Facebook has been described as the most powerful behavioural modification machine in history. The “Facebook Papers” exposé in October 2021 alleges the social media giant was aware its algorithm changes were making users angrier, and might even have been inciting violence.

In 2018, Facebook made a major change to its algorithm. Co-founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg stated the aim was to improve user wellbeing by fostering interactions between friends and families.

In September 2020, a former director alleged Facebook had made its product as addictive as cigarettes. He feared it could cause “ civil war”.

Internally, there were concerns Facebook was not doing enough to curb the “Stop The Steal” movement on the platform. A few months later, on 6 January, 2021, a mob attacked the Capitol building in Washington DC.

Facebook is a trillion-dollar company built on advertising revenue and user engagement. It was concerned users were scrolling rather than engaging – this posed risks to its advertising model. The algorithm change was designed to decrease disengagement by prioritising comments rather than just scrolling or a “like”.

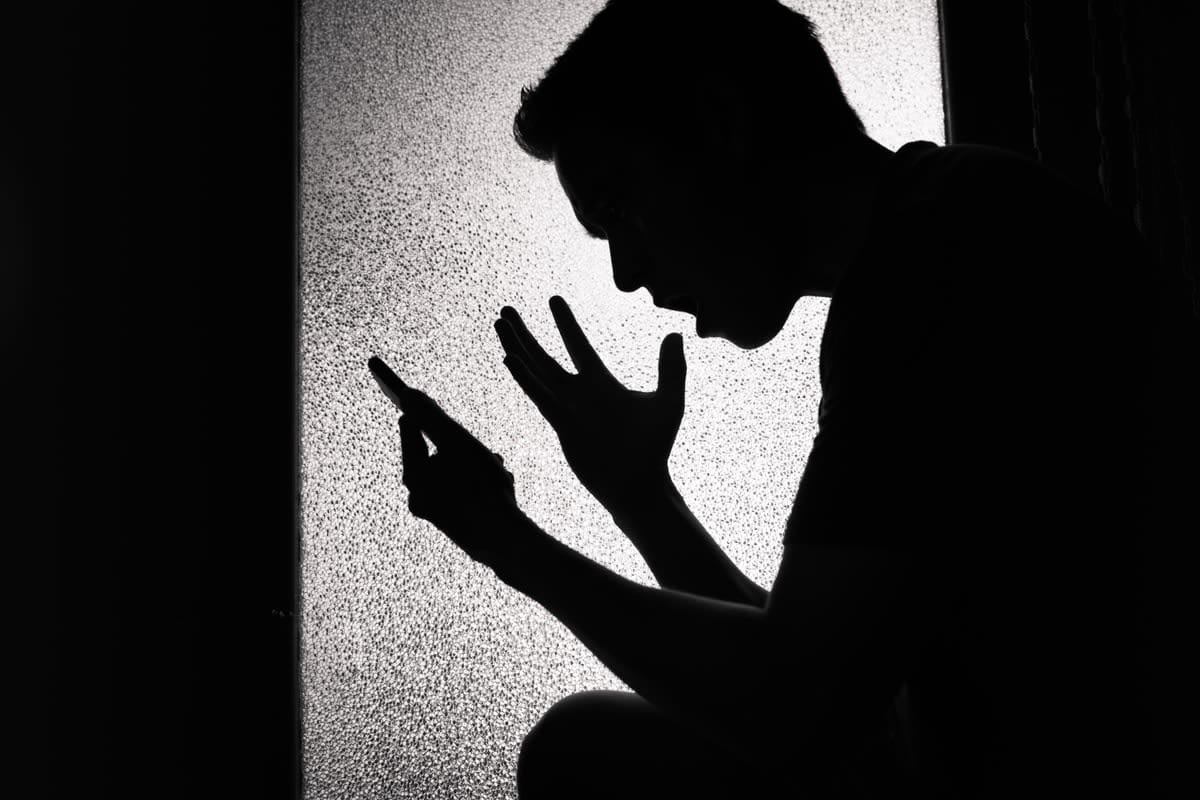

The problem is that it’s divisive content that’s most likely to attract comments. The algorithm “preys on the most primal parts of your brain [and] triggers your strongest emotions”. When you see something that you disagree with, you feel compelled to respond.

The result was that divisive content was hotwired into the system. Users respond to outrage content, advertisers follow, and publishers prioritise divisive content.

It seems that the more users hate, the more Facebook profits.

Autonomy has been compromised

It appears the autonomy of users is being compromised. Autonomy involves being able to make our own choices, according to our motives, rather than due to distorting external forces.

Social media platforms exert considerable influence over users through:

- outrage algorithms

- a long-term relationship with users, and possibly addiction

- having deep information on them

- pervasive use of behavioural-influencing science, including the “holy grails” of:

– when we’re vulnerable to influence identifying moods

– identifying subconscious cues such as a hovering cursor that shows interest levels

– deploying “dark patterns”, such as obstruction, in their architecture to herd users.

Sometimes the influencing or architecture is “manipulative” – that is, unethical, in that it covertly influences a user.

Data privacy laws not the answer

Data privacy laws don’t appear to provide a solution. They emerged in the Information Age in the 1950s, when technology enabled detailed data collection.

DPLs apply only when “personal information” – information about “an individual who is reasonably identifiable” – is collected and held.

While DPLs once indirectly protected autonomy, they’re now being outpaced.

First, the volume of information on individuals has exploded; social media knows more about you than your best friend. Accessing thousands of pages of raw data about yourself is simply not empowering.

Second, the most valuable information, namely profiling or analysis, might not be “personal information”. A traditional profile is actual information, indexed to an individual so that it can be used, and therefore falls under DPLs.

Modern “de facto profiling” involves an algorithm using big data to make inferences about characteristics of a person.

In this new paradigm, what’s valuable are characteristics, and not identity. Facebook knows someone’s moods. Uber knows if a passenger has been drinking. In these examples, the person’s identity may be protected, and they remain unidentified, but what’s valuable to the platform is their characteristics.

What is ‘unconscionability’?

That doesn’t mean the legal toolbox is empty. It may be that Facebook’s outrage algorithms are unconscionable. Unconscionability is “conduct that is so far outside societal norms of acceptable commercial behaviour as to warrant condemnation”.

It’s informed by values in Australian society including respect for the dignity and autonomy of individuals.

To be fair, Facebook doesn’t produce divisive content – but it prioritises it. Although the threshold is very high, Facebook’s conduct is arguably unconscionable:

- Given that its relationship with users is based on asymmetric information and influence. It may be exerting undue influence over some users, such that users’ conduct aren’t “free acts”.

- It’s using unfair tactics. Zuckerberg’s 2018 announcement appears to be misleading. Prioritising outrage without informing is manipulative and tainted by a high level of moral obloquy. An exacerbating feature was Facebook’s initial denial that the algorithm existed.

- Users’ dignity and autonomy aren’t being respected. We’re agitated by the outrage and act on it.

That Facebook’s conduct has been the subject of severe criticism suggests it’s far outside societal norms. Ultimately, this article argues that manipulatively fostering divisiveness on a mass scale in order to profit, knowing that it may be inciting violence, is unconscionable.

If platform behaviour-influencing remains unchecked, there’s a danger that we reach a point when, as Zuboff warns: “Autonomy is irrelevant … psychological self-determination is a cruel illusion.”