With much of the country in lockdown, and many blaming the federal government for the botched vaccination rollout, support for the government is on the slide.

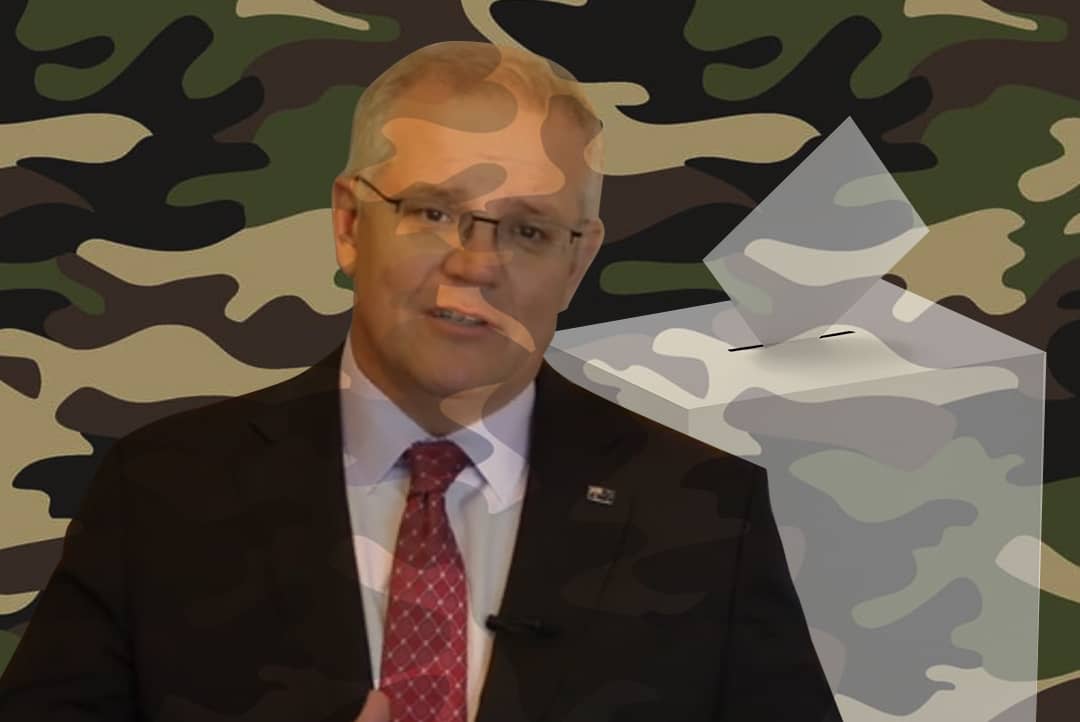

What’s the government’s plan to reverse the downward trend? Recent signs point to war/law and order as part of its strategy, with a solid chance it will run a khaki election.

A war/law and order strategy creates, amplifies or highlights a crime and/or military threat to fuel fear in order to gain political advantage.

A khaki election is one where war/law and order is the central campaign plank. The strategy typically includes the prime minister and other senior politicians closely aligning themselves with the police and military, including appearing with men in uniform, legislation that increases police, security agency and executive power, using war language, and creating a sense of emergency.

Khaki elections work best for incumbents and conservative governments. When people are fearful, changing government can feel risky. Khaki elections build fear of the “other”, and glorify traditionally male occupations of crime-fighting and war, and attributes such as being tough, resolute and hard. In the “us and them”, “with us or against us” mentality in which such campaigns thrive, political opposition is painted as “soft”.

While conservative governments favour privatisation of traditional government functions, they nevertheless support a “strong state” through support for the police and the military.

Copying the 2001 federal election playbook

The 2001 federal election is an emblematic example of a khaki election. It appeared that then prime minister John Howard would lose the election in October that year.

Liberal Party polling indicated that law and order was an effective way of appealing to people’s race-based anxieties with credible deniability.

This, and similar tactics used successfully by the Republicans in the US, informed the Liberal National Party's (LNP) election strategy. The arrival of the Tampa, a Norwegian ship carrying hundreds of mainly Afghan and Iraqi rescued asylum seekers, off Australia’s coast in August provided the perfect vessel to operationalise the strategy.

The military was used to repel the Tampa. The rescued asylum seekers were dubbed “illegal” and, in the wake of the September 2001 attacks on the US and the subsequent “war on terror”, terrorists.

Extraordinary legislation was passed to support the infamous “Pacific Solution” to detain asylum seekers offshore. The “tough on border protection” worked to reverse the LNP fortunes, and it won the election.

The 2001 federal election was a milestone. It was the first time a war/law and order campaign had been run at a federal level.

Previously, such campaigns were confined to the states, which constitutionally are responsible for crime.

The federal government’s ability to use the military escalated the sense of threat beyond crime to national security. It set a pattern. In the 2004 election, Howard’s successful strategy was “to attack Labor as weak and divided on national security, and in the war against terrorism”.

While khaki elections haven’t always delivered electoral success, they’re part of the LNP’s repertoire. The government’s COVID response, Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s “Operation Ironside” presser, and the recent increased emphasis on China as a threat, suggest that the LNP will look to war/law and order to lift its political fortunes.

The federal government has militarised its COVID response. It appointed Lieutenant General John Frewen in June as commander of the vaccine rollout, now dubbed Operation COVID Shield. The commander’s role is to communicate and increase public confidence in the vaccine rollout.

Announcing these developments, Morrison pointed to his “success” with the ADF-led Operation Sovereign Borders. Morrison has used the language of war to characterise the pandemic response, for example, declaring:

“[W]e are in a war against this virus, and all Australians are enlisted to do the right thing.”

Even the government’s vaccination slogan, “Arm yourself”, has a military flavour.

The government’s attempt to enlist COVID in the service of a war/law and order strategy, however, has proved challenging.

COVID is a health crisis. A successful war/law order strategy requires its proponents to control the narrative. Where a problem is framed as a national security issue, secrecy can be justified as necessary to protect the country, and the government can claim to be acting in line with the legally-protected confidential advice of security agencies.

Withholding information about the federal government’s COVID response is more difficult to justify and achieve. Medical experts regularly feature publicly as critics of the government’s COVID response, as do state premiers, the federal opposition, and union leaders representing frontline and essential workforces.

The public are able to form their own opinion based on direct experience of the vaccine rollout.

Finally, in a global health crisis, the federal government's performance can be benchmarked against other countries. Australia’s last position on the OECD’s table of the fully vaccinated is damning and oft quoted.

While the COVID threat has proved difficult to corral into a khaki framework, Morrison has jumped on other more promising issues.

He held a lengthy presser in early June to extol the success of Operation Ironside, a collaboration between the AFP and the FBI targeting international drug traffickers.

Read more: Encryption, crime-fighting, and the balancing act between community safety and individual privacy

The PM, alongside the Minister for Home Affairs, the AFP Commissioner and the FBI legal attaché, spoke about the success of the operation.

He said the operation had “struck a heavy blow against organised crime”, and that “everything we have been doing is to keep Australia safe”.

He also spoke of his “belief in law enforcement agencies”, and praised and thanked the thousands of police around Australia involved, extending his “great thanks and great respect”.

The PM explicitly politicised the presser by referring to legislation to increase security agency powers opposed by Labor.

Fighting organised crime and the “war on drugs” provide firm footing for a war/law and order strategy. The claimed details of the success of Operation Ironside, in saving lives and arresting dangerous criminals, cannot be readily independently assessed or critiqued.

Government praise for police work is difficult to criticise. By way of contrast, government praise of workers on the frontline of the pandemic, who are often low-paid, precarious, and female, risks drawing attention to government policies that fail to prioritise or support these workers.

The China factor

China looms as a possible vehicle for war/law and order politics. The government has highlighted China as a threat, and there’s increased public fear of China.

The extent to which the government will be able to segue this to political advantage is questionable. China is our biggest trading partner. Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce had a hard time wrestling this contradiction when questioned on the ABC’s Insiders earlier this month about his claim that China is our biggest security threat.

"I am worried that with the government behind in the polls they are gearing up for a khaki election."

WATCH: @AdamBandt on Peter Dutton's suggestion Australia should host more US marines in the Northern Territory #Insiders #auspol pic.twitter.com/wc8Qm0GDKZ— Insiders ABC (@InsidersABC) 12 June, 2021

Asked if this meant we would stop trading with China, he argued that we needed to keep trading with China to stay strong economically in order to counter the threat it posed.

The government’s slow vaccine rollout and its impact on people and the economy is taking its toll on its re-election chances. From now to the next election it will be looking to play catch-up on the vaccine rollout, and hone a winning narrative that fits ideologically.

Evidence is mounting that it will look towards a khaki election to camouflage its weaknesses and play to its strengths – though it’s not clear yet what, or who, the enemy will be.