChef Australia to promote “renewable gas” is a cynical exercise, as the gas industry seeks to protect its assets and navigate a new energy future.

It’s not just greenwashing – it’s gaslighting.