Not long ago, news outlets carried headlines announcing even small outbreaks of COVID-19 infection. Now, infections have become so common that they’re hardly newsworthy.

The shift in the Australian federal government’s policy announced in late December 2021 – from ‘‘suppression with a goal of no community transmission’ to a ‘living with COVID-19’ context where the community is able to function more normally and disruptions to society and community are minimised” – reflects a substantial change in perceptions of the disease, risk and responsibility.

The “living with COVID” public health strategy, it’s claimed, is based on the realisation that the elimination of the virus is impossible, and that consequently people need to adjust to a “new normal” and take greater responsibility for managing their own relationship to risk.

Last November, when it was announced that some state borders would soon open, some experts argued that “we’re all going to get COVID”, but people would “only experience a mild illness”. But by what standard is the illness judged to be “mild”?

It’s now known that COVID-19 may involve ongoing debilitating symptoms (“long COVID”) that may persist for months, although studies suggest these may decrease after vaccination.

Many people, including those in my networks who have had COVID, will tell you that the illness is not “mild”. No doubt there are people with COVID who have few or no symptoms and go about their business – infecting others in the process – who may also suffer long-term symptoms that may never be linked to the disease.

The short and longer-term impacts of the illness on individuals, families, workplaces, and the economy are immeasurable.

Testing, testing testing

A key plank of the “living with the virus” strategy is mass self-testing using rapid antigen tests (RATs) (or “at-home” tests).

Read more: Down the RAT hole: the policy disaster of relying on Rapid Antigen Tests

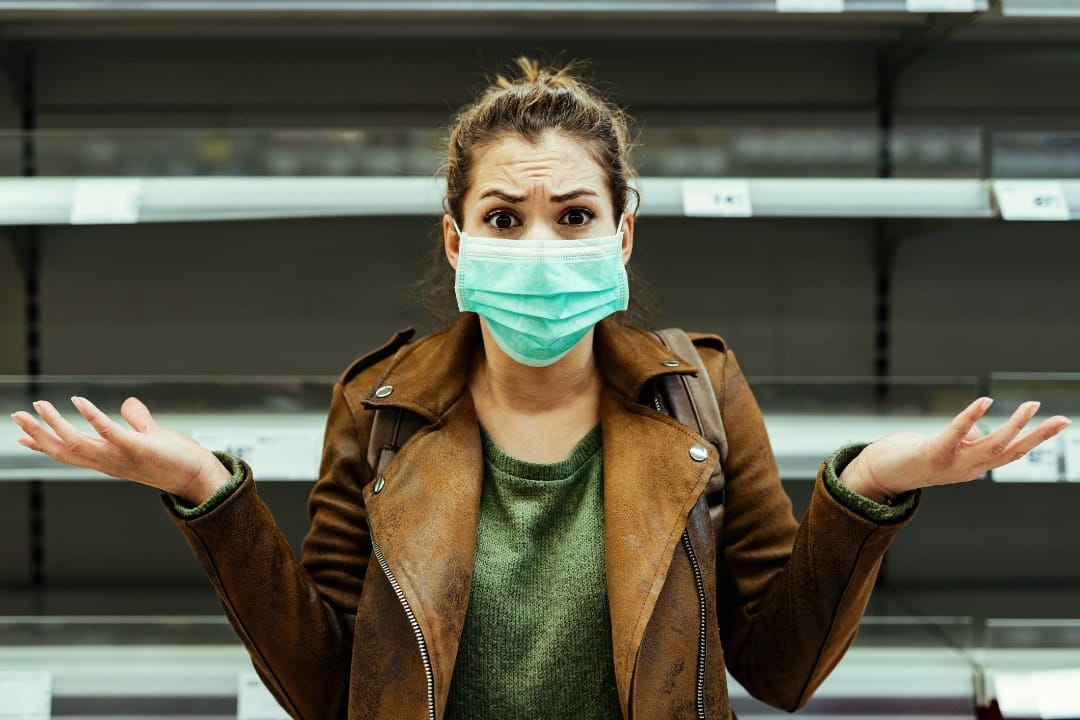

In rolling out the strategy, authorities have assumed citizens will act responsibility by using the tests (which were in short supply to begin with), then act on the results in prescribed ways – namely, taking a follow-up PCR test if the RAT results are positive, self-isolating, monitoring one’s symptoms, advising close others, and so on.

But this strategy is based on naïve views on the factors that shape human actions.

People belong to communities that influence outlooks and actions in different ways, and their financial and personal circumstances may vary considerably.

The strategy overlooks the fact that individuals may have difficulty using the tests (perhaps because they’re blind or have low vision), and/or may misinterpret the results or not be able to afford to take time off to isolate.

In some cases, self-isolation may not be feasible. For example, some people may be in a large family that lives in a small house with one bathroom.

Much can go wrong with a strategy that relies on RATs, including the production of false positives and false negatives, which can lead people to make decisions that carry risks to themselves and others. There’s great variability in the sensitivity of different brands of RATs – and 47 have been approved in Australia so far. Can people place equal confidence in all these tests?

Pandemic fatigue

The “living with COVID” strategy has been attributed to growing “pandemic fatigue” noted in many countries.

In Victoria, it accompanies the dismantling of the central pandemic bureaucracy – at a time when the healthcare system is confronted with a surge of both COVID-19 and influenza infections, and falling vaccination rates.

The strategy is reported to have “less to do with epidemiology than budgetary considerations” in that the workforce employed to help deal with the COVID-19 surge was mostly hired on fixed-term contracts that are due to expire at the end of June 2022.

It had been announced that other “largely redundant COVID bureaucracies” are also being wound up by the end of the financial year.

There would seem to be many factors, apart from “pandemic fatigue”, contributing to the shift in strategy, including that much of the population has had at least two vaccinations (which has instilled confidence that fewer people would become seriously ill), and recognition that the Omicron virus and its sub-variants are too infectious to control through measures such as contact tracing.

Growing community resistance to social restrictions, including the use of face masks in public settings, and concerns about the mental health consequences of COVID-related measures, have also undoubtedly played a role in the decision to change course.

In the event, the strategy has been accompanied by unclear and often mixed messages that have contributed to public confusion, which has arguably placed people’s health at risk.

Mixed messaging can be seen in the Australian Health Protection Board’s (AHPPC) statement on face masks, published on 14 June, 2022.

The statement begins by noting that it “revised the need for mandated mask wearing in certain settings” (noting that “all states and territories have relaxed mandates in most settings within the community”) and “considers that it is no longer proportionate to mandate mask use in airport terminals”. Yet, in the paragraph that follows, the AHPPC notes that it:

“... continues to recognise the role of masks, along with other public health measures, in minimising COVID-19 and influenza transmission and protecting the broader community, including those who are unable to get vaccinated and people who have a higher risk of developing severe illness.”

And that therefore:

“... the AHPPC continues to strongly recommend continued mask wearing in airport terminals and other indoor settings, especially where physical distancing is not possible.”

It’s no wonder that many people are confused by what they need to do to prevent infection, and that some have decided to “do their own thing”.

From the beginning of the pandemic, infection control policies have been underpinned by a series of utilitarian calculations of the potential benefits of actions versus their potential costs or harms.

This includes the use of lockdowns, face masks, vaccines, and tests. The principle of utilitarianism, which can be traced to Jeremy Bentham, has taken many forms, and has been refined so that there are now many versions.

But the broad premise is that one should evaluate actions according to their consequences; that by identifying the various possible courses of action that could be performed, and the related benefits and harms from each, one can determine the course of action providing the greatest benefits (taking into account the costs).

Utilitarianism has underpinned many, if not most, public health policies in the past, including the introduction of fluoride into our water supply (to prevent dental caries), and the vaccination of children (to achieve “herd immunity”).

The “living with COVID” strategy, likewise, is underpinned by a utilitarian logic.

The problem with utilitarianism is that the consequences of different strategies can never be entirely foreseen. Policymakers have drawn on epidemiological models to assist them (for example, calculating the number of probable infections or deaths resulting from certain measures), but the models include biases and assumptions that may – and often do – prove to be naïve, wrong, misleading, and/or discriminatory in practice.

The strategies have involved the use of different technologies, including QR codes, test and trace, and so on, which also embody biases and have discriminatory effects.

As it happened, the lockdowns generally suited people who could work or study from home using digital media, while disadvantaging those who didn’t have this option.

The rollout of vaccines brought into play another set of utilitarian calculations regarding potential community benefit of vaccinations versus incursions on individual freedoms (namely, not to be vaccinated).

The strategy gave rise to resistance and marginalised and demonised certain groups – outcomes presumably not foreseen by policymakers.

Trade-offs of time and efficiencies

The most recent shift in COVID strategy from relying on PCR “gold standard” tests to relying on RATs has involved a similar set of trade-offs in terms of time and cost efficiencies. (The PCR tests were slow to process and involved huge investments of staff time to process the results; RATs produce quick results, and the costs for their purchase are mostly shouldered by consumers.)

But there’s been little public debate about what’s involved in these various trade-offs, and who ultimately benefits and who is disadvantaged in the process.

It’s doubtful that policymakers who are confronted with a major public health event such as COVID-19 and its related uncertainties can ever “get it right” in terms of developing a strategy that achieves desired health outcomes while avoiding unintended consequences.

However, their decisions will be improved by recognising and publicly acknowledging the various trade-offs involved in different decisions, and avoiding knee-jerk political responses justified via the selective use of science and expertise, as often happened over the past two years.

Public health policies need to incorporate mechanisms for public deliberation on the issues at stake in different courses of action, since the consequences for people’s health and wellbeing are likely to be profound.