Up for the count: Women authors reach parity in the review stakes

Harvey

The line in the sand was drawn in 2011 when the shortlist for Australia’s premier literary award, the Miles Franklin, was again all-male. It was dubbed in some media a “sausage-fest”. The following year, the Stella Prize for women writers was established.

“That was the beginning of the conversation,” says Monash University’s Dr Melinda Harvey, a lecturer in English who, shortly after, began collaborating with the Stella Prize on its Stella Count, which quantifies gender bias in Australia’s literary sphere by examining the books pages of the major newspapers and magazines.

“Why are there so many women working in publishing, reading books, writing books, and yet we get a list like that Miles Franklin in the prize sector? This is why the Stella Prize and the Stella Count were founded.”

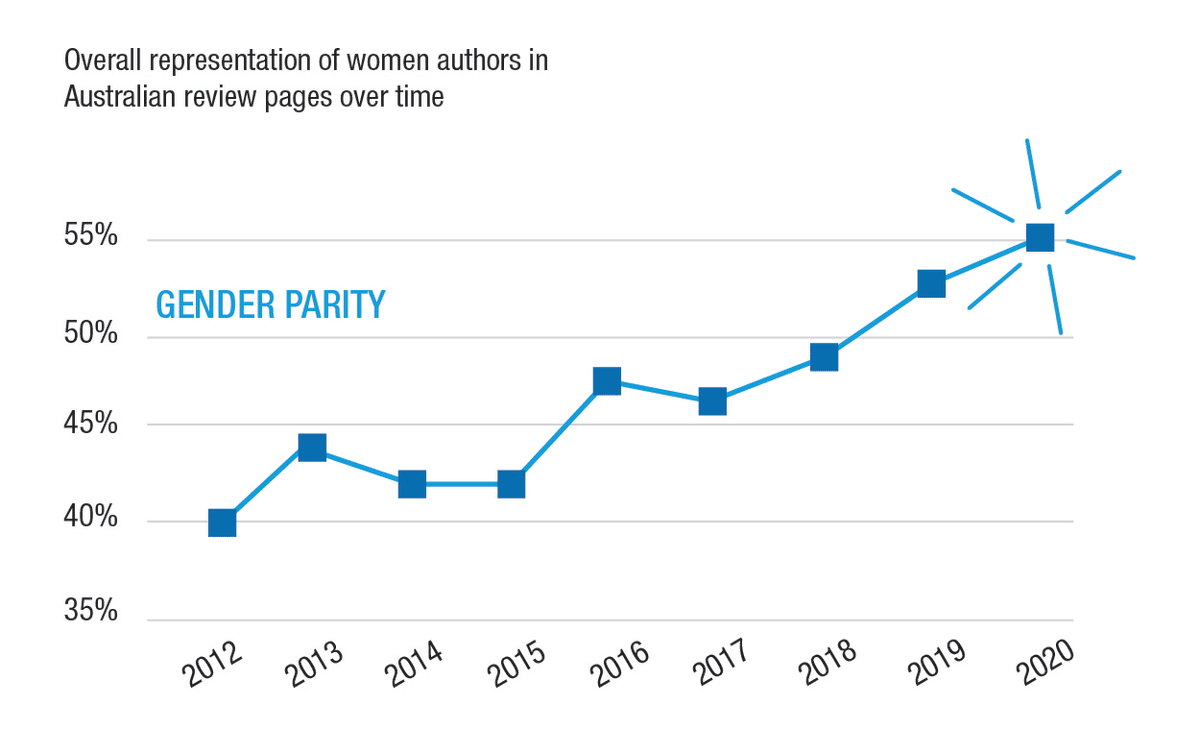

Now, a decade on, the numbers have revealed a landmark moment in which women authors have not only reached parity with male authors in terms of books reviewed, but exceeded it.

The latest Stella Count, released today, includes two counts, as it was COVID-delayed for 2019 and 2020 – they show 53 per cent then 55 per cent of all books reviewed in 12 mainstream media and literary publications were from women authors. This is an increase from 49 per cent for 2018.

“We had almost reached population parity in 2018. Now we have this dual edition of the Stella Count, and we see the number of women authors reviewed exceeding the population parity line of 50-51%. As we say in our report, it's crashing through that barrier now.”

Women authors dominate Australian publishing

Dr Harvey makes the distinction between population parity and publishing parity, as women – as authors and readers – dominate the Australian publishing scene.

“It’s hard to get a figure on how many new books by women get published each year in Australia, but women constitute about 65% of today’s Australian authors total. So if you measure this against the reviewing of women authors in our publications surveyed, it hasn't yet reached that line.”

Still, it’s highly significant. “It's possibly indicating that Australia has the most gender-equal book reviewing scene in the world, but we can't know that for sure,” Dr Harvey says.

The beginnings of the Stella

In the UK, the Orange Prize – now called the Women’s Prize for Fiction – was launched in 1991 after an all-male Booker Prize shortlist that included Martin Amis, Roddy Doyle and winner Ben Okri. The Australian Stella Count emerged from all-male Miles Franklin shortlists in 2009 and 2011; in 2009 it was a roll-call of the familiar, with establishment surnames of Winton, Flanagan, Nowra, Bail and Tsiolkas.

This is despite Miles Franklin being a woman author, with the full name of Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin – hence the Stella Prize and Stella Count. When they set up in 2012, a woman had won the Miles Franklin only 13 times in 54 years, with four of those Thea Astley.

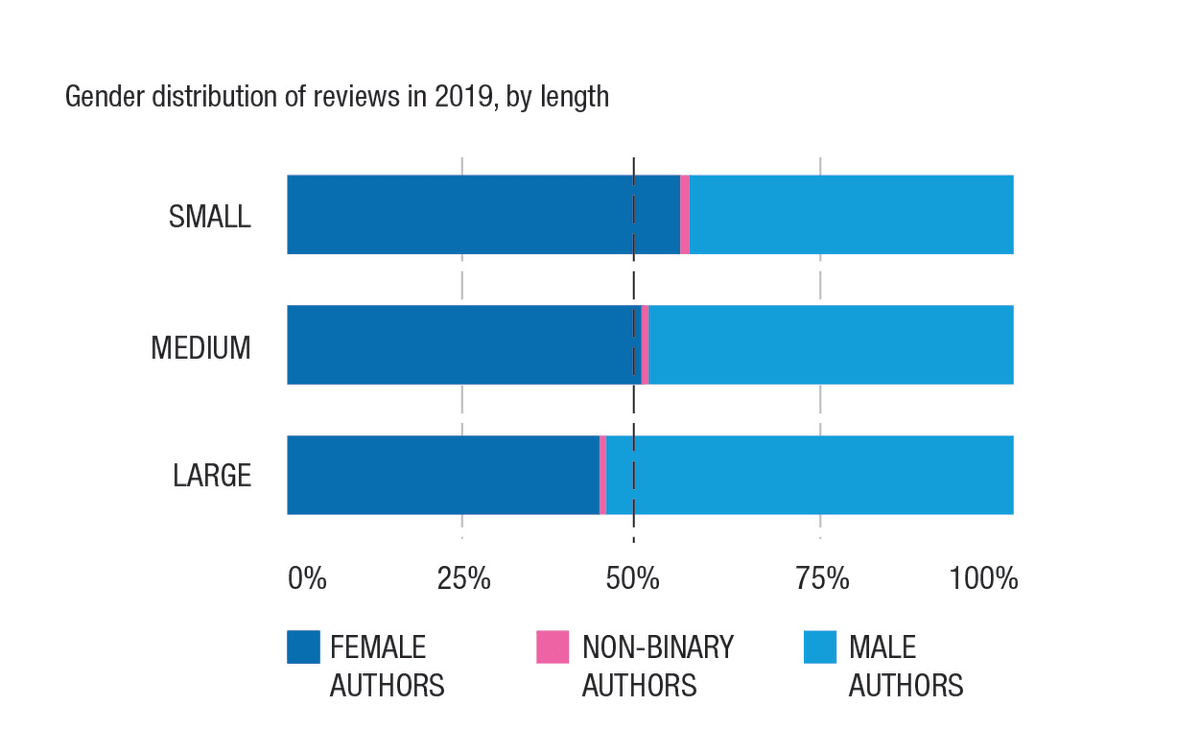

Dr Harvey conducts the count with Dr Julieanne Lamond of the Australian National University. As well as the overall top-level percentage of women authors being reviewed, they break the count into categories such as the gender of reviewers or book critics, review length and gender, genre and gender, and a detailed breakdown of the 12 publications they scrutinise.

The publications for the newest counts were The Advertiser in Adelaide, The Australian’s Weekend Review, Australian Book Review, the Australian Financial Review Magazine, Books+Publishing, Brisbane’s Courier Mail, Hobart’s The Mercury, The Monthly, The Saturday Age and SMH, The Saturday Paper, the Sydney Review of Books and The West Australian.

“There's this longstanding idea that women don’t write serious books that demand the attention of the critics.”

Stella’s Executive Director, Jaclyn Booton, says of the findings:

“As we reflect on Stella’s impact since 2012, results like the Stella Count show that sustained, targeted accountability measures do work in driving systemic change. We’re thrilled to be presenting these findings, and look forward to a brighter, more equitable future for Australian women and non-binary writers.”

The question of gender identity is a complex one in this context – non-binary writers have not been included in the count until this year when eligibility became more inclusive.

When the count was started, Dr Harvey explains, she and Dr Lamond thought that underneath the numbers was a bigger cultural story to be told.

“For example,” she says, “in the 1980s there was a kind of watershed moment in Australian publishing where a lot of women were getting published – people like Helen Garner, Kate Grenville, Elizabeth Jolley and others.

“We started to wonder, well, is this actually a worse moment for women than that? Have we gone backwards? How do we understand this moment in our history compared to what we thought might have been the high-water mark of women or feminist publishing in Australia?”

Who, what, where taken into account

In the detail is data on who reviews what, and where, and at what length.

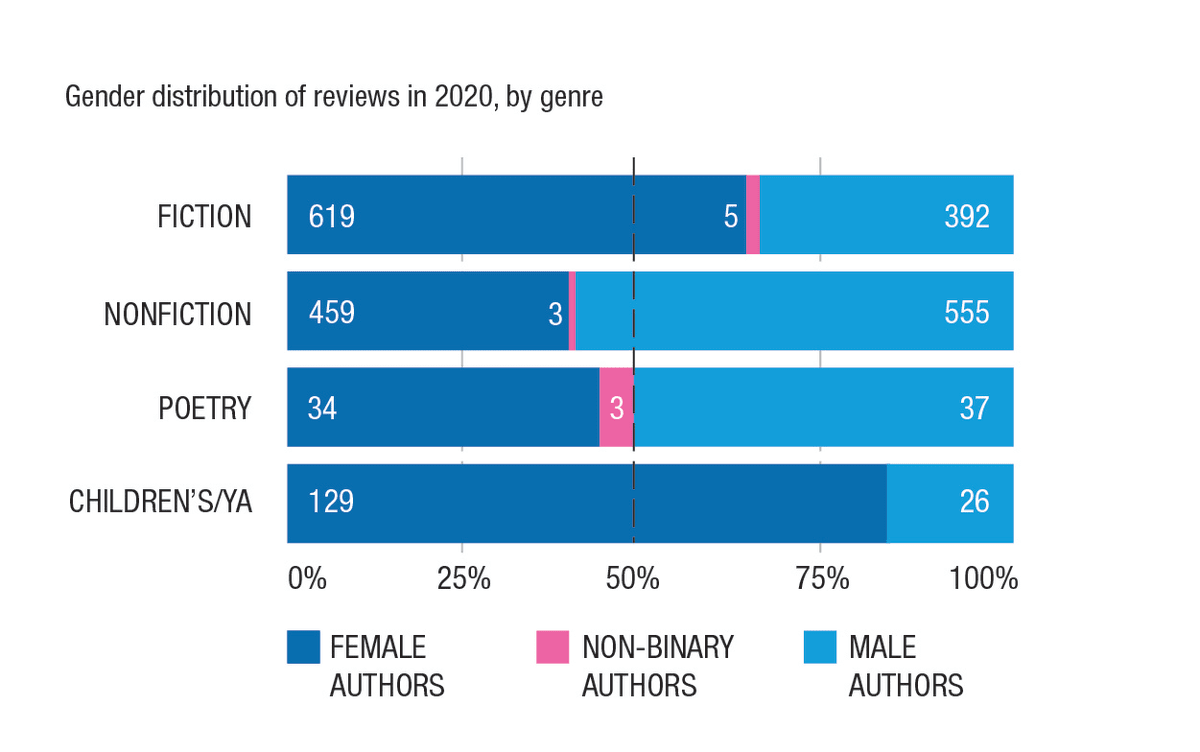

“We count the genre of books reviewed, and we've noticed that women critics get a large proportion of the fiction reviews in the outlets that we survey, and also children's and young adult literature by women is reviewed strongly,” Dr Harvey says.

“There's this longstanding idea that women don’t write serious books that demand the attention of the critics. Men write the books about politics and war or world events. There’s been a prestige aspect in play, where men write big important books, and women write the rest, or women write about the home.

“But what we’re starting to see in the stats in the new surveys is that women are gaining attention and acclaim in non-fiction now due to a surge in the publication of women’s essay collections and memoirs. Women are coming into the field of non-fiction more this way, and these books have attained a literary status now.”

The Stella Count is literally a count, meaning it publishes statistics based on data collection.

“One of the main reasons the Stella Count was established was because many women anecdotally felt that there was something unequal about the literary sphere in Australia, but didn't have the stats to back up that hunch,” Dr Harvey says.

“Stats have a hardness about them. Stats and data are sometimes used in feminist activism in this way, as a way of talking back to power in a language that power understands. Stats take things out of the realm of perception and individual stories about disparity or bias.”

About the Authors

-

Melinda harvey

Lecturer, Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts

Melinda completed her Bachelor of Arts (Hons I) and PhD in English literature at the University of Sydney. She’s previously held lectureships at the University of Sydney, European College of Liberal Arts, Berlin (now Bard College, Berlin), ANU and RMIT University. Her research focuses on women’s writing, especially in its intersections with modernism, the post-45 New York intellectuals, and the contemporary literary scene. She’s an established book critic, writing for the major Australian newspapers and literary magazines, and in 2020 was a finalist for the Pascall Prize for Criticism, Australia's only award for arts criticism. She’s been a judge of the Miles Franklin Literary Award since 2017. She collaborates with Dr Julieanne Lamond (ANU) and the Stella Prize on the Stella Count, which quantifies gender bias in the book pages in Australia.

Other stories you might like

-

Talkin’ all that jazz: Unsilencing gender in music

Research, education and music practice need to be aligned to ensure women's voices in jazz are heard.

-

The discovery disconnect

The economic and social consequences of the COVID-19 crisis have reinforced gender inequality across the globe – as shown in the medical research field.

-

A path to potential

A new advocacy group aims to address gender imbalance in science by helping map the career trajectories of early-to-mid-career researchers through promotion of their existing research achievements.

-

Caught between #metoo and the gun-show

Hyper-masculinity is a defining feature of global politics, but the #metoo movement is prising open opportunities to pursue gender equality as women fight back.