Today’s Australian fathers are believed to be more “hands-on” and engaged with their children than the stereotypical absent breadwinner of generations past.

However, our research exploring Australian fatherhood between 1919 and 2019 has found that while men’s family roles have changed, deep-rooted societal and cultural forces keep them from being the kind of fathers many of them would like to be.

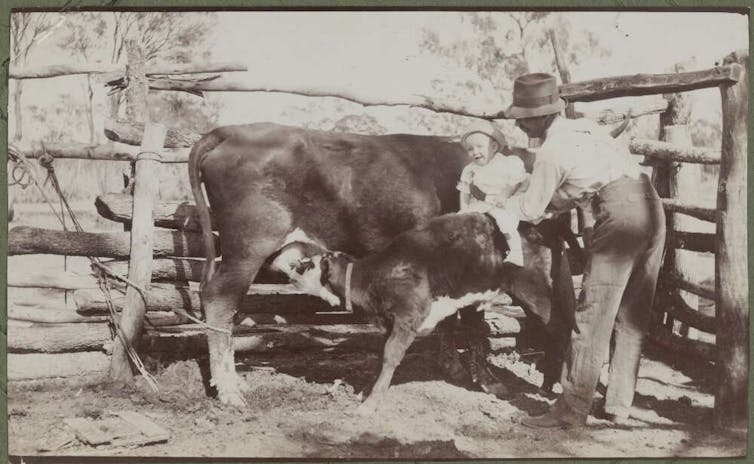

The breadwinner of the early 1900s

Our research examined oral history interviews with (and about) fathers from diverse backgrounds, along with archival sources including letters, diaries and government files. Our goal was to better-understand the experience of Australian fathering over the past 100 years.

We found a key factor shaping the history of Australian fatherhood has been the demands of paid work and the enduring power of the provider role – even in situations where dads aren’t the sole earners.

While the breadwinner father is hardly a uniquely Australian phenomenon, the ideal became institutionalised here in distinctive ways.

The 1907 Harvester Judgement, a landmark court ruling, established the principle that the male basic wage should support a wife and three children. This decision, which in turn ensured lower wages for women, remained the basis for setting Australia’s minimum wage until the 1970s.

Male breadwinner assumptions shaped not just the country’s wages, but also welfare and tax policy, so that it simply made better financial sense for fathers to work and mothers to stay at home with the kids. This entrenched a gendered division of labour in family roles that would last for generations.

The Great Depression then made many fathers failed breadwinners. Geoffrey Ruggles, who was born in rural Victoria in 1924, recalled in an oral history interview that when his war-veteran father lost work, his mother was “forced to scrub other people’s washing”.

Humiliation fuelled marital discord and damaged Ruggles’ relationship with his father. He found an alternative father figure in his navy officer uncle:

"[My uncle] had a lot of glamour about him […] an extrovert, a bright outgoing, merry man. A contrast to my father who was a sad sack. So Uncle Tom was a great fellow to be with, he gave me tools and helped me to start things like that, and fostered an idea of innovation – of doing what I wanted to do."

The sons of struggling Depression-era families often grew up determined to be good providers for their own families.

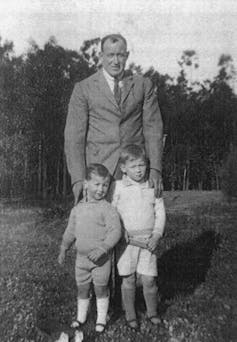

Many were also veterans who sought the stability of “traditional” family life. These men became the stereotypical, Holden-driving, breadwinner fathers of the “imagined fifties”, counterpart to the stereotypical 1950s housewife.

These stereotypes aren’t entirely wrong. The sole-breadwinner father is often assumed to be the historical norm, but in fact this family arrangement was broadly achievable for only a brief time between the early 1950s and 1970s. For the only time in Australian history, many working-class families could manage on one wage.

By the mid-1970s, however, recessions, deindustrialisation and the casualisation of the workforce shattered the economic security of the (male) “job for life”. At the same time, feminism and equal pay were mounting a new challenge to the male breadwinner stereotype.

The ‘new man’ of the late 20th century

History is so often circular. The sons of the postwar, breadwinner fathers wanted to do things differently from their dads, too.

In another oral history interview, Peter, a man born in Melbourne in 1956, recalled:

“As a teenager in the 1970s […] most of the guys that I knew had lousy relationships with their dads. And I think that was really common […] a lot of them had been to war, they’d come home and their role was to build a family, you know, build a financial basis for it, so they worked long hours and they just really didn’t seem to relate to their sons.

“We all got on really well with each other’s mothers. But the fathers were very distant figures, and it’s very different from today.”

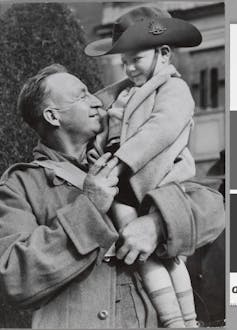

The social, cultural and economic transformations sweeping Australia from the mid-1970s brought new opportunities and expectations for fathers. Feminism and the growing numbers of working mums challenged traditional gender roles in families, and contributed to the emergence of the popular ideal of the “new man” by the 1980s.

Fathers of this generation were more likely to be present at the births of their children, and to be physically and emotionally “present” dads.

The inevitable outcome of these changes, some assumed, would be a dual worker-carer model of family life in which mothers and fathers have more equal parenting roles.

Read more: How Hemingway felt about fatherhood

The ‘modified breadwinner’ family

Yet, today’s fathers still find their working lives to be a significant barrier to their ability to be active and engaged fathers.

Since the mid-1990s, the most common family formation has been the “modified breadwinner” model. Mothers typically return to work after having children, usually part-time, while the full-time working father earns the primary wage.

Although fathers are caring for children slightly more than in the past, time use surveys confirm how much more time women spend doing childcare today compared to men. The unpaid labour of household and family management still largely falls on mothers, with dads “helping”, as homeschooling during COVID has laid bare.

Fathers interviewed in the late 1990s and early 2000s express a desire to be more involved, but are tied to paid work that limits the time and opportunity for parenting. Many speak of the stress of trying to meet expectations at work, as well as home, and some feel excluded from family life.

Peter, a man born in the mid-1950s in Victoria, recalls:

“I was probably working pretty long hours and a lot of the duties were left up to my wife to do […] Even on the weekends, I found that if the kids had a choice of who they would go with, they tend to choose my wife anyway. I found that distressing quite often.

“I never used to get home from work till 7-7.30. My job was to earn money, and the only time I did stuff around the house was on the weekend and for the kids.”

The fathers who spend the most time with their children tend to be those living in less typical family types, including single and stay-at-home dads.

Gay male couples with kids are less detached from their children’s daily care than fathers in heterosexual couple families, perhaps because they’re able to evade the “gender baggage” that influences men’s and women’s roles in families.

The parenting paradox

Today’s Australian fathers face a striking paradox. They’re expected to be more “hands-on dads”, yet there’s been little systemic change in their working lives (including access to, and uptake of, parental leave and flexible work). There’s also been little change to gendered roles in family arrangements – a situation that, admittedly, many fathers have been happy to roll with.

Most fathers are still working long hours, and many are concerned about how little time they have to be engaged fathers. Today’s dads may not view breadwinning as their raison d'être, but the breadwinner model of Australian fatherhood is not yet “history”.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.