As many Australians come out of lockdown restrictions, they face a host of new checkpoints – at shops, the workplace, entertainment venues and state borders.

Not only do many of us have to check in at various locations by scanning QR codes, we’re now required to show proof of vaccination and, in some contexts, proof of negative COVID-19 tests.

The result has been the increasingly familiar site of people fumbling with smartphones on the sidewalk in front of whatever space they’re trying to enter. In some cases, it can mean frustrating bouts with apps (“What was the PIN code for the Medicare app?”; “Have I linked it to my MyGov account?”; “Where’s that text with my test results?”; “Uh-oh ... my battery is dying!”).

Australia isn’t alone. The pandemic has contributed to a new set of protocols for travel and access of all kinds – all in the name of controlling human circulation to thwart that of the virus.

These new layers of verification and control set the stage for a technology that offers to cut the Gordian knot of passwords, usernames, PIN and QR codes, as well as passports, vaccine cards, and paper tickets – biometrics.

Building on the success of the use of facial recognition technology for border control, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) has introduced a travel pass initiative that would enable “seamless” transit while adhering to pandemic restrictions. In keeping with the IATA’s claim that “the future of aviation is biometric”, its “One ID” solution would not only identify a passenger’s travel credentials, but would link these, internationally, to travellers’ vaccine status, test results, and/or “proof of recovery”.

The “One ID” solution addresses an issue that’s not limited to air travel – or the response to COVID-19 – but is exacerbated by the prospect of travel during pandemic times.

More generally, we find ourselves navigating a growing array of login prompts and checkpoints both online and off. According to some estimates, the average person with access to smart devices and online resources has about 100 passwords – and this number is growing rapidly. The proliferation of online services may ease access, but it throws up speed bumps in the form of access credentials – as anyone who has ever had to reset their two-factor identification system has likely discovered.

We use passwords to watch TV and movies, to access the bank, the library, our books, our email, our newspapers, the intranet at work, our children’s report cards, our shopping sites, our internet service provider, our government services account, our highway toll account, our music, our social media accounts, our online games, our documents and calendars, and on, and on, and on.

The ongoing attempt to control the spread of COVID-19 means that physical space will become more like password-protected spaces online; we’ll need to show credentials to verify our immunisation status and to mark our movements as we go through the course of our daily lives – showing up at work, going to a café for lunch, or a theatre in the evening.

These multiplying forms of “friction” in moving through physical and virtual space set the stage for a unified biometric solution – a technological response to the digital hurdles multiplying around us.

The “One ID” solution envisioned by IATA for airline travel anticipates a world in which, instead of fumbling with passports and other forms of ID, we’re recognised by automated systems that allow us to move seamlessly through these checkpoints.

Biometrics could also ease access to our various online services and accounts, dispensing with the need to remember or store passwords, and allowing us to move seamlessly from device to device.

We’re invited to imagine what it might be like to dispense with passwords, ID cards, metro cards, drivers’ licences, check-in apps, and more.

The promotional material of facial recognition companies is jam-packed with descriptions of systems that allow people to move seamlessly through checkpoints from retail checkout counters to train stations and secure workspaces where distributed sensors ”recognise” them, linking to their profiles and even their bank accounts.

Biometrics could also ease access to our various online services and accounts, dispensing with the need to remember or store passwords, and allowing us to move seamlessly from device to device.

Such solutions are still some way off, but we’re already starting to see the more widespread deployment of a range of biometric solutions.

The Australian government, for example, continues to work towards the widespread deployment of a nationwide facial recognition database – a database that is reportedly already being used by some police despite the lack of enabling legislation.

It’s also incorporating facial recognition technology into the MyGov platform for accessing government information and services. To the extent that such a rollout is successful, the result could be a move towards biometric identification as the default mode of authentication for everything from accessing tax information to commercial sector transactions such as opening a bank account and signing up for broadband access.

Biometrics and the security risks

The time to consider the implications of the widespread use of biometrics is now. Biometric data collection can be highly invasive, and it’s important to ensure it’s being used responsibly and proportionately. It may seem liberating to be able to step into a shop, pick up a carton of milk, and pay automatically with your face, but much depends on how your information is collected, stored, and used.

The widespread collection of biometric data could result in data troves of personal information that create a security risk. When biometric information is compromised, the results can be a lot more difficult to address than, for example, the fallout from a leaked password. You can’t call up the IT department and get them to reset your face.

Moreover, biometric data can provide detailed information about people that goes far beyond simply identifying them. Because biometric sensors, by definition, rely on data about bodies, they can be used to determine information about people’s state of health, for example.

Some researchers claim to be able to determine information about people’s moods, intentions, and state of mind from biometric data. This is a lot of information to give away in exchange for a carton of milk – and it lends itself to a host of possible abuses.

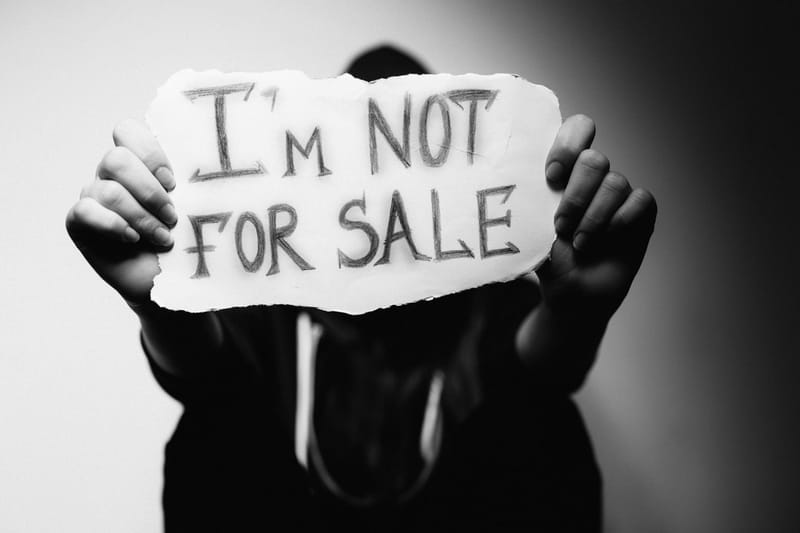

The temptation of being able to seamlessly navigate the information checkpoints and borders that are restructuring our online and offline lives is a powerful one. But a biometric solution needs to be treated with caution and care. Centralised solutions enable centralised control – and using our bodies as universal passports raises grave concerns for control over personal information and bodily autonomy.

Read more: Facial recognition survey reveals concerns about accuracy and bias

We’ve grown used to a certain level of “wiggle” room when it comes to personal identification in many contexts. Much to the chagrin of commercial information providers, for example, we can share our passwords for newspapers, streaming services, and other forms of online access. We can still make purchases with cash (in many places) without leaving a record of our movements, our preferences, and our habits.

This wiggle room may pose risks of abuse – but it also keeps us from feeling we’re being constantly monitored and controlled.

This article was co-authored with Professor Gavin Smith, School of Sociology, Australian National University.